Apollo 9 crew, from left, James A. McDivitt, David R. Scott, and Russell L. Schweickart, posing in front of their Saturn V rocket at Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Pad 39A.

Credit: NASA

Mission validates the critical link to landing humans on the Moon and bringing them home safely.

The U.S. race to the Moon continued 50 years ago this month, with the launch of Apollo 9 on March 3, 1969. The mission came less than three months following the drama of Apollo 8, which orbited the Moon on Christmas Eve, 1968. But the engineering tests of Apollo 9 were no less critical to the future success of the Apollo program, proving the capability of the new Lunar Module (LM).

“Apollo 9 was an engineering mission from beginning to end. We tested every possible thing that could be tested. The mission was completely dedicated to testing the systems, the engines and guidance and navigation—all kinds of things that we could do in Earth orbit,” recalled Lunar Module Pilot Rusty Schweickart, in a NASA video.

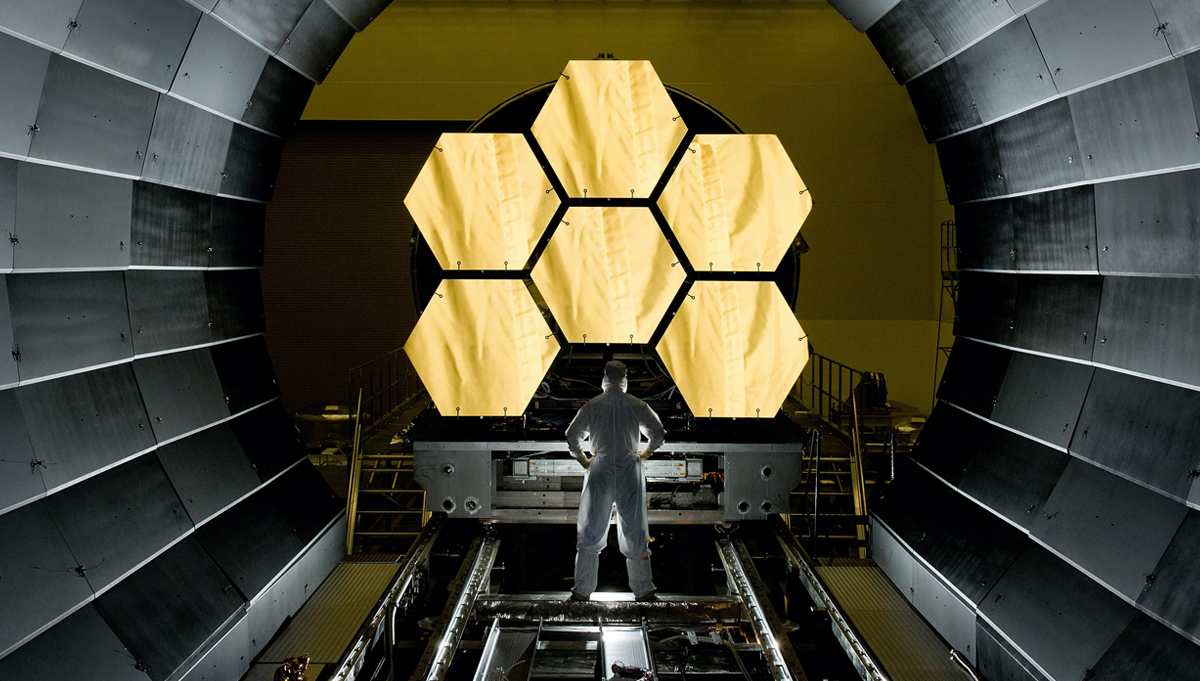

Lead Flight Director Gene Kranz (seated) and managers and controllers monitor the

Apollo 9 launch from Mission Control in Houston.

Credit: NASA

Because the LM would go on to perform flawlessly in space, it is perhaps easy to forget the significant engineering development challenges it posed for NASA and its contractors. No spacecraft before had been designed exclusively for outer space, where shielding requirements were greatly reduced, and weight reduction was paramount. Apollo 9 Commander James McDivitt recalled, in an oral history, his and Schweickart’s shocking first encounter with the LM during its development.

“We go over there, and we get in the spacecraft, and we crawl in. And I can remember the first thing we did is we knocked off the shield around the environmental control system, which was a thing about as thick as a piece of paper and made out of plastic,” McDivitt recalled, adding that during several hours of moving around the craft “…everything we touched fell off the wall or broke or it did something!”

Finally, McDivitt vehemently complained about the flimsy nature of the training vehicle, “and then I shut up, and there’s this long pause. And finally somebody comes on the intercom and says, ‘Jim, that is the flight vehicle.’ ”

Delays in development of the LM meant that Apollo 8 flew without one. Apollo 9 became the first crewed Apollo flight to include the new spacecraft. The LM had a mass of 33,500 pounds at launch and was equipped with both descent and ascent engines. It was 23 ft, 1 in. tall and 31 ft wide.

“Frankly, with the exception of the first lunar landing, I could not and would not pick any other mission,” said Schweickar, in an oral history. “I mean, the first flight of any vehicle is a test pilot’s dream.”

When the Apollo 9 lifted off, the LM was nestled inside the top of the final stage of the Saturn IVB rocket. Once the astronauts were in orbit, they released the Command Module from the SIVB, turned it 180 degrees, docked with the LM, and pulled it free. This maneuver was somewhat counter intuitive, McDivitt recalled.

“It’s really very difficult to get the coordinates system in your head,” McDivitt said. “Normally we dock looking out this way [ahead] and for the docking with the Lunar Module, you had to look up this way. So, the control system didn’t operate the way it normally would.”

A view of the Apollo 9 Lunar Module (LM) “Spider” in a lunar landing configuration, as photographed from the Command and Service Modules (CSM) on the fifth day of the Apollo 9 Earth-orbital mission.

Credit: NASA

Despite the awkwardness for the astronauts and an issue with several switches having been bumped into the wrong position during the flight, the docking was successful, proving the concept in space. The astronauts fired the Service Propulsion System (SPS) four times early in the mission to reposition the Command Module. The first two, both five seconds long, tested the performance of the LM under thrust and vibration. Having withstood those forces, the third burn was a much longer four minutes and forty-two seconds, which subjected the docked spacecrafts to forces they would experience during a lunar mission.

McDivitt and Schweickart moved via the tunnel into the LM and performed a series of tests, including firing the LM’s descent engine for more than six minutes, simulating a lunar landing. This descent engine could produce 10,125 lbf of thrust, using Aerozine 50 fuel and nitrogen tetroxide oxidizer. During the final 59 seconds, McDivitt varied the throttle from 10 to 40 percent as a Moon landing would require.

The technical highlight of the mission came on Day 5, when the LM, with McDivitt and Schweickart aboard, undocked from the Command Module and fired the descent engine to separate by 113 miles. The modules were apart for about 10 hours. During that time, McDivitt and Schweickart jettisoned the descent stage, which in later missions would be left on the surface of the Moon. The ascent engines were then fired to return the LM to the Command Module for docking.

During the mission, the astronauts performed an extravehicular activity (EVA) to test if the system of handrails on the exterior of the modules provided enough stability to enable astronauts to move safely between the two if the connecting tunnel was somehow unavailable. Command Module Pilot David Scott was filming Schweickart perform this walk through the open hatch, when the camera jammed.

The Apollo 9 spacecraft, with astronauts James A. McDivitt, David R. Scott, and Russell L. Schweickart aboard, approaches touchdown in the Atlantic recovery area.

Credit: NASA

“So, I just swung around while Dave was messing around with the camera, which he never did get fixed. I just spun around and I looked at the Earth…,” Schweickart recalled. “So that five minutes was a very special five minutes. I’m part-way up the front of the Lunar Module, making sure that I could safely do that and not poke holes in the suit with the antennas and things. And everything was quiet. Nobody was talking. That beautiful Earth out there. I mean, that’s when I really saw just the beauty of where I was.”

Apollo 9 splashed down in the North Atlantic on March 13, 1969. The engineering mission, that in hindsight is lost for some between Apollo 8 and Apollo 11, provided crucial testing and data about the LM and its performance capabilities.

“…I thought that lunar module was kind of the key to the whole thing,” McDivitt recalled. “If it worked, we had a chance. If it didn’t work, you know, we’d be at it for another two or three decades. … And, oh, it worked fine. And the fact that the rendezvous worked okay. The computers worked. The radar worked. … But we had to make sure that it went together well and that it would work, because it was really a flimsy little spacecraft.”

Following the mission, McDivitt moved into a position in the Apollo Program Management Office, where his hands-on testing of the LM during Apollo 9 informed decisions on how the LM could be used to help save the astronauts on Apollo 13 and bring them safely back to Earth after an oxygen tank exploded enroute to the Moon.