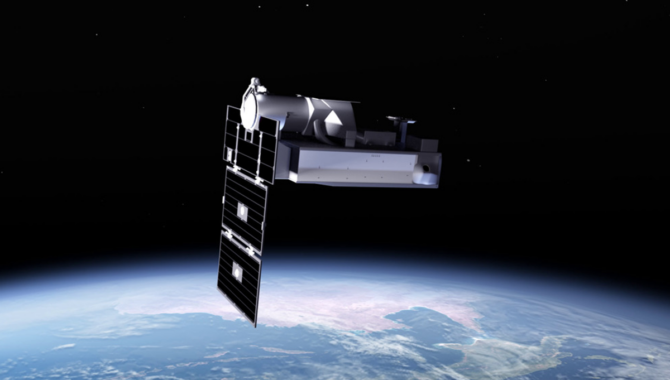

Artist's concept of the PUNCH Narrow Field Imager, or NFI instrument, from low Earth orbit. The NFI is designed to capture high-resolution images of the Sun's corona. Credit: NASA’s Conceptual Image Lab/Kim Dongjae, Walt Feimer

Four satellites will work together to create detailed images of the Sun’s corona seeking insight into how the solar wind forms.

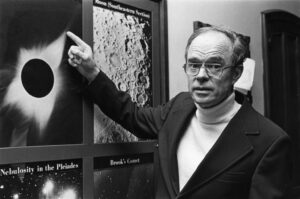

In 1957, a young astrophysicist working as an assistant professor at the Enrico Fermi Institute at The University of Chicago turned his attention to the mathematics of the Sun’s corona. Scientists had known for decades that the temperature of the Sun’s atmosphere must surely exceed 1 million degrees Fahrenheit. What Eugene Parker found in his calculations would dramatically change scientific understanding of the Sun and give rise to modern heliophysics.

Parker’s research indicated that the intense heat of the corona is so powerful that it enables particles to escape the Sun’s formidable gravity and flow through the solar system at supersonic speeds. He would later call the phenomenon the “solar wind” and it answered several puzzling questions from earlier researchers, including why the tails of comets always point away from the Sun.

Eugene Parker in 1977 pointing at an image of a total solar eclipse revealing solar wind features. Credit: University of Chicago

The idea faced fierce opposition at the time. When Parker submitted a paper to the Astrophysical Journal, reviewers dismissed his findings as “nonsense” and suggested he visit the library to do more research before writing on the topic. The journal’s editor, astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, didn’t embrace the concept of solar wind either, but he couldn’t find an error in Parker’s math, and published the paper.

“I have never made a significant proposal but what there was a crowd who said, ‘Ain’t so, can’t possibly be,” Parker told the University of Chicago in 2018. “If you do something new or innovative, expect trouble.”

But Parker wouldn’t have to wait long for validation. In 1962, NASA’s Mariner II spacecraft, on its way to Venus, gathered data that confirmed the Sun is indeed emitting a constant flow of particles. Decades later, astrophysicists know a great deal more about the solar wind, but fundamental questions remain.

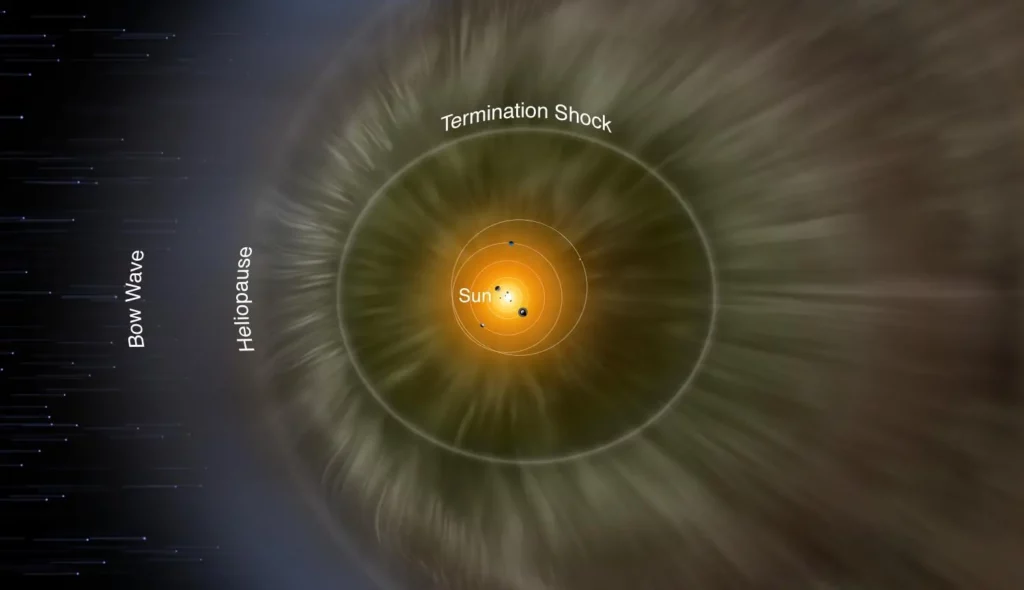

The Sun’s core is about 27 million degrees Fahrenheit. The visible surface of the Sun, the photosphere, is much cooler—about 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit. One of the biggest question scientists have is why, then, is the Sun’s outer atmosphere, the corona, as much as 3.5 million degrees Fahrenheit?

Every day, the Sun sends more than 300,000 tons of material outward into space, where it has profound impacts on the solar system. NASA measurements indicate the solar wind travels at least 161 miles per second—nearly 580,000 miles per hour—and sometimes much faster. Higher concentrations of helium correlate with the fastest speeds, which average about 1 million miles per hour.

Understanding more about the solar wind is important as NASA works to establish long-term human missions that will send astronauts into the dynamic space environment beyond the protections of Earth. On March 11, 2025, NASA launched a mission to study the Sun’s corona and how it transitions into the solar wind.

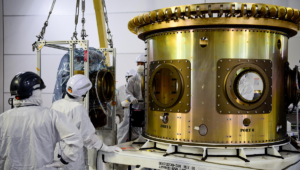

The mission is known as PUNCH, an acronym for the Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere. Four suitcase-sized satellites will operate in low Earth orbit, synchronized to operate as a single unit, developing a three-dimensional view of the Sun’s corona and the inner solar system.

“The Sun is never quiet,” said Nicholeen Viall, PUNCH mission scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, speaking at a recent NASA press conference. “The way that the Sun makes the corona and makes the solar wind, it’s constantly having little explosions. So, even when there’s not a big space weather event …, there’s still little events that constantly bombard our Earth.”

Technicians integrate NASA’s four PUNCH satellites to the evolved expendable launch vehicle secondary payload adapter array ring inside the Astrotech Space Operations Facility at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California on Friday, Feb. 14, 2025. Credit: USSF 30th Space Wing/Joe Davila

Four satellites enable PUNCH to develop a continuous, comprehensive view of the full inner solar system. Each satellite is approximately 1 ft x 2 ft x 3 ft and weighed about 140 pounds on Earth. They operate in concert to develop a three-dimensional image of the Sun’s corona as the solar wind is forming.

Three of the satellites are equipped with Wide Field Imagers (WFI) to observe the solar wind. The fourth carries a Narrow Field Imager (NFI) coronagraph that will focus on the Sun’s outer atmosphere constantly.

“By combining the NFI instrument and the WFI instruments, all four of the spacecraft together piece out this enormous three-dimensional, 360-degree view of the solar system,” Viall said. “And so, in this way, PUNCH is able to take high-resolution images and combine that with a global viewpoint.”

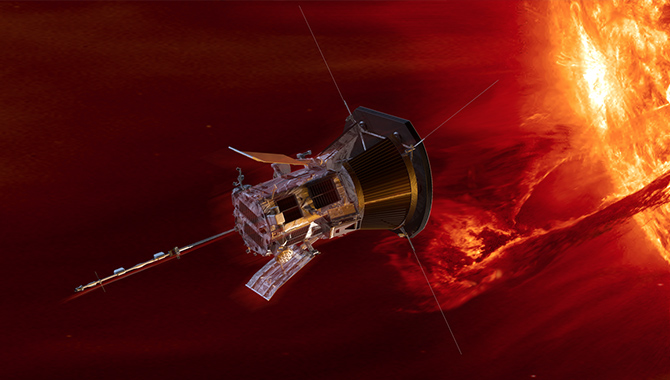

The mission will also shed new light on Coronal Mass Ejections, events that have the potential to disrupt technology and communication on Earth. The mission’s data will also provide a different context to supplement other NASA missions studying the Sun, such as the Parker Solar Probe.

“PUNCH makes artificial eclipses by blocking out the main body of the Sun, so that we can always see the corona. And it does this with an extremely wide field of view so that we see not just the corona that you get to see during a total solar eclipse, but also that corona as it expands out through the whole inner solar system and becomes the solar wind,” Viall said.

To learn more about PUNCH and follow along as the mission progresses, click here.