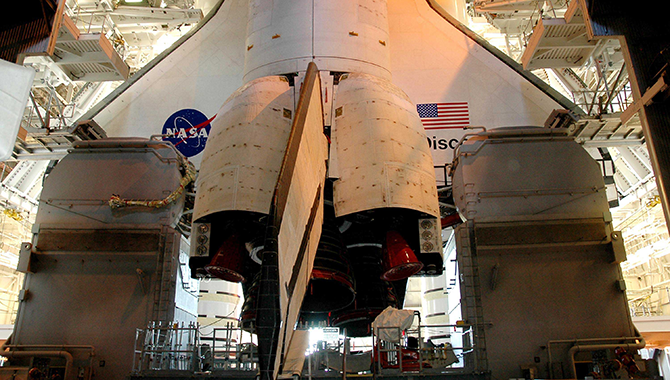

Space Shuttle Discovery in the Vehicle Assembly Building. On either side of Discovery’s tail and Orbiter Maneuvering System Pods are the Tail Masts that support the fluid, gas and electrical requirements of the orbiter’s liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen aft T-0 umbilicals.

Photo Credit: NASA/KSC

At Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Equipment Test Facility, I learned the hard way that supposedly bulletproof designs are not necessarily as trouble-free as they may appear.

The lesson I took away from the experience is this: no matter how simple and straightforward an engineering solution appears to be, don’t assume nothing can go wrong.

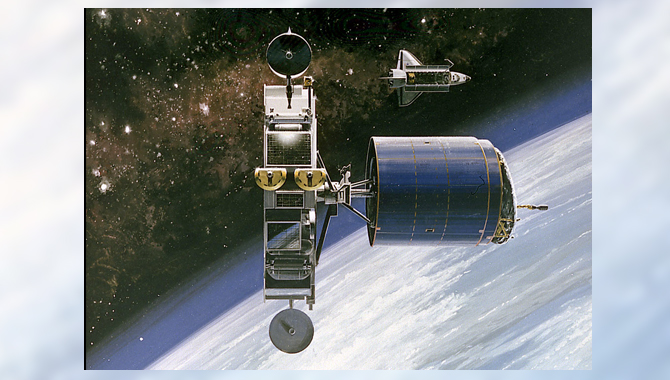

We were testing T-0 umbilicals. The umbilical is a two-piece interface between the ground and the orbiter, a large plate with specialized disconnects for many fluid, electrical, and communications systems. T-0 (“T minus zero”) describes its critical nature. The umbilical is designed to separate from the shuttle at an exactly specified moment when the vehicle begins its ascent.

The umbilical system release is activated by a drop weight. As the weight falls, it retracts the ground half of the umbilical away from the vehicle into the protective housing of the tall service mast by means of cables (called lanyards) attached to the umbilical plate. A set of slightly longer lanyards releases a door called a “bonnet” that falls over the opening in the mast, protecting the systems from the rocket exhaust that passes just a few feet away. Because that second set of lanyards is longer, the bonnet falls just after the umbilical is retracted into the housing.

Well, we knew for a fact that gravity works reliably twenty-four hours a day. And we had already tested the system successfully for Mobile Launch Platforms 1 and 2. When you release the weight, the chances are excellent that it will fall and take the lanyards and the umbilical with it. What could go wrong?

Since the system is critical and the timing of its operation had to be exactly coordinated with vehicle ascent, both sets of lanyards had turnbuckles that could be used to adjust their length. There is a lot of equipment in the tall service mast, including brackets for limit switches. (In those times, we used fairly primitive on-off switches that had to make physical contact with a surface—not like today’s touchless laser or ultrasonic devices.) During our test’s flight countdown procedure, the turnbuckle of the bonnet lanyard got snagged under a limit switch bracket, making it effectively shorter. That obviously affected the timing of the bonnet release. The bonnet fell just a tiny bit early—and smashed the umbilical before it was safely inside the mast’s protective housing.

Not surprisingly, damage to the umbilical was extensive. We had to return it to Rockwell Downey for repairs, and we did not see it again for many months.

The main lessons I learned from this unhappy experience are these:

- Make sure your test procedure is detailed enough to verify test configuration

- Work with design to simplify systems as much as practical

Since then, whenever I write or review a statement of work for design or special conditions for construction, I take a very close look at test requirements. There is no such thing as an absolutely failure-proof design, so whenever someone mentions testing, the thought that I share with you now automatically pops into my mind: If you plan to do a test, be prepared for the test to fail.

If you never fail, you may be paying too much attention to the little legalistic voice that whispers, “Play it safe.” We who work for NASA owe it to ourselves (and the taxpayers) to keep on experimenting, to keep on testing. That is “exploration,” which always involves failure.

So, let’s keep on testing. And when you do your next test, be ready for that test to fail.

Gene Hajdaj is a Construction Manager and Contracting Officer’s Representative at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center.

Read more articles in the “My Best Mistake”series.