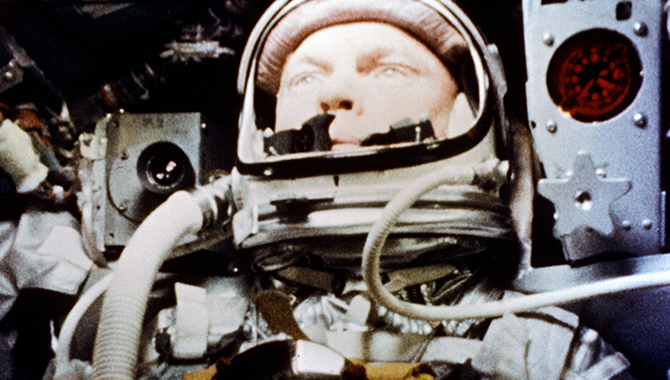

John H. Glenn Jr. during his historic flight in the tight Mercury spacecraft on February 20, 1962.

Credit: NASA

Astronaut demonstrated capability of humans in space, guiding the capsule manually for multiple orbits and an eventful reentry.

On February 20, 1962, 57 years ago this month, John H. Glenn Jr. was strapped into the Mercury spacecraft atop a powerful Atlas rocket, going through the launch countdown procedure. Again.

“The day I finally went, that was the third time I had actually suited up and been on top, been locked in and ready to go,” Glenn recalled decades later during a NASA interview. History awaited Glenn, who would become the third American in space and the first American to orbit the Earth, as the U.S. attempted to catch the Soviet Union’s space program, which had accomplished the feat in 1961.

This was the first manned mission coupling the Mercury capsule with the powerful Atlas rocket, which had been developed originally for weapons systems, with reliability far below the standards needed for human space flight. The rocket, which had taken years of refinement to reach acceptable reliability, stood nearly 95 ft tall, with a diameter of 10 ft, and produced more than 341,000 lbf of thrust.

Although Atlas would become the workhorse of the U.S. space program, it forced several launch delays on this mission, known as MA-6. The launch date was pushed back from January 16, 1962 because of an issue with the rocket’s fuel tanks. Following weather delays, the launch was further pushed back from February 1, after a leak during fueling soaked insulation on the rocket. On February 20, the rocket was ready and so was the weather.

Glenn recalled that as an astronaut on the verge of history, he didn’t have much time for philosophy on the launchpad. “When you finally get in the thing and you’re ready to go, you’re very, very busy. People think you’re in there contemplating great thoughts. But I think it’s more likely you’re in there, as I was, double-checking all the instrumentation, talking to the people on the ground crew to make sure that everything was okay to launch.”

The countdown was paused on February 20 so the ground crew could replace all 70 bolts that held the hatch in place, after they discovered that one of them was broken, and to repair a liquid oxygen propellant valve. The mission, dubbed Friendship 7, launched at 9:47 a.m.

The launch of the MA-6, Friendship 7, on February 20, 1962. Boosted by the Mercury-Atlas vehicle, a modified Atlas Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM), Friendship 7 was the first U.S. manned orbital flight and carried Astronaut John H. Glenn into orbit.

Credit: NASA

“People look at all this fire and smoke on the ground and think you’re under huge stress inside. You’re not,” Glenn explained. “The thrust is just barely greater than the weight of the spacecraft. So, you lift off very gently. And the more the fuel burns out, the lighter it becomes. And the thrust is still high. So, the farther you go up here on this entry into space, the more Gs you feel inside.”

Although, in hindsight, Mercury set the stage for Gemini, which set the stage for Apollo, there were still significant questions about human performance in space when Glenn blasted off in 1962. Would he be able to eat? Would he be able to focus his eyes?

The mission lasted four hours and 55 minutes, orbiting the Earth three times. By the time Glenn splashed down in the North Atlantic, about 800 miles north of Bermuda, many of the questions about human performance in space had been answered.

Glenn was called to fly the capsule manually, after a malfunctioning yaw attitude control jet forced him to turn off the automatic system guiding the flight. The flight had included a 30-minute test of manual flight, but the malfunction meant Glenn manually controlled the second and third orbits and re-entry.

More troublesome was an indication from the heat shield circuit that a clamp had released and the shield was loose. The ablative shield was designed to dissipate the 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit reentry temperatures. A loose shield might have caused the Mercury capsule to incinerate during reentry.

“I certainly wanted to make it a two-way trip and come back, of course,” Glenn recalled. It was decided to keep the retropack on the bottom of the capsule, although it was designed to be jettisoned. The retropack, it was thought, would help hold the heatshield in place.

“While the reentry was going to be interesting anyway, … it was even more interesting because as I would glance occasionally out the little window, I could see chunks of that retropack breaking up and coming back by the window,” Glenn said. “I couldn’t be absolutely certain then whether it was the heat shield breaking up or the retropack. Obviously, it was the retropack or I wouldn’t be here today.”

About 60 million people watched the launch of MA-6 on live television. Glenn returned a hero, addressing a joint session of Congress and riding in ticker-tape parades in his honor. The mission’s success in closing the gap with the Soviet Union, and Glenn’s calm under pressure when things went wrong, set the stage for NASA’s many successes to come.