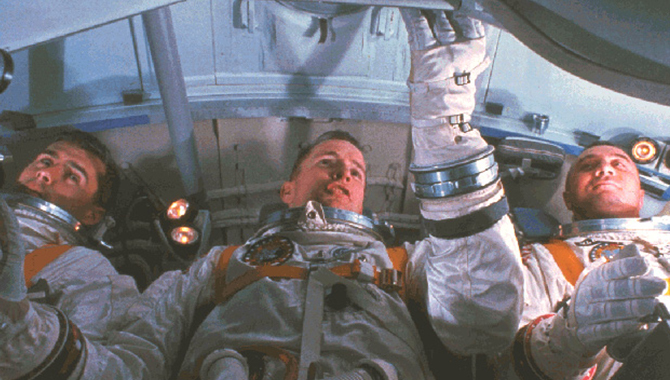

Close-up view of astronauts James A. McDivitt (foreground) and Edward H. White II inside their Gemini IV spacecraft.

Credit: NASA

Gemini IV astronauts solve hatch problems, test human endurance.

In 1964, NASA Astronaut James A. McDivitt interrupted a Saturday morning breakfast at the family’s long table in their Houston home. “Kids, I’m going to tell you something really important,” he began.

McDivitt had recently been selected as Command Pilot of Gemini IV, the second crewed flight of Project Gemini. The decision had been announced internally, at an astronaut pilots’ meeting, but a public announcement was still pending. “You know that dad’s an astronaut and the astronauts fly in space,” McDivitt recalled telling his children, in an oral history. “I just want to let you know that I’m going to fly in space soon.”

“And my older boy, Mike, who was probably seven or eight, says, ‘Oh yeah, dad, I heard that at school.’ And then my daughter Ann said, ‘Oh yeah, dad, I heard that at school, too.’ And my son Patrick said, ‘Dad, there’s a fly in the milk bottle.’”

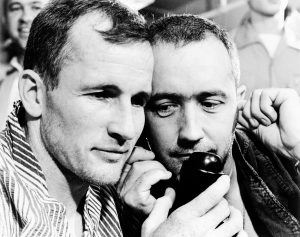

Astronauts Edward H. White II (left) and James A. McDivitt listen to the voice of President Lyndon B. Johnson on June 7, 1965, as he congratulated them by telephone on their successful Gemini IV mission.

Credit: NASA

Gemini IV launched from what is now Cape Canaveral Space Force Station on June 3, 1965. Edward H. White II served as Pilot for the mission. White and McDivitt were friends, having met in the late 1950s when both entered the University of Michigan to pursue degrees in aeronautical engineering.

“[Ed] was the best friend I ever had,” McDivitt recalled. “We lived … a block and a half or so apart on Saunders Crescent in Ann Arbor [Michigan]. He was getting a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering, but he didn’t have an aeronautical engineering undergraduate degree. So, we took a lot of classes together. We started flying together.”

White and McDivitt were members of NASA Astronaut Group 2, their selection announced on September 17, 1962. When they joined NASA, Project Mercury was winding down and Project Gemini was taking shape.

What Gemini IV is remembered for today—the first American spacewalk—was actually a late addition to the mission planning. The mission was primarily to serve as a test of human performance during what was then a long-duration flight. At approximately four days, the mission was about three times the duration of Mercury-Atlas 9, when L. Gordon Cooper spent more than 34 hours in space.

“And so, finally about two months or maybe even less [before the flight], we decided we’d actually do it [the spacewalk]. And so, we started working on all the things we needed,” McDivitt recalled. Opening and closing the hatch was added to an altitude chamber test. Near the end of that test, the spacecraft was depressurized and McDivitt and White, wearing their pressurized spacesuits, opened the hatch. When they closed it, they couldn’t lock it. Already more than 12 hours into the test, they completed it with the spacecraft depressurized and the hatch unlatched.

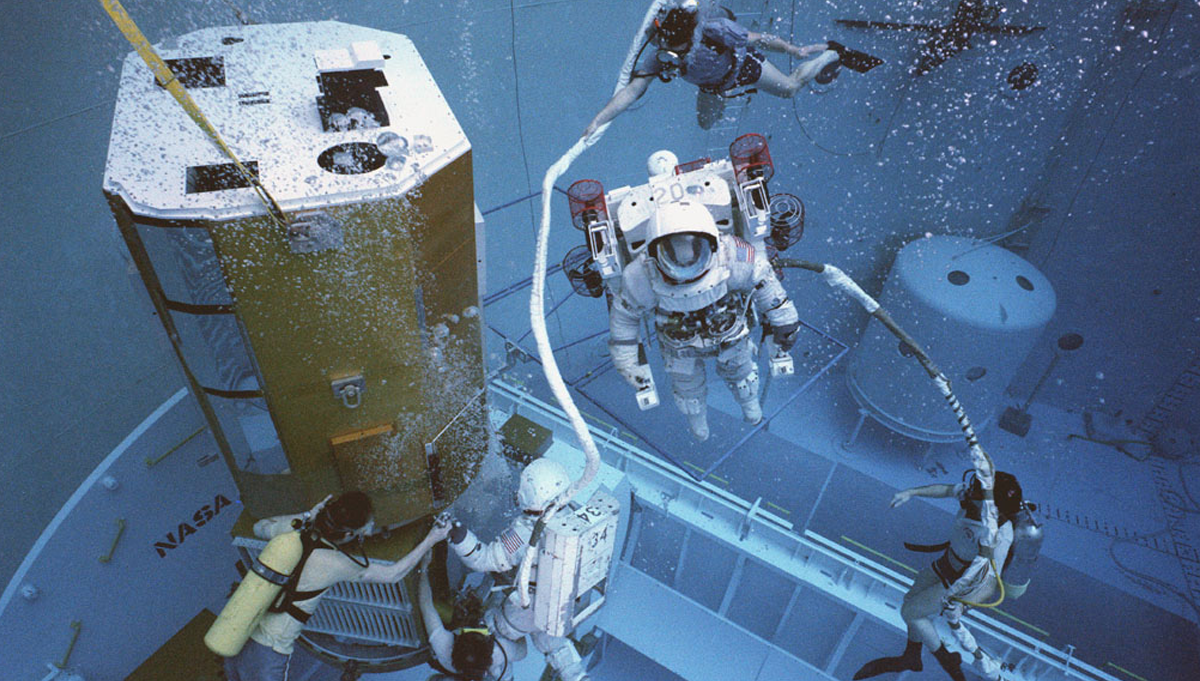

Astronaut Edward H. White II floats in the zero-gravity of space during the third revolution of the Gemini IV spacecraft.

Credit: NASA

Following a debriefing, McDivitt found an engineer working on the hatch to determine the cause of the problem and helped him examine the system of small gears that engaged and disengaged the handle. “… It was a fairly complex mechanism. … And those gears weren’t really going together properly. So, he did something to them and, you know, it worked. But fortunately, I saw what they look like,” McDivitt recalled.

“And then when we got around to doing the [Extra Vehicular Activity], … when Ed went to open up the hatch, it wouldn’t open. I said, ‘Oh my God,’ you know, ‘it’s not opening!’ And so, we chatted about that for a minute or two. And I said, ‘Well, I think I can get it closed if it won’t close.’ But I wasn’t too sure about it. I thought I could. But remember, then I would be pressurized. I wouldn’t be in my sports clothes, leaning over the top of the thing with a screwdriver. I’d be there pressurized. In the dark. So anyway, we elected to go ahead and open it up. And we didn’t bother telling the ground about that. I mean, there was nothing they could do.”

White exited the capsule during the third orbit, at about 3:45 p.m. ET on June 3, 1965. Tethered to the spacecraft, White used a small, hand-held device that emitted jets of oxygen to maneuver in space for the first three minutes, until the fuel ran out. For the final 20 minutes, White moved by pulling on the tether, which included his oxygen and communications lines, wrapped in gold tape.

“I feel like a million dollars,” White said. “This is the greatest experience. It’s just tremendous.”

“He was just having a ball out there,” McDivitt recalled. “He didn’t want to come back in. I wanted him to come back in because I didn’t want to have to work on that hatch in the dark. But, even if he’d have come back in when I told him to come back in, we would’ve still been working on the hatch in the dark…”

The Gemini IV spacecraft is hoisted aboard the recovery ship USS Wasp during recovery operations following the successful four-day mission.

Credit: NASA

“So, when we went to close the hatch, it wouldn’t close. It wouldn’t lock. And so, in the dark I was trying to fiddle around over on the side where I couldn’t see anything, trying to get my glove down in this little slot to push the gears together. And finally, we got that done and got it latched,” McDivitt recalled.

“I knew more about that hatch than probably anybody in the world, other than the technicians who’d built it. There wasn’t anybody in that Mission Control Center who knew anything about it, so there was no sense in me talking to them. Well, I made the decision to open it. And fortunately, I got it closed!” McDivitt said, later explaining, “…we would’ve never gotten to the Moon when we did if we’d taken baby steps all the way.”

McDivitt and White conducted 11 science experiments during the remainder of the mission, which included testing the potential of sextant navigation to aid Apollo lunar missions and using a 70-millimeter Hasselblad camera to photograph cloud patterns and the terrain of Earth.

Gemini IV returned to Earth on June 7, 1965, splashing down in the North Atlantic Ocean. Scientists would begin to have greater confidence in the human body to withstand prolonged space travel. McDivitt would go on to serve as Commander of Apollo 9, the first test of the Lunar Module in space. White was selected for the crew of the first piloted Apollo mission and lost his life in the Apollo 1 accident on January 27, 1967.

To learn more about Gemini IV and see video of the first American spacewalk, click here.