NASA recently retired its DC-8 Airborne Science platform after more than three decades of research. The aircraft is shown here against the background of a dark blue sky on February 20, 1998.

Photo Credit: NASA/Carla Thomas

After more than three decades of amazing contributions to science, storied aircraft heads to Idaho for a new chapter.

On May 15, 2024, a sleek jetliner, landing gear engaged, banked in the skies above Moffett Federal Airfield. As NASA’s DC-8-72 began descending to the runway that day, it wouldn’t have been obvious to people looking up in nearby Mountain View, California that this was the end of an era.

The DC-8 aligned with runway 14R/32L one last time and sailed above it, never touching down. As the end of the runway approached, the pilot began pulling up and banked over San Francisco Bay, the plane cutting a sharp silhouette against the bright sky as the crew headed to Idaho.

NASA’s DC-8 Airborne Laboratory during a flight over the snow-covered Sierra Nevada Mountains. Photo Credit: NASA/Jim Ross

The aircraft was built by McDonnell Douglas in 1969 as a commercial passenger jetliner. NASA acquired it in 1985, transforming it into a flying laboratory equipped with state-of-the-art sensors and data systems, including Iridium and Inmarsat satellite communications capabilities. Based at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in California, the aircraft supported 158 research campaigns.

From 2016 through 2018, for instance, 42 scientists used a suite of 20 instruments aboard the DC-8 to measure the concentration of airborne aerosols and the levels of more than 200 gases in NASA’s Atmospheric Tomography (ATom) mission. During a series of sweeping journeys—each taking about 26 days—the DC-8 flew over the North Pole, the Pacific Ocean, New Zealand, the tip of South America, the Atlantic Ocean, and Greenland. It was the first mission to survey the atmosphere over the oceans this way, providing a rich, comprehensive dataset that produced more than 65 publications.

In the 11 years from 2009 to 2019, the DC-8 was equipped with lasers, ice-penetrating radar, and a gravity meter for a series of six-week missions to monitor polar ice levels in Antarctica, the Arctic, and Alaska, substituting for a satellite with failing lasers. The missions, Operation Ice Bridge, covered the years until NASA could launch a state-of-the-art replacement, the Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite-2.

Operation Ice Bridge required exacting flying skills. The flights not only replaced the satellite data, but they also helped the team “see” beneath the mile-thick sheet of ice in Antarctica to find evidence of the lakes, rivers, and valleys that were carved below by ancient glaciers and then covered 14 million years ago.

NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center flies the DC-8 airborne science laboratory in support of the Convective Processes Experiment – Aerosols and Winds campaign, CPEX-AW, on Aug 6, 2021. From left to right: Nils Larson, David Fedors and Mark Crane. Photo Credit: NASA/Carla Thomas

“The science instrumentation required that we fly from 500 feet to 1,000 feet altitude,” recalled retired NASA pilot Bill Brockett, who flew the DC-8 during the missions. “It required total focus for the 6 or 7 hours, at low altitude, to successfully complete a mission. The scenery was spectacular, and every mission was immensely satisfying to me. We were low enough that we occasionally got glimpses of seals lounging on the ice!”

“I always felt this airplane was tailor made for the kinds of work that NASA wanted to do with it,” Brockett said, in a NASA press release. “There is no other big airplane that I am aware of that has the failsafe redundancy that this airplane has. I felt very safe if we were flying around storms and there was turbulence.”

The Douglas Aircraft Company began developing the DC-8 in 1952, at first working to create an aerial refueling tanker for the U.S. Air Force. By 1955, it had evolved into a commercial airliner project. The aircraft flew for the first time in May of 1958. In 1961, as airlines were building fleets of DC-8s and the rival Boeing 707s, pilot William Magruder took a DC-8 test plane to a record altitude of 52,000 feet and then pushed it into a dive. At about 45,000 feet, the plane broke the sound barrier for 16 seconds. The flight, which tested a new wing edge design, set records for commercial airliners that stood for a decade. The DC-8-72 was designed in the 1960s to include several key advances, including quieter, more powerful turbofan engines. It has the capability to fly at a wide range of altitudes for as many as 12 straight hours.

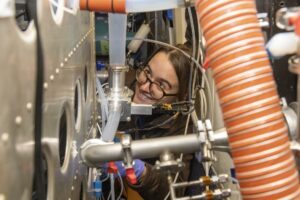

Kat Ball, Chemical Engineering Ph.D candidate at Caltech, attends to the Chemical Ionization Mass Spectrometer (CIMS) rack onboard the DC-8 aircraft at Building 703 in Palmdale, CA. The DC-8 aircraft was prepared for its last mission, ASIA-AQ (Airborne and Satellite Investigation of Asian Air Quality). Photo Credit: NASA/Steve Freeman

The final science mission for NASA’s DC-8 was the Airborne and Satellite Investigation of Asian Air Quality (ASIA-AQ) mission. ASIA-AQ provided data to help integrate the hourly observations from a new generation of air quality monitoring satellites with the corresponding data from ground monitoring stations and traditional satellites.

During the mission, one of the DC-8’s engines failed. The team, many of whom have worked with the plane for more than a decade, sprang into action to save the campaign.

“The logistics and procurement teams acted quickly to get the engine shipped and the crew was able to get the engine replaced, tested and ready to go. That could have been the end of the campaign, but our team made it happen,” said Brian Hobbs, NASA Armstrong DC-8 manager. “The comradery and the can-do attitude are impressive.”

The plane’s final NASA flight, which followed the flyover of Moffett, was to Pocatello Regional Airport, seven miles outside of Pocatello, Idaho. The federal government has donated the plane to Idaho State University, where it will become part of the college’s Aircraft Maintenance Technology Program, helping a new generation of airplane technicians gain hands-on experience.

NASA has acquired a Boeing 777-200ER to replace the DC-8. NASA’s Langley Research Center is modifying the plane with instrument ports, upgraded power system, data and communications systems, and internal modifications to accommodate science teams working to answer some of the most challenging questions in earth science.