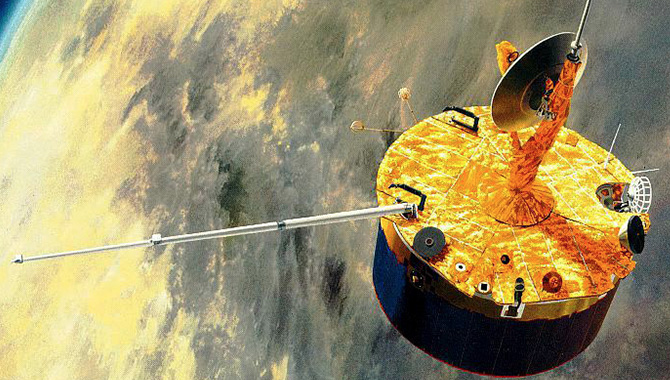

Engineers prepare Mariner 2 for flight. Credits: NASA/JPL

Team met technical challenges to gather first data from another planet.

In the early morning of August 22, 1962, a team of engineers and scientists watched in suspense as an Atlas-Agena rocket lit the night sky around Cape Canaveral, Florida. Atop the 118-foot-tall rocket was Mariner 2, a small spacecraft bound, audaciously, for Venus.

This early in the space age, successful launches were not a foregone conclusion. Just a month earlier, on July 22, a similar rocket carrying Mariner 1 lifted off seamlessly only to begin fishtailing and veering off course minutes into the flight. Concerned that the rocket could come thundering down into Atlantic shipping lanes, NASA issued a self-destruct code.

An investigation concluded that the failure stemmed from two issues. The rocket’s airborne beacon equipment became inoperative four times during the flight, intermittently losing rate signals. The longest instance was 61 seconds. This was compounded by a coding error in which handwritten equations were translated into computer code without a superscript overbar. This led to incorrect computation of guidance signals, causing the rocket to make a series of unnecessary, erroneous flight path adjustments and veer off course.

With the problems repaired well in advance of Mariner 2’s launch, leaders at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which was managing the Mariner program, spent weeks emphasizing to the public how difficult and complex it would be to send Mariner 2 to Venus.

“Now, obviously this is a high-risk mission. Even if the Mariner launch is completely successful, we have many critical flight problems to face,” said Bob Parks, JPL’s Director of Planetary Programs at the time, in a NASA video. “When the numbers came out and we analyzed them, there was a 1 percent chance of success in a sense that all of these components would work.”

Owing to development delays with the Atlas-Centaur rocket, Mariner 1 and Mariner 2 were streamlined to launch atop a smaller, less powerful rocket. The spacecraft employed a modified version of the smaller bus used in the Ranger program, which sent a series of spacecraft equipped with cameras to the Moon between 1962 and 1965.

Mariner 2 was built on a hexagonal base about 3.4 feet across. The probe weighed 447 pounds at launch, including 146 pounds of electronics, solar panels weighing 48 pounds, and a 77-pound structure. In space, with the solar panels unfolded, the spacecraft spanned 16.5 feet and was nearly 12 feet tall. It carried a suite of scientific instruments, including a microwave radiometer, an infrared radiometer, a micrometeorite sensor, a solar plasma sensor, a charged particle sensor, and a magnetometer. These instruments were designed to measure the temperature distribution on Venus’s surface and gather basic data about its atmosphere and magnetic field.

Mariner 2, the first successful interplanetary mission, returned reams of data about “Earth’s twin.” Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

By 1962, scientists had determined much about the orbital characteristics of Venus, but the planet’s surface remained a mystery. They knew Venus appeared to be covered by thick clouds that even the most powerful telescopes and radio observations could not penetrate. Earth-based observations were open to interpretation. Some scientists inferred that Venus’s surface might be extremely hot—possibly around 620° Fahrenheit. Others speculated the cloud tops might be about 220° Fahrenheit, shielding a more temperate surface.

For the team to learn more, Mariner 2 had to survive the nearly four-month journey to Venus. Challenges began almost immediately with the sensor that oriented the probe to Earth, so it could receive commands from the team.

“When we first turned it on up there, locked on the Earth, it was working fine,” Parks recalled. “But it was working at a much lower level of sensitivity than we had designed into it. As we got farther and farther away from Earth, we knew that if the sensitivity stayed [at that level], we wouldn’t be able to stay locked on the Earth all the way to the planet Venus.”

Luckily, just a few days before the team would’ve stopped being able to track Mariner 2, the signal strength increased to design levels. Soon after, Mariner 2 briefly lost attitude control, likely caused by a collision with a small object. The gyroscopes regained control after about three minutes.

On Halloween, the output from one of the solar panels dropped suddenly, prompting the team to turn off the instruments that were gathering data during the flight to Venus. About a week later, when the solar panel’s output returned to design levels, the team reactivated the instruments. On November 15, the solar panel failed permanently, but by then Mariner 2 was close enough to the Sun that a single panel could power the spacecraft.

Mariner 2 reached Venus on December 14, 1962, 62 years ago this month. With the full suite of instruments working, the spacecraft came within 21,000 miles of the planet’s surface. Any hope that Venus was Earth’s twin vanished. The data indicated that Venus was rotating slowly retrograde, with a carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere trapping heat beneath thick, continuous clouds. The data indicated surface temperatures reaching 459° Fahrenheit.

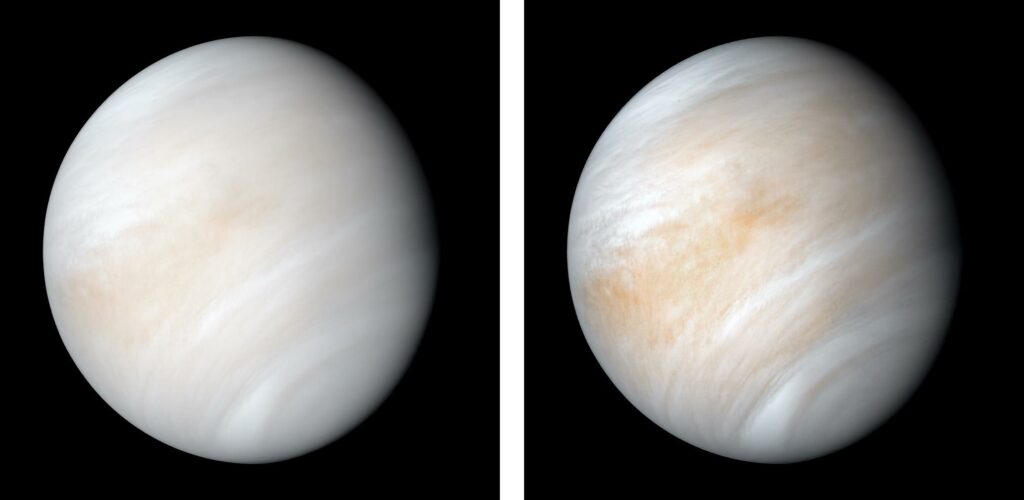

The Mariner 10 spacecraft captured this seemingly peaceful view of a planet the size of Earth, wrapped in a dense, global cloud layer. But, contrary to its serene appearance, the clouded globe of Venus is a world of intense heat, crushing atmospheric pressure and clouds of corrosive acid. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

“There will be other missions to Venus, but there will never be another first mission to Venus,” said Jack N. James, Mariner 2 project manager at JPL.

Mariner 2 was the first spacecraft to successfully encounter another planet. NASA would return to Venus with Mariner 5 in 1967, and again with Mariner 10 in 1974, learning more about the planet’s harsh, churning atmosphere and weak magnetic field.

To learn more about NASA’s Mariner program, click here.