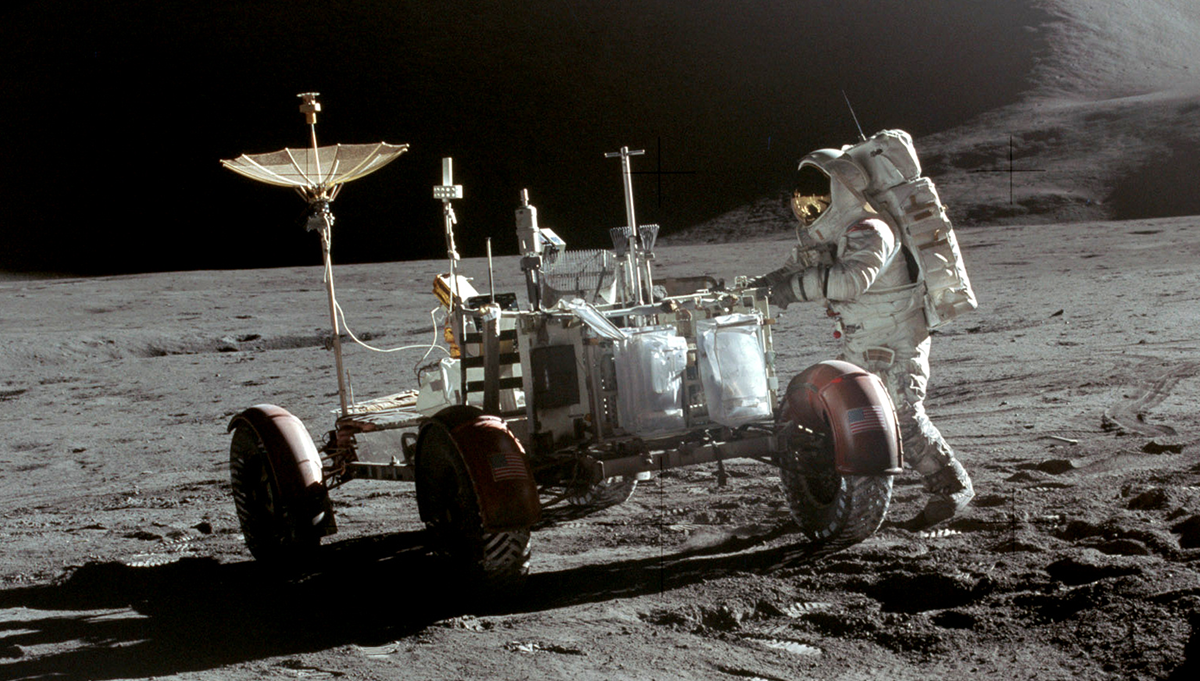

Astronauts John Grunsfeld and Andrew Feustel perform the first of five spacewalks scheduled on STS-125 to upgrade and extend the working life of the Hubble Space Telescope. Photo Credit: NASA

The crew of STS-125 make repairs and upgrades to the revolutionary telescope, expanding its capabilities and extending its operational lifespan.

On May 12, 2009, NASA astronaut Scott D. Altman alerted Mission Control that the crew of STS-125 could see a star approaching from the East. This was terrific news, Mission Control responded.

“We hope to get a lot closer,” Altman added with a chuckle.

Altman had already rendezvoused with the “star” once before, in 2002. Now he was leading what would be the final crew to ever visit the Hubble Space Telescope. STS-125 was an ambitious mission to improve upon Hubble’s already impressive capabilities and extend how long it could continue to operate.

“When I was on the flight deck rendezvousing with Hubble, I felt like it was very crowded,” Altman would later explain during an APPEL Knowledge Services VPMC. “There were so many people who had worked so hard to get us to that point. It wasn’t just the six other crew members.” There was mission control, the trainers, the scientists and engineers who developed the instruments, the personnel at Kennedy Space Center who maintained the space shuttles and got them ready to launch.

STS-125 crew members pose for a portrait in front of an American flag on Atlantis’ middeck. From left to right, back row: Mission Specialists Michael Good; Mike Massimino, John Grunsfeld, Andrew Feustel. From left to right, front row: STS-125 Pilot Gregory C. Johnson, STS-125 Commander Scott Altman, and Mission Specialist Megan McArthur. Photo Credit: NASA

“It was a total team effort,” Altman said. “The other part of teamwork, though, is to understand the ability to let people do their jobs, and not try to do it for them, and to use those people to create a cohesive whole in the end. If you don’t have all those people working in sync, in the end, you’re not going to accomplish the goals you set out to.”

Of the crew, Altman and Mission Specialists John M. Grunsfeld and Mike Massimino were veterans of STS-109, the previous Hubble Servicing Mission. Pilot Gregory C. Johnson and Mission Specialists Michael T. Good, Megan McArthur, and Andrew J. Feustel were making their first spaceflights.

The goals for STS-125 were lofty. Foremost was replacing the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 with the $132 million Wide Field Camera 3, which was scheduled to be the first action of the first spacewalk. The sophisticated new instrument would give Hubble the ability to capture the ultraviolet and infrared spectrums as well as visible light in staggering detail, helping scientists better understand the formation of stars within galaxies.

On May 14, Grunsfeld and Feustel exited the hatch of the Space Shuttle Atlantis, with Hubble towering over them in the payload bay. The spacewalk to replace the camera quickly reached an impasse when Feustel discovered that a bolt holding the camera’s grounding strap in place could not be loosened using the approved procedure.

“What we found is on the ground, it’s hard to imagine everything that can go wrong in space, and we ran into situations nearly every day where something was not what we expected,” Altman said. To get beyond those situations often requires teamwork, communication, and imagination.

Astronaut John Grunsfeld, STS-125 mission specialist, works with a power tool on the middeck of Space Shuttle Atlantis as he prepares for upcoming spacewalks to repair the Hubble Space Telescope. Photo Credit: NASA

The crew had thought that the bolt might be stuck. It had been in space since 1993, after all. But bringing out a new torque limiting wrench and working up from 42 ft-lbs. to 45 ft-lbs. and finally to the maximum 48 ft-lbs. didn’t free the bolt.

“Now we don’t have any more contingency procedures,” Altman recalled. “All we have is basically a breaker bar with no torque limit on it.” Mission Specialist Mike Massimino clarified with Mission Control that at this point Feustel was cleared to use as much strength as necessary to free the bolt.

The stakes of this maneuver, which was the only option left, weren’t lost on the crew. By this point in his career, Grunsfeld, an astronomer with a Ph.D. in physics, was known in the astronaut corps as the “Hubble Repairman.” He was making his third trip to the telescope and was the lead spacewalker for the mission.

“When I went up to the Hubble Space Telescope with the teams that I’ve led, there has always been Rule Number 1,” Grunsfeld recalled in an ESA video. “Rule Number 1 is: ‘Don’t break the telescope.’ We’re in big, bulky space suits. And, after all, it’s a delicate, scientific instrument.”

Years later, Altman recalled waiting inside Atlantis as Feustel slipped the wrench onto the bolt and applied pressure. “If the bolt breaks, that camera is stuck in there forever and we’ve failed on our first task of the mission.”

“OK. Here we go,” Feustel reported, turning the wrench, which was followed by unsettling popping on the communications channel. And then, “I think I got it. It turned. It definitely turned.”

An STS-125 crew member onboard the Space Shuttle Atlantis snapped a still photo of the Hubble Space Telescope following grapple of the giant observatory by the shuttle’s Canadian-built remote manipulator system. Photo Credit: NASA

Over five spacewalks totaling 36 hours and 56 minutes, the crew of STS-125 successfully worked through a long list of repairs and additions to Hubble that included the Wide Field Camera 3, installing the new Cosmic Origins Spectrograph to study the early Universe, replacing the telescope’s Fine Guidance Sensors, replacing a 460-pound battery module, installing six new gyroscopes, and adding a new outer blanket for improved insulation.

“As an astronaut, the Hubble Space Telescope mission is kind of the holy grail of being able to go up and do something that is widely regarded as extremely important,” Grunsfeld explained. “I think the crowning achievement of all of our missions has been on the mission in 2009. This was technically the hardest, but I think also the most rewarding.”

To learn more about STS-125 and all 135 space shuttle missions, please visit APPEL Knowledge Services’ Shuttle Era Resources page.