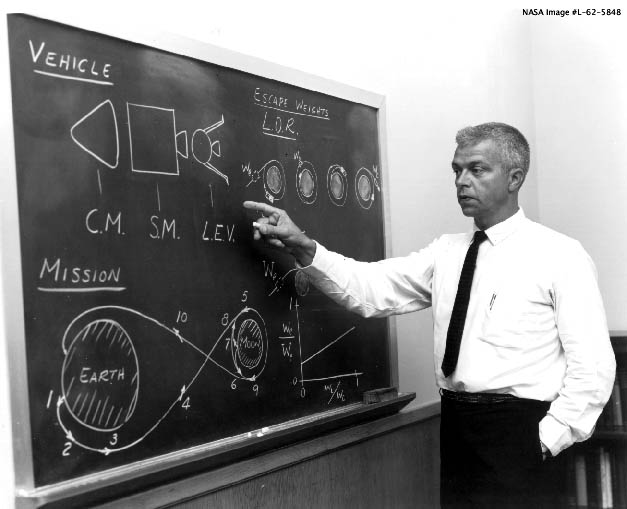

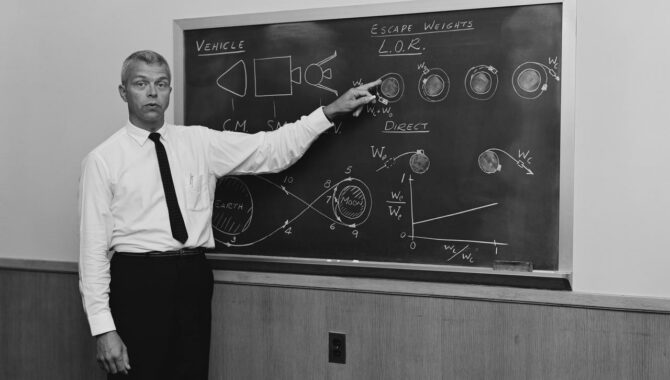

NASA aerospace engineer John Houbolt explains Lunar Orbital Rendezvous at a blackboard that illustrates the escape weights of the proposal. Credit: NASA

Understanding how pressure impacts performance can yield better decisions.

Beginning in late 1960, aerospace engineer John C. Houbolt found himself in a series of difficult conversations — intense, high-stakes meetings where he was called upon to explain a radical idea: that the United States could reach the Moon in under nine years using a technique called Lunar Orbit Rendezvous, or LOR. Houbolt was working at NASA’s Langley Research Center, a crucial hub of activity in America’s race to the Moon. He was convinced that LOR offered the best solution to the key technical challenges of Apollo.

But LOR was just one of three competing mission architectures under review as NASA began to sketch out the infrastructure it would need to reach and explore the Moon. And Houbolt’s idea faced formidable opposition. Influential leaders had already lined up behind the other two options: Direct Ascent and Earth Orbit Rendezvous.

Each option had drawbacks. For LOR, it was unclear if two capsules could rendezvous in space. And if that maneuver failed at the Moon, the consequences would be tragic. But LOR offered a clear advantage. A spacecraft designed only to orbit and land on the Moon could be much lighter. This meant NASA could achieve its mission goals while launching a much smaller rocket.

Houbolt presented the LOR concept to a series of panels. The pressure was immense. And although he was received professionally in the rooms, in reports following the meeting, LOR was derided as a “scheme.”

Outside those meetings, scientists were beginning to better understand what happens to a human being when they walk into a room to explain a complicated solution to an audience that already disagrees. The study of human performance under pressure would evolve while, and in some ways be informed by, what NASA learned during the next decade as the agency trained astronauts for spaceflight and coordinated the complex engineering efforts that sent the first spacecraft beyond Earth.

It became increasingly clear that success hinges not only on technical expertise, but also on the ability to understand what is happening during difficult conversations — moments of disagreement, doubt, or dissent that raise stress levels.

A comprehensive review of stress, cognition, and human performance conducted by NASA reveals that during moments of stress, attention narrows or tunnels, causing a person to reduce their focus on peripheral information and tasks. “What determines a main task from a peripheral task appears to depend on whichever stimulus is perceived to be of greatest importance to the individual or that which is perceived as most salient,” the author notes.

Stress also impacts individual judgment and decision making. Some researchers believe this could be the sum of earlier impacts on attention, memory, and appraisal. Others believe they represent a separate effect. Either way, “in general, judgment and decision making under stress tend to become more rigid with fewer alternatives scanned and considered. Furthermore, individuals under stress tend to favor revisiting past responses to a situation, even if those methods or problem-solving strategies hadn’t proven especially helpful.

NASA’s own experience underscores this. In the simulator, in the cockpit, in the control room, the agency learned that peak performance depends not just on expertise, but on how people communicate under stress. And that, in turn, depends on whether they feel safe to speak, to disagree, and to be wrong. The science of human performance has since confirmed what people like John Houbolt learned the hard way — even the best ideas can be lost if they’re not delivered — and received — with clarity, courage, and care.

Houbolt was in Mission Control in Houston on July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong stepped onto the Moon. Using Lunar Orbit Rendezvous, NASA reached the Moon with months to spare. Years later, Houbolt recalled that Wernher von Braun, Director of Marshall Space Flight Center and an early skeptic of LOR, turned to him and said, “Thank you, John. It is a good idea.”

To learn more about program and project managers can stay connected with their teams, minimizing stress, and fostering open feedback, click here.