NASA’s Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation Deputy Manager Steve Rader discusses driving innovation through crowdsourcing and the gig economy.

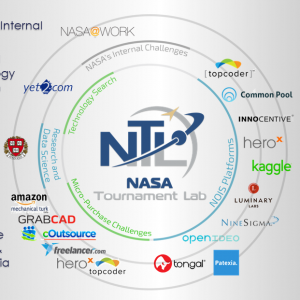

The Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation (CoECI) collaborates with innovators across NASA and other federal agencies to assist with crowdsourced challenges to generate ideas and solve tough, mission-critical problems. CoECI challenges are managed under the umbrella of the NASA Tournament Lab, which offers a variety of open innovation platforms that engage global crowdsourcing communities in challenges to create innovative, efficient and optimal solutions for real-world problems. CoECI fosters collaboration within the NASA community through NASA@ WORK, an agencywide, virtual platform that seeks to increase innovation and offers challenges for NASA employees to contribute to interactive discussions and submit solutions.

In this episode of Small Steps, Giant Leaps, you’ll learn about:

- What makes crowdsourcing a significant catalyst for innovation

- Why solutions often come from someone outside the principal domain

- How NASA project managers can prepare for transition to the gig economy

Related Resources

Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation

Episode 29: Centennial Challenges (Small Steps, Giant Leaps Podcast)

APPEL Courses:

Creativity and Innovation (APPEL-C&I)

Critical Thinking and Problem Solving (APPEL-CTPS)

Types of Contracts (APPEL-CONT)

Steve Rader

Credit: NASA

Steve Rader is the Deputy Manager of NASA’s Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation (CoECI), which is working to infuse challenge and crowdsourcing innovation approaches at NASA and across the federal government. Rader started his career as an environmental control and life support systems flight controller for Space Station Operations and has worked at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston for over 25 years. He moved into flight software engineering and developed delay-tolerant communications software for the space shuttle and International Space Station. Rader led the development of the Constellation Program’s Interoperable Command, Control, Communications and Information architecture and later supported the Mars design reference mission definition and a number of analog missions studying space mission operations and design. He has a bachelor’s in mechanical engineering from Rice University.

Transcript

Steve Rader: If you really want to work this way with the latest and greatest, you have to find new ways to do that. And it turns out crowdsourcing has the magic necessary to do that like nothing else we’ve been able to find.

We really have this amazing workforce that is at its heart innovative. When you combine that and these external challenges, we get this kind of superpower for finding innovative solutions.

The gig economy and freelance economy and crowdsourcing challenges all kind of merge into one area that’s starting to define the future of work.

Deana Nunley (Host): Welcome back to Small Steps, Giant Leaps, a NASA APPEL Knowledge Services podcast that taps into project experiences to share best practices, lessons learned and novel ideas.

I’m Deana Nunley.

Today on the podcast we’re talking about crowdsourcing and the gig economy, and their influence on NASA mission success now and in the future. We’ve got a lot of ground to cover, so let’s jump right into our conversation with Steve Rader, the Deputy Manager of NASA’s Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation.

Steve, thanks for joining us on the podcast.

Rader: Well, thanks for having me.

Host: Could you give us an overview of NASA’s Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation?

Rader: Sure. So we are a small group that works across the entire agency and, in fact, across all federal agencies to help promote what we call open innovation so these are crowdsourced challenges that we do using what we call curated crowds, which are companies that are out in the world that have put together really large communities around various topical areas, problem solving, software, algorithms, data science, film. And those communities are used to solve hard problems and to get some really high-quality products that we at NASA really can use to make progress on our goals and challenges.

Host: You’re reaching out to these other companies, other individuals. What is it that makes crowdsourcing such a significant catalyst for innovation?

Rader: Oh, that’s a great question. So innovation is one of these kind of interesting areas, right? In fact, we get a lot of eye rolls when we talk about it because a lot of people like to talk about innovation but it’s one of these kind of elusive things on how do you get it. But what we do know from a lot of the research and literature out there is that one of the things that’s important for finding those really useful, novel technologies and solutions is diversity and really getting outside of the normal study and the normal groups that do that because a lot of times those technical groups have really plowed the ground well, right, around a given topic here. So, they all kind of have the same experience in trying to solve a problem in a given domain.

And what we find is that the most novel and most useful solutions often lie kind of outside of that domain and in either another area or in just the diverse thought that’s out there and so crowdsourcing is a really great way to find those people that have the experience maybe even in another domain or they can just see the problem differently and they can connect the dots. One of the things I talk about a lot when I talk to folks is that we live in a really different world than we did just 10 or 15 years ago. 90 percent of all scientists that have ever lived in the history of the world are alive today. If you look at the curves for how many patents there are, there used to be just a few hundred thousand a year. Now there’s over three-and-a-half million a year. If you look at PhDs, the same thing.

We’re undergoing this real big technology explosion that I think everyone’s aware of. We just might not appreciate the scope. But a lot of what’s happening is there’s a lot of these building block technologies like machine learning and 3-D printing and drones and cheap sensors and people are out there really tinkering with these things in different ways and doing research in different domains where the combination of those to try to solve other problems is just creating lots and lots of solutions that are out there that we can actually use. But if we were to see those solutions, say there’s a farming technology which is combined drones and machine learning and maybe some other technologies, we might see a presentation about that and think, “Well, that’s great for them, that’s not helping us.” But someone who understands kind of the lingo and what’s going on in that domain and understands our domain can often connect the dots and say, “Oh no, with just a few tweaks, we can take this amazing technology they’ve come up with and apply it to something at NASA.”

And, suddenly, we get this 5X, 10X improvement in our performance that we’re needing in order to solve the problem. And that kind of diversity is proving itself out over and over. We see lots of challenges where most of the time is being solved by somebody that’s not in the same domain as the challenge and a lot of times they’re bringing solutions that exist already. And what that provides for us is a much better starting point to then take that technology, that idea and build on it to go do some just really amazing stuff.

Host: Steve, let’s dig a little deeper into that. Why is it that solutions often come from someone outside the principal domain?

Rader: A lot of times the teams that are already attacking these problems, they are really using all the same assumptions. They’re using tried and true methods. And it’s hard for them to see what’s out there. It’s hard for them to connect the dots to other domains. And that’s where the crowd really is good at that. And on a crowdsourced challenge, which is kind of what we use to access this power of the crowd, we’ll put a prize or incentive out there. And the people that come in to work on these, they often have a passion about NASA or a passion about the domain that we’re working in and they’ll put in time coming up with a solution and proving it out and showing you what they’ve come up with in doing research, even doing some prototyping.

And what we find is — one of the things about innovation is that you’ve got to have lots of failure, right? You’ve heard that, fail early, fail often. When we do that internally, that’s an expensive proposition, it takes a lot of time. When we do a crowdsourced challenge, what we show over and over is that we actually get lots and lots of failure, right? Because you’re only going to actually select the ideas and designs that are going to be value add. What’s easy to miss is the often thousands of people that have actually tried to do something to solve your problem but have failed. And oftentimes it’s that failure that’s necessary to actually kind of weed out and find the things that will work. We just see that that kind of churn is as the necessary steps in order to find innovation. But for us it comes almost free, right? Because we’re putting a prize out there. We’re only paying for the good stuff.

Host: Let’s talk more about how you maximize these opportunities to engage crowdsourced communities. What do you do that helps to find these innovative solutions?

Rader: Gosh, there’s a couple of things. We start off, we really encourage the teams and work with the teams to really understand their problem. We find a lot of times, a big chunk that we miss in the problem solving in the innovation world is that we don’t spend enough time really understanding our problem and getting on the same page and understanding what it is we’re trying to do. And, so we have a lot of methodologies for kind of doing that. But then also we don’t just put a challenge out to the public. We use what we call curated crowds. And these are communities that have been put together around a passion, right? So, a crowd we use is Topcoder, right? And they’re 1.5 million software developers and data scientists. Well, if you think about how that community came together, Topcoder established itself, and they had to draw those folks in and the folks they draw in aren’t people that don’t know anything and have no interest.

It’s the people that actually are very passionate about software and data science, and they join and connect in these curated communities to find other people that have that passion to learn more, to engage in challenges that will kind of upskill them and get them a reputation for being a great coder. And those are really handy attributes because also those companies are exercising their capabilities within those communities by running challenges regularly. So these people know what it means to participate in a challenge. They know what their odds are, they know how to up their odds, they know how to deal with the kind of terms and conditions that are put out there in the legalese. And so that kind of ease of working in this space creates a much richer area where we can post a challenge, get a lot more participation from people who will actually make a difference.

And these companies are really good at kind of posing the problem correctly, right? There’s a great example I use over and over where a company was brought a commercial challenge to remove grease from potato chips, right. The way they did that commercially was they would vibrate the chips on a tray as they came out of the oil and that would break a lot of the chips, but it would shake off the grease at the same time, but they had a yield problem, right? And I also often point out that’s mechanical engineers that do that kind of food production work, food production line. And for mechanical engineers, vibration is a key expertise that they bring, right? And so that was their solution to vibrate the tray. They put this out on one of these platforms. And the first thing the company did is they changed the problem statement from “How do you get grease off of potato chips?” to “How do you remove a viscous fluid from a delicate wafer?”

And by just making that subtle change, right, which actually makes it sound even nerdier, right? How do you remove a viscous fluid from a delicate wafer? That’s like, well, why are you obscuring it? Well, by saying it that way, what you’re doing is instead of just appealing to food scientists and food production engineers, you’re opening up to everyone who knows about physics. And, so you’re appealing to people working with silicon wafers and biology and all these different folks. So you’re now reaching out far beyond and we don’t realize it, but when you pose a question, the words you use are going to determine who’s going to look at that. And so they did this, and sure enough they got an answer and a solution that worked that was to vibrate acoustically the air around the chips at a frequency that would kind of create this harmonic in the oil that would cause the oil to fly off the chip.

What I like to point out to people is that’s also a vibration solution that those mechanical engineers never saw, right? So, I talk about they’re blind to that kind of thing because they’ve always been working in physical vibration, right? And so even though it’s their expertise, they missed it. The person that didn’t miss it and that actually submitted that was a violinist who I like to think of as also an expert in vibration, but from a very different way. And she’d seen the rosin fly off her bow at various frequencies and so she submitted the idea.

So then this whole idea of innovation coming from different places is often that, and what these communities have done is they’ve kind of maximized that equation, right? So they know how to pose the problem. They know how to bring in diverse crowds. You look at crowds like InnoCentive and NineSigma and HeroX, the membership of those communities, they’re not like Topcoder where it’s all people interested in one thing.

They’re actually all interested in problem solving, but they’re from very different backgrounds. So, you get engineers, you get scientists, you get artists and musicians and they’re all in this one community and they all kind of bring that kind of problem-solving mentality to it. It’s those people that you know, right, that remember all of the math and science from high school and college or they’re the ones that are actively involved in playing in bands and being over here in other activities. And it’s the makers of the world and they’re just really good at solving other people’s problems.

Host: Steve, you’re talking about this potato chip example, which is so fascinating and how communities come together, different people, different walks of life, and this all comes together. How is NASA using the power of crowds to drive innovation and transformation?

Rader: It’s a great question. We actually had a similar incident to the potato chip, right? So, we had a group of scientists, heliophysicists, trying to get a better prediction time on solar flares, right? We have astronauts that go outside the space station. A solar flare can be very devastating. And while they can kind of have some safe zones within the space station where they can get more protection, if you’re out on an EVA, it can take hours to get all the way off the end of the truss and out of your spacesuit and back into that safe zone. And we had about a two-hour prediction capability, which was not a lot of margin, right?

So those scientists posed that question out on a challenge and we got lots of great responses to that. But one thing we got was a prediction algorithm from a retired cell phone engineer who happened to have a undergrad degree in heliophysics that he never used, right? So, he was one of these people that could actually put together the dots. And what he figured out was that the math required to kind of extract signal from noise that they use in the communications world could be applied to the heliophysics problem to actually create a better and different approach for predicting solar flares. And in fact, his prediction algorithm showed something like an eight-hour prediction capability — so a 4X improvement. Now, there are things that still have to be worked out and they’re still working with that. But that’s that kind of bringing something new to the equation that we didn’t have and using challenges to do that.

We’ve done over 400 challenges now and that includes working with I don’t know 20 or 30 other federal agencies to do work on those platforms, too. But a whole host of work has been done ranging from Robonaut machine learning algorithms to software for the head nutritionist trying to collect crew data using a software app developed by a Topcoder and the crowd members there.

We’ve done challenges– really a whole host of new challenges have come out that are really cheap that are great for public engagement around graphics. And we’ve done a whole bunch of patches and logos for projects that just wanted to have a logo representing their team. And it’s really great because we can post those out there and award a three- or four-hundred dollar prize that within just about a week or two we can get hundreds of people working to collaborate and to actually come up with logos that our teams can use. And we get emails from these people saying, “I’ve always wanted to work for NASA and do something for NASA. Thank you for letting me be part of the mission.”

And they will have come up with a logo that we use. And so I tell people, we do all this public outreach where we as NASA over the last 40 years have said, “Hey, look at this great stuff we’re doing.” And there’s kind of an implied message, “Don’t you wish you were us?” And they do. And these challenges, give them a chance to participate in what we’re doing as an agency and feel like they’re part of moving our nation and our world forward in this endeavor for human exploration and just space exploration.

Host: Inside the agency, how does your group promote innovative solutions internally from NASA employees?

Rader: Yeah, that’s actually where we started, right? The first thing we talk about is that NASA has one of the most innovative work forces in the world, and we do absolutely. And, so one of the first communities we stood up back in 2010-2011 was a community called NASA@ WORK. And it’s a platform, an ideation platform that has now grown to have a membership of about 30,000 so almost half of all NASA employees and contractors are now on this platform. And they actually help execute all sorts of challenges to find solutions, to find people that can work on different solutions, ideas. We actually just wrapped up our COVID challenge that we put out when the COVID virus started to become a really big problem. And we put the challenge out to the workforce of, “Hey, how can we use our NASA brains to come up with ways?”

And I think it was a two-week challenge, which had something like 250 ideas, but 150 of those ideas came in the first 24 hours. Our workforce just went to town on these and we ended up with over 500 comments and something like 4,500 votes. Just trying to evaluate all these. And one of the things that came out of that was the JPL ventilator that they developed and is now going forward. They did that all in 37 days total. They’re right now looking at 3-D printing protective gear, the PPE, data science around how we take our Earth science data and actually use that in ways to do mapping and other things, virus detection. I know that they’ve just really been impressed with what’s come out of that. It was a whole bunch of really great ideas about donating PPE and using NASA facilities and astronauts being used for public service announcements for social isolation, volunteering services, all of that kind of stuff came in, just some really wonderful engagement.

But we’ve been using that crowd for years now and I will tell you what it is really, really good at is breaking down the silos that we have. All large organizations have silos. And it’s really a feature, right? Because we have really hardworking people that go heads-down on their projects and they work really hard to deliver Orion or get the next supersonic aircraft technology proven out or to get Mars exploration going even more than it’s already been done.

And it’s fascinating because that hard work means that they’re not able to pull their head up and share that information or see what others are doing. And so what we find is these NASA work challenges are really great for what I call enterprise knowledge sharing. When you ask a question, “Hey, how do you do this?” or “We need help on finding the solution to this,” what we find is people do see the emails and if they don’t know anything about it, they delete the email. But if they do see something that says, “Oh, that’s related to something I work on,” then they open up and they share, and they tell you what they’re doing. And it turns out that just that, creates this really great rich way for us to find the solutions that are latent within our own organization.

A great example of that was early on in the program, we had a scientist in the Human Health and Performance that was looking for a better way to monitor and measure urine volume in microgravity. I actually used to work on the shuttle system that did urine monitoring back when shuttle was still flying. And it’s this huge piece of equipment that rotated a drum with urine to kind of measure that in microgravity. And it was really interesting, but it was really big. It took a lot of power. And let’s face it — when you spin urine, bad things can happen, right? It’s just not something you want to do if you can help it. So, they were looking for a better, lighter solution that would be more accurate. And, so they ran a NASA@ WORK challenge just to see, does somebody else have an idea that might be brought to bear?

And it turned out literally 300 yards away from where this guy sat over in a different directorate, different division, working on a different problem, was a solution that when they gave it to this guy, he said, “Oh gosh, this is going to save us five years, one and a half million dollars, a whole SBIR cycle, a Phase II SBIR trying it.” And it gave them this huge head start on taking that and making progress. So, we see that over and over that we get great ideas and let’s face it, we even get those novel great ideas that just come out of nowhere, right, because, we really have this amazing workforce that is at its heart innovative. When you combine that and these external challenges, we get this kind of superpower for finding innovative solutions, which is what we need because we have really, really hard problems.

Host: Beyond harnessing the power of NASA’s workforce and supporting innovation on internal platforms, how far-reaching are your group’s challenges and tools? And what level of impact are you seeing?

Rader: We currently have 18 different communities that we can use and those total about 70 million people worldwide when you add them all up. And so it is a really robust capability that we have an ability to reach out to. And we’re about to launch what we call the NASA Open Innovation Services Contract. Our second one of those, so NOIS II is what we call it. And that contract is actually going to more than double the number of vendors we have and increase the number of potential solvers, those communities to over a hundred million people, which is basically the equivalent of two thirds of the US workforce or 1% of the entire human population. That is an incredible reach. And these people can bring all sorts of amazing stuff to bear — knowledge and expertise.

One of the things that we’re fighting as an organization, like everyone, like every large organization has this problem right now, and that is how do you keep up with the rapidly increasing rate of technology change? We used to be able to bring all those experts in and hire them but things are changing so fast now. You can’t hire people fast enough, and that model doesn’t really work anymore, right, because if you have to hire more people than you only have so much budget, you either have to get rid of other people or find more budget. And that’s really hard. And so we’re finding that there’s these crowds that we can tap into that quite frankly have some of the world’s experts in these emerging fields in data science and quantum physics. And while we have really great scientists and engineers, if we can tap into these other folks to find those best starting points and to tap into that new knowledge that’s coming out every day in those new technologies so that we can apply them to our projects, that’s really going to help us stay relevant and stay up with the challenge.

And that’s what we have to encourage our folks. We say have to say, “Look, I know for years we were the experts and we were the ones that had to come up with this all, but now we live in a new world where we actually have to employ everyone’s efforts around the globe if we hope to stay competitive.” And we’ve come up with a model, we think, that’s very collaborative and starts to use the best of our workforce combined with the best of what’s out there to find these best starting points, these best ways to intersect the two and get a really bigger bang for the buck, if you will.

Host: Are there other challenges or obstacles to your work that you have to overcome?

Rader: Oh, there’s so many. This is culture change, right? Anytime you have something new it’s a problem. I don’t know if you remember when Uber first came out. But I remember everyone I knew, including myself, thought and talked about it as, “Why would anyone ever get into a stranger’s car? That’s crazy. That is a crazy risk.” But now what do we do? Everyone uses Uber. There’s a trust that has to happen. And it has to be built on what that can do and what is our role, right? When I started at NASA, we had an entire building next to the building where I worked that was full of draftsmen. And those people don’t work at NASA anymore. We have a handful of CAD engineers, a fraction of what we used to have.

The world changes and we have to adapt. And sometimes that’s scary. And one of the big barriers is our workforce, because they’re so innovative, they’re also resistant to this, right? They think they’re giving away the most fun part of their job. And I get that, right. You come to NASA to be the innovator. And what we tell them is, “Yes, we absolutely rely on you being the innovator.” But you would never start a project with a 10-year-old computer or an old piece of software, Lotus 1-2-3 when there’s new Excel out there. You always bring the latest and greatest technology to bear if you’re serious about solving a problem. And that’s all these are, these are tools. And if you want to succeed, you use the tools that can get you the best starting point. So then you can go innovate using the best tools, the best technologies, the best knowledge.

And so that’s what we’re pushing. But I will tell you when people have worked here for a long time, and I’ve worked here for 30 years, so I totally get it. When you get assigned a project to go build the next lunar lander or to work on a new technology, the first thing you do is you draw on your last experience. And the last thing you did probably was you went out and Googled, “Hey, where do I find the latest and greatest technology?” And what we have to tell people is you actually can’t find that stuff that you really need with a Google search. It doesn’t exist in that capacity. It has to be translated. Somebody has to connect the dots for you. If you really want to work this way with the latest and greatest, you have to find new ways to do that. And it turns out crowdsourcing has the magic necessary to do that like nothing else we’ve been able to find.

Host: What are some of your favorite success stories over the years?

Rader: Oh gosh. So many success stories. Some have actually been for other federal agencies. We actually have been a part of some really neat initiatives. One of my favorites was early on we helped USAID, which is the agency that works with other countries to distribute foreign aid that we give out. And they actually ran a challenge on predicting human atrocities. So taking — kind of like we take telemetry data from the space station or from a rocket– they actually have State Department data that comes in about how many uprisings and what kind of government’s going on and all of the activities in all of these countries all around the world. And they were able to take that data, and Topcoder actually developed a predictive algorithm that could, with quite a bit of accuracy predict when a country is likely to start a genocide.

And I just thought that was amazing. We worked with Homeland Security on a couple of challenges recently, one to help with the screening algorithm used at the airport, right, as people are go through those scanners and the millimeter wave scanning technology, they’re improving, but the algorithm’s been pretty bad, right? Every fifth person gets patted down. And we ran an algorithm there that actually turned out to be a 98 percent accurate algorithm. And they found that that was the best two-and-a-half million dollars that they had spent in a very long time. We’ve done several follow-ons with them, including this last year we did an opioid detection challenge to try to find opioids that are being sent through the mail. And they actually found some really nice results out of that are in the middle of implementing the results from that challenge.

At NASA, gosh, we’ve done little things like working with the folks, working the inflatable habitats to find them a better way to measure strain. And in Kevlar and Vectran, they were really going quickly and needed to find a solution. We were able to find something for them very quickly that they said, “We got this so fast and so inexpensively. And when we got it, we asked ourselves, ‘How did we not know about this? How did we not think of this ourselves?’” We’ve done numbers of algorithms for say the REALM project, their RFID project, we were able to model the space station’s solar rays to maximize the output and prevent shadowing. And to do that in ways that were really innovative and cost saving. What, gosh, I can literally go on and on, on the different challenges that we’ve done. When you have over 400 to choose from, it starts to be this thing where you start to just drone on and people at parties start walking away from you when you talk.

Host: So many interesting stories to share, and this isn’t the only program within NASA that does challenges. We did a podcast episode a few months ago that featured Centennial Challenges and had a fascinating interview with Monsi Roman talking about a lot of the challenges they do. What’s different about the challenges managed by Centennial Challenges and the ones the Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation does?

Rader: Yeah, well we’re actually all part of the whole Prizes and Challenges Program at NASA. So they’re a sister organization to us. They’re really terrific. They do some amazing challenges. They’re really closer to what you think of for say an X-Prize or the DARPA self-driving car challenge where there’s similar to those where they put really large sums of money out with the intent of universities and startups and industry coming together to form teams to work on really complex problems to sort of system problems.

We actually differentiate ourselves because we provide really smaller problem solving. We do have vendors that can do the larger stuff and we’re looking at how do we make that spectrum as full and kind of continuous so that no matter what your problem, there’s a place to plug in and get a solution. But our curated crowds are different. They are really good at different areas. Like Kaggle and Topcoder are really great at algorithms and software while an InnoCentive or Luminary Labs is good at these bigger problems. We also do technology searches and we do smaller challenges around video or graphics and animation or ideation. I would say we actually have an entire suite, right? So, Centennials is kind of at that high end. We’re kind of at the next step with our challenges, which we actually cover with the brand name NASA Tournament Lab, and that’s our public-facing name. And we do all of those kinds of challenges that go from say millions of dollars all the way down to we can do a 50 to $100 challenge on some of our freelance platforms.

And then there’s things like The International Space Apps Hackathon, which is the world’s largest hackathon. It’s done once a year. It falls under that umbrella as well. It is, like I say, the world’s largest hackathon with I think over 225 events, something like 30,000 participants last year. In fact, they’re doing a special COVID hackathon using that platform in that group at the end of May, on May 30th and 31st. They’re going to do a COVID virtual hackathon that day. And so that’s one platform. We have our NASA work platform as well. There are the education challenges like Big Idea and others that use challenges to engage students. And then we have a really rich citizen science program under that umbrella as well where we will post a project – we, being the larger team — where projects can post their data on platforms like Zooniverse and have citizen scientists working on that data to actually do real discovery. They have great stories where there was a recent citizen science team that actually made a discovery about a new kind of Aurora Borealis. It’s kind of funny; they actually named it Steve, which I find really great.

And so there is just all sorts of fantastic work going on in the crowdsourcing world and in Prizes and Challenges and we’re just glad to be a part of it But yeah, we work very closely with those folks because when we work with projects across the agency, oftentimes one of our big jobs is to figure out, well, what’s the best way to solve your problem? And we have lots of different options there. Ranging from free with the hackathons, in-space apps or with NASA@ WORK. Those are all free to NASA projects. Citizen science has a way where the public works for free and so there’s not a prize involved in that. People work on those platforms because they’re passionate about the science. And then we have this kind of a range in both prizes to do that, cost for us to do that as well as the prizes that are offered.

Host: How do you see crowdsourcing shaping or redefining the future?

Rader: Oh my gosh. This is an area that I work on quite a bit, which is we’ve noticed when we were working with all these curated crowds that they started to overlap with freelance crowds. And when we looked closer at that, we found that these communities of passion are coming together, really in ways that are designed to accidentally almost to keep up with this rapid change. So, the gig economy and freelance economy and crowdsourcing challenges all kind of merge into one area that’s starting to define the future of work. And there’s a big trend going on right now that’s really — nobody individually is promoting it — but workers are moving out of full-time employment with companies and into the freelance workforce at a rate that if it keeps up, and in fact this COVID timeframe that we live in seems to be accelerating this trend, then in just a few years, there will be more people working full-time freelance than there are working for companies directly.

And that has huge implications for us, right? And we think it’s driven a lot by this need to have different talent, but not full-time, right? So, you need a data scientist team to help you with the emerging data sciences coming around, but you can’t afford to bring on a huge team. And so you might just need somebody for a little bit. And that goes on for all these new technologies and even bringing on someone for a little bit starts to infuse some of those new technologies and new ideas into your teams. So it’s an actual way to start infusing new technologies into your teams within organizations. And so we’re doing a lot of that kind of work. I’ve actually started talking a lot more with Human Capital folks on how this starts to affect our ways of staffing the agency.

And it could be that in the future we’re going to talk about the contributors that are in the public in similar ways that we talk about our employees and contractors today, so that instead of just the 60,000 of civil servants and contractors that we talk about being the power behind NASA, that we could have a million people working in various capacities that are the contributors to NASA and NASA’s mission, right? It’s not that they replace those contractors or those civil servants, they just start to augment them in new and flexible ways and new employment models that start to leverage people on different fractional levels at some level. And we’re trying to figure out how that works. But again, it’s something that we’re not promoting. We just see the tidal wave coming and we’re trying to figure out how do we as an agency need to tap into that so that we’re ready for it and that we can utilize it to the maximum benefit for the agency and for our mission.

Host: What can NASA program and project managers do to prepare for this?

Rader: I think part of it is we’re starting to offer more and more services that start to look like that. So, our new contract has the ability to reach out and pull in experts that are freelancers and to start exercising some of those new methodologies. We have the open innovation, which I think starts people down that path to start budgeting for different types of outreach. So right now we budget for civil servants, we budget for our contractor, we budget for materials. I think we have to start looking at changing our contracting model so that we can start to actually use more of these tools. So that means we’ve got to start carving out more budgets and trading some of that so that we’re using those budgets to run challenges, to reach out to freelance experts when we need them and to start experimenting with what does that start to look like? How do we do that in a way that’s complementary, that it protects all of the things that we have to keep private? What are the new features for security that are related to that with the products?

And all of that’s being worked because the industry’s moving that way, right? So, all of the same kind of caveats and hesitations people have are being actively worked, but the adoption side I think is the hardest part. And that’s where we have to have those managers start to reach out and to be willing to look forward and work with us and we have several ways we can help them with that.

We call ourselves the Sherpas, right? So, our team, we recognize the big barriers to getting all this work and how it’s changing, so we call ourselves Sherpas because we’re here to help you. We have the contracts in place already, so you don’t have to do that. We have processes, so you don’t have to come up on that on your own. We basically walk with folks through this to help them with that transition, to help them learn, and to make that as easy as possible and as inexpensive as possible.

Host: Steve, this has been great fun getting to have you on the podcast. We really do appreciate you joining us today.

Rader: Oh, thanks Deana. This has been a blast. I love talking about this stuff and I really look forward to what the agency’s going to do with all of this because it’s an exciting time.

Host: Do you have any closing thoughts?

Rader: Oh gosh. I’m so excited about the future. I think there are so many great things that the agency’s trying to do. Our agency is really leading the way in the federal government in this whole area. And I think our workforce is poised to kind of show as an example what can be done in this emerging use of crowds in this next generation.

Host: You’ll find links to topics discussed on the show and related APPEL courses along with Steve’s bio and a transcript of today’s episode on our website at APPEL.NASA.gov/podcast.

If you have suggestions for interview topics, please let us know on Twitter at NASA APPEL – that’s A-P-P-E-L – and use the hashtag SmallStepsGiantLeaps.

As always, thanks for listening.