NASA’s Terry Hill and Jessica Knizhnik discuss the agency’s transition to model-based systems engineering.

Model-based systems engineering (MBSE) formalizes the practice of systems development through the use of models, resulting in quality and/or productivity improvements and lower risk. In its full implementation, MBSE moves the record of authority from documents to digital models.

In this episode of Small Steps, Giant Leaps, you’ll learn about:

- The impact of the NASA MBSE Infusion and Modernization Initiative (MIAMI)

- The current state of MBSE at NASA

- NASA MBSE success stories

Related Resources

Systems Engineering and Model-Based Systems Engineering Stakeholder State of the Discipline

Webinar: Systems Engineering and Model Based Systems Engineering Stakeholder State of the Discipline

Model Based Systems Engineering

NASA Model-Based Systems Engineering Community of Practice (NASA Only)

GSFC MBE Workshop: Moving Toward Model Based Systems Engineering

APPEL Courses (New courses coming in late 2021):

Foundations of MBSE (APPEL-vMBSE1)

Model Based Systems Engineering Design and Analysis (APPEL-vMBSE3)

Terry Hill

Credit: NASA

Terry R. Hill serves as the Lead of the NASA Model-Based Systems Engineering Leadership Team, which is responsible for providing recommendations for an executable strategic and implementation approach for delivering MBSE methodology and interoperable tool chain to usher the agency into the modern world of data-centric design and systems engineering. Hill also works at the agency level as the systems engineering subject matter expert as part of the agencywide tool assessment and consolidation effort. He is the Chief of Johnson Space Center’s Engineering Directorate Processes and Methods Branch, which is responsible for managing project management and systems engineering best practices, policies, and tool infrastructure as well as configuration and document management. Hill previously held positions as the next-gen Constellation Space Suit Engineering Project Manager; International Space Station Extravehicular Mobility Unit Deputy Subsystem Manager; and Deputy Program Manager of the Crew Health and Safety Program. He has a bachelor’s in aerospace engineering and a master’s in guidance, navigation and control theory from the University of Texas at Austin.

Jessica Knizhnik

Credit: NASA

Jessica Knizhnik is a Systems Engineer for the Joint Polar Satellite System, a series of weather satellites built by NASA for NOAA. She is a former Co-lead for NASA’s Model-Based Systems Engineering (MBSE) Infusion and Modernization Initiative (MIAMI) to implement MBSE at NASA by utilizing test cases and engineering expertise from across NASA field centers, industry and academia. Prior to her work on MIAMI, Knizhnik served as a Product Assurance Engineer on NASA science missions, including the James Webb Space Telescope. She completed a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering and a master’s degree in systems engineering at the University of Maryland, where she was first introduced to MBSE.

Transcript

Terry Hill: Model-based system engineering is a capability that is identified as important to NASA’s future.

Jessica Knizhnik: We were able to save like 80 percent time just in the testing and verification phase, which was pretty exciting for us. It was a great early win that we had, and it proved to us that modeling could be useful.

Hill: It’s not something completely new. So, if system engineering would work on a project in the past, 99.99 percent chance MBSE will work for you in the future, or today.

Deana Nunley (Host): Welcome back to Small Steps, Giant Leaps, a NASA APPEL Knowledge Services podcast where we tap into project experiences to share best practices, lessons learned and novel ideas.

I’m Deana Nunley.

‘Making systems engineering easier for the workforce’ is the tagline adopted by the NASA Model-based Systems Engineering Infusion and Modernization Initiative – or MIAMI – for short. We’re exploring model-based systems engineering during a couple of interviews on the podcast today. NASA Johnson Space Center’s Terry Hill, who leads the agency’s Model-Based Systems Engineering Leadership Team, will join us shortly to discuss the current state of MBSE at NASA. We’ll begin the show with a conversation with NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Systems Engineer Jessica Knizhnik, who co-led the MIAMI effort.

Jessica, thank you for being our guest.

Knizhnik: Yep, no problem. Thank you for having me.

Host: Could you give us a concise description of model-based systems engineering?

Knizhnik: Sure. So INCOSE, which is the International Council of Systems Engineers, their definition essentially says that model-based systems engineering is the formalized application of modeling to systems engineering, right? So that’s a bunch of big terms. I like using that definition because it’s one that is kind of standard that everyone across the industry might use. But ultimately what it basically boils down to is that we can use models to capture information in one place and use the models for the form of communication rather than documents. Otherwise, the systems engineering itself should stay the same.

Host: What’s the key difference between model-based systems engineering and traditional engineering?

Knizhnik: Traditional engineering and model-based systems engineering should be very similar in that you’re still doing systems engineering either way. Your systems engineering processes should all be the same. You still need to go through and define your requirements, your concept of operations, and your architecture, flow those requirements down to your development level, develop your system, verify your system after building it and testing it, and then go ahead and fly it, right? The difference, though, is that instead of spending a lot of your time recording and capturing your technical information, a lot of engineers will spend time just doing data input. That’s something that model-based systems engineering should help with. So instead of recording the data it should already be there since someone only captured it once. And if there’s a problem for instance, like say you have a mishap, now, rather than going to try to figure out what the requirement was or where it was and who wrote it down, it’s a lot easier to go and look it up within your model rather than having to call like 10 people just to track something down.

Host: The MBSE Pathfinder and MIAMI studies that you co-led helped set the stage for NASA’s transition to model-based systems engineering. Could you give us a quick explainer of Pathfinder and MIAMI?

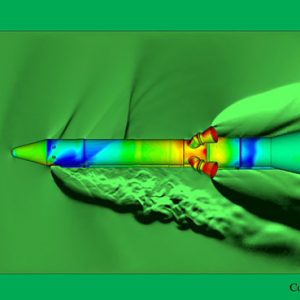

Knizhnik: Sure. So, the MBSE Pathfinder is a part of MIAMI, but it actually preceded MIAMI. So, we started in I think 2016 and we essentially got a group of engineers from across NASA centers. Over the course of the five years that we ran MIAMI we touched every single one of the NASA centers. But the first year we ran Pathfinder we basically just wanted to know if MBSE was even doable. Can we use the tools that are currently available to model the systems we had? We had, I think, five case studies, five use cases representing different projects from across NASA. We had in situ resource utilization. We had a sounding rocket project. We had an engine project. And we just got our teams together, there were about five people each and said, ‘Let’s break it, let’s see what we can model and let’s see where the limits are of what we can’t.’ And after that first year we found that, yeah, actually we could model the systems that we have now.

So, then the second year came around, and we decided to run Pathfinder again. And the next question we had is, ‘All right, just because we can do modeling, just because we can use model-based systems engineering, should we? Can we answer any engineering questions with models that we create? Is there anything that’s valuable?’ And so we did. We ran the same thing again. We expanded a little bit more. We had an additional team. We also brought in an advisory board of respected engineers from across NASA centers to make sure that we stayed on track and were actually answering engineering questions.

And we found, again, we were surprised we found that, yes, we can answer engineering questions. We learned that model-based systems engineering will not answer every question all of the time, but there are definitely situations in which we can answer questions and which we can derive value. So, for instance, one of the big wins that we had that second year of the MBSE Pathfinder is that we modeled a rocket engine, a similar rocket engine to one that we had built in the past, and we found that by using a model during the testing phase, instead of spending the time to manually check the test data that we had and make sure that it matched our requirements and met our requirements, we could use a model to automate that comparison. And when we did that, we found that in that particular instance we were able to save like 80 percent time just in the testing and verification phase, which was pretty exciting for us. It was a great early win that we had, and it proved to us that modeling could be useful.

So then from there, after the second year of Pathfinder, we sat down and that’s when we officially developed the MIAMI Initiative. And so, we said MBSE Pathfinder from 2016 and 2017 were included. And then in 2018 and 2019 we ran the Pathfinder one more time with a smaller team, looking at a sounding rocket to understand if and how we could use MBSE across the life cycle. We also added a community of practice so that other engineers and users and people interested in utilizing MBSE could get together across the agency and share what they learned, what they liked, what works, what doesn’t work, and what’s needed. And at that time, along with the advisory board that I mentioned that we had in 2017, we also added a strategy group to help us look a little further into the future. So that ran in 2018 and 2019.

And then in 2020, we used that year as a wrap-up year. We took all of the things that we learned. We developed a capability, so we had our community of practice, we had an expert advisor that we found was helpful in getting projects started with MBSE, and we had some infrastructure available to us as far as tools and cloud space go. And we did what we call the targeted deployment. And so, we picked one project that we thought would be a good testing ground for our capability and we worked with them and deployed our expert advisor tools and infrastructure and the community of practice to them and then received feedback. We got a lot of really great feedback. And so, after MIAMI ended, we used all of that feedback to make recommendations both to the agency as they developed their MBSE policy, as well as to MBSE users about what’s the best way to implement MBSE in a value-added way.

Host: What are some of the key takeaways from MIAMI in terms of the benefits and challenges of MBSE?

Knizhnik: So, we found that there are three major benefits. They are first, you can have improved communications. So that’s as easy as I think an example I mentioned before, rather than searching for documentation of which document is the right document, which document has the right answer, where do I even go, it’s easy to go to one spot and look in that one spot for the information that you want. So that’s improved communication. Everybody is on the same page.

There’s also enhanced knowledge transfer, which is a little bit different than improved communication. So improved communication is between different groups working on the same project. So, say we had a group from NASA and a group from JAXA working together. They could use a model to communicate the same information to each other, whereas enhanced knowledge transfer is more of like if you’re going to communicate across projects that are similar, but not the same. So, for instance, at Goddard we have a lot of weather satellites. Those weather satellites have a lot in common so being able to reuse information from one model to the next would be incredibly helpful between those different projects, so you didn’t have to start with a blank piece of paper essentially every time.

And then the last thing is managing a complex system. We found that MBSE, one of the major benefits is giving your engineers an opportunity to be able to look at their system as a whole rather than different piece parts. You can look at it all together and because our systems are getting more and more complex, having it in one spot and one spot that’s not always in the written word. So, model-based systems engineering allows you to look at your system in a more visual kind of way. There’s a lot of graphical notation that goes with it. That can really help an engineer understand what they’re looking at.

So those were the three major benefits, and we found overall, obviously, if you can find value in it in another way, we certainly encourage that. But we found overall that if you start by looking at one of those three major areas and trying to build your MBSE implementation off of a small portion of that, you’re most likely to get some benefit out of it.

And then I think you also asked about challenges. There are a few challenges. The two major ones are that first, there is a learning curve with it and some startup costs. So MBSE does take more effort upfront. So, putting in all of your common information, so there are libraries of information that you may need from other projects, inputting a structure into your model that everyone follows together, as well as just learning the tools. Yeah, that does take some time and investment up front. And that’s one of the reasons that we implemented the concept of an MBSE expert advisor. We really found that that helped our Pathfinder projects get over some of those initial learning curves and speed bumps, was to have someone who could walk them through some of the difficult parts in the beginning.

And then the second area that’s still a bit challenging is the technology and the tools. There are certainly a lot of great tools out there, but they still need to evolve, and we still need to really understand how to use them specifically within the NASA environment. So, for instance, configuration management. That’s not something that most of the tools that we’ve seen so far naturally do well. So instead, what we’ve had to do internally to NASA is come up with a model management plan, essentially a configuration management plan, for our models.

So over time we are hopeful that by working with the tool vendors and understanding what’s really involved in our collaborative environments, we’re hopeful that the tools will evolve as well and that they’ll also be more open to enabling us to share information with others outside of NASA. The tools can do that right now, but because we are the government, of course we have a lot of security restrictions, so making sure that the tools can work with our restrictions and make sure that the restrictions are the correct restrictions. And so that’s a conversation that needs to be had at a more agency level. What are the correct restrictions that we need to have that our tools need to meet? Those sorts of things are still evolving.

Host: What are the next steps in NASA’s implementation and application of MBSE?

Knizhnik: From a tactical level we want to make sure, as I mentioned just now, that the technology and the tools continue to get updated, that we work with our tool vendors and work internally to understand what we need. We need to keep up with that, make sure that the tools we have now are not the final be all, end all of tools. We need to also grow the knowledge base that we have. On MIAMI we did a lot of great work, I think, developing the capability, understanding where MBSE is and is not useful. We developed a preliminary community of practice and developed this concept of advisors, but that really needs to be expanded. There’s a lot more that MBSE could do that we just haven’t been able to do yet. We really recommend that the COP and an increased presence of advisors across the agency is available for people because, ultimately, on MIAMI we believe that with the support of the agency level management it’s really the engineers on the engineering level and word of mouth between them of what’s valuable and what’s not that’s really going to spread MBSE.

So, all of these other things that I mentioned like an increased presence of advisors for programs and projects and users to pull on and updated tooling and technology, that’s really so that our engineers have some place to go to and can feel confident that they can gain the benefits of MBSE. And that’s really the next step, is making sure that our engineers can do that, that they actually find value with it. We’ve proven that there can be value, but now we just need to work at expanding it. And so that’s all on the tactical side.

As far as strategy goes, we did spend some time on MIAMI with our strategy group thinking about all right, well, so we’ve got MBSE, the concept that you can use system models to communicate your systems engineering. Where do we go from here? What are our next steps in like five years, but also what are our next steps in 20 years? And on MIAMI our strategy group did put out a NASA technical memo on what that might look like, but that’s just the beginning. We think that the agency needs to spend some time planning now for what the future will be. What does the technology look like long-term? Do we just have separate tools for each of the disciplines or is there one tool that’s really useful for everybody? Or is there some sort of middle ground? Who owns all of this data? Where does it all go? What would a realistic, but more advanced modeling world look like for NASA? And then, importantly, what do we need to do and where do we need to invest now in order to get there? Those are some of the questions that are still open for us that we suggest that people look at into the future.

Host: So, Jessica, are there MBSE success stories at NASA in addition to what you already spoke with us about?

Knizhnik: Yeah. So, I mentioned before the 80 percent time savings on a rocket engine that we found, but we’ve actually found a number of successes and success stories through the MBSE Pathfinder. Another one that I think is really cool is the XRISM Project. They’re working on the Resolve instrument as a collaboration between JAXA and NASA and what they found was that MBSE helped them to overcome their language barrier, right? I mean most of the team on the NASA side doesn’t speak Japanese. The Japanese collaborators, thankfully, they spoke a lot more English. But there are some language differences. But when they were able to standardize and use the same model to communicate back and forth with standard language definition between the two of them, they were actually able to iterate on their requirements faster and better understand and be on the same page with what their requirements were and what would and would not happen. And actually, I had an opportunity to look at one of the Japanese models that the JAXA team created on their side, and even though it was all in Japanese I could look at their model and get a basic understanding for what was included and what was not included in their system. And I think that that was a really powerful success story.

Another one on the human side is within the Human Research Program, the exploration medical capability. They use models to communicate with their clinicians, so like their doctors and nurses and other medical professionals that they work with. And they were able to use modeling to make their systems and their solutions easily understandable between engineers and their clinicians which again, I thought was a great success and something pretty simple that most people starting out can do.

Host: Well Jessica, thank you so much for taking time to join us today. This has been really interesting.

Knizhnik: Sure. No problem. I’m really glad to be here and spread the word and knowledge about what we’ve been up to.

Host: And now we bring in Terry Hill, who leads NASA’s Model-Based Systems Engineering Leadership Team. Terry, thank you for joining us on the podcast.

Hill: My pleasure.

Host: What are some common misconceptions about MBSE?

Hill: Well, I think a lot of that misconception that we have right now is that it’s a bridge too far. It’s a technology that’s just too far beyond or methodology beyond what we do today, or it’s too different than what we need to do today. Or there’s a fear of the amount of investment that it’s going to take to do it. And a lot of that has to do with just being able to communicate what you do in terms of getting a return on investment and what it would take to get us to that position, or just to relay fears that it’s not a radical departure in the way we do business. It’s an augmentation. It’s just like moving from accounting ledger books to a spreadsheet, right? The basic principles of accounting don’t change, it’s how you manage the information, and sometimes the tools that you use to do that with.

Host: How would you characterize the value or the ROI of model-based systems engineering?

Hill: Well, that’s a good question. And some would argue that’s a $60 million question. It’s hard to answer, but it’s an answer everybody wants to know, right? As it is with incorporating best practices in business or in any facet of business, it’s just like using the methodology of system engineering or project management or configuration management or what have you. It’s not so much being able to quantify in very definable nuggets of what your ROI is going to be on a project that you haven’t started, right? That’s hard. That’s like saying, if you use project management on this new project, then you’re going to save 15 percent. I can’t tell you that, right? But history has shown that if you don’t have consistent practices in some of these disciplines, you will run into problems, right? These best practices or these methodologies or these processes, they’re all put in place to ensure predictable outcomes and minimize variance and risk and what have you.

Sometimes you can see the benefits if you start incorporating some of these practices in the middle of projects, but most of the time people or companies, they don’t want to switch boats in the middle of the river, in the middle of the project, right? They don’t want to do anything different unless there’s something very painfully driving them in that direction, so that’s really kind of the problem that you have when you start talking about bringing in new discipline practices or different methodologies, same thing as MBSE. What we have seen is that with studies and interviews with organizations inside and outside of the government, they’re saying that it does dramatically cut down on the data latency between the disciplines and responsible organizations.

It seems to cut down on design errors and assumptions because of how you organize and share the information. It tends to shorten the time required to prepare for major milestone reviews, because the data is all there. You don’t have to stand down your entire project to make PowerPoint charts six weeks before the review, right? Because the data is there, you don’t have to copy and paste, and what have you. And even the reviews themselves they can be faster because you’re not having to prepare all this information and material just for that review. And these are just in early phase of the projects. And what we’re seeing later on that in the later phases of projects or programs when they start going into the operational phase of their life cycle, it tends to cut down the required designed from design to manufacturing iteration in the operation phase, and also lays a strong foundation to a new technology, a digital twin. That’s another heavily loaded term that means a million things to a million people.

But it does lay the capability to evolve into a digital twin type of capacity and in a world where we’re finding that having a digital twin instead of a physical prototype replica or physical replica is tremendously cheaper. We’ve had discussions with GM and a few of the other auto manufacturing companies, and they’re wanting to move to a digital twin environment when at all possible, so we see this going on in industry. And so, it’s only safe to assume that we will move in that direction in some capacity as well. With having said all that, in business whenever you can shorten schedule, which is what we just talked about, shortening schedules, shortening the time to get stuff done, you save money. And, of course, that’s true for NASA, but we also have the extra layer of mission success. And so, it can be a key factor between a successful mission or loss of mission, or even loss of human life.

Host: What are NASA’s plans and priorities for MBSE?

Hill: NASA, this last year has made a few steps forward in that. There’s been an agreement that MBSE, model-based system engineering, is a capability that it is identified as important to NASA’s future. And it is part of the Digital Transformation effort, which also was initiated this last year. And I think the office was stood up first part of this fiscal year 21, so we’re part of that activity. The ball is starting to roll in this direction. There are commitments being made. The MBSE portion of this stood up a team called the MBSE leadership team, or the MLT. and what we’re doing is to try and pull together a group with representatives from across the agency, from the different NASA centers that are experienced in the area of system engineering or MBSE.

We’re trying to integrate with the APPEL organization to start laying out requirements for training that needs to be provided to the workforce so that when we’re ready to go full bore on this, that the training will either be in place or have had the workforce trained as part of that. As part of this, we’re scoping out what it is that we feel will be necessary for the agency to fully embrace MBSE methodology, and also identify what structure needs to be put in place and the training like we talked about before, documentation processes, all the different aspects that are required to make a fairly substantive shift in culture and approach to workforce. And also, part of all that is making sure that your tools and your ontology is all the same, so that you don’t end up with 10 different centers doing it 10 different ways, using 10 different sets of parameters and interoperability standards.

And you know we don’t want to create the next Tower of Babel or anything like that, so we are going through this and trying to use a systematic approach to measuring our current capabilities. And we wanted to do this in a way that is based in industry, because in some regards they’re a little bit ahead of us. And so that we don’t kind of create a standard yardstick that only NASA uses. So, what we’re doing is we’re taking the model-based capability matrix, which was published in INCOSE, which is the professional organization for system engineering. And what that does is that defines, I think roughly 42 different measures, figures of merit, if you will. How you can self-assess your capabilities to what they have defined as needed areas to really define a comprehensive approach to model-based system engineering.

And along it, it has different levels of maturity, so depending upon the needs of your organization, you can kind of pick the maturity level that you feel that you need to be at, do the self assessment. And this approach also gives you a way to start developing plans to update your system and grow your capability and mature it to the levels that you want to in the different areas. Part of this is to make sure that this effort is not by itself. There are other areas of discipline that the agency is wanting to move into the model-based domain, so there’s several model-based discipline groups out there as well, like model-based project management, model-based mission assurance, model-based capital management, all that type stuff. We’re trying to integrate with those groups to make sure that we’re not silos upon ourselves, because if we’re all going into the digital domain, it means we also need to be interconnected to really fulfill the goal of what this is all about.

Host: In the first segment of today’s show we spoke with Jessica Knizhnik about MIAMI. What are your thoughts on how the MIAMI team’s effort is influencing engineering across NASA?

Hill: I think the MBSE leadership team that exists now is really standing on the shoulders of all the effort that that team went through, so in terms of the different model-based discipline projects that are part of the Digital Transformation Office because the MIAMI team went through all that effort, they effectively put us five years ahead of most of the other groups.

And that’s good because that allows those other discipline groups to look to the MBSE effort, to kind of see where the potholes may be and to really kind of leapfrog using that information. And also, there’s other groups like the ExMC project that’s led out of JSC, I believe. And it’s really, they’re looking at MBSE to manage all the intricacies of what will be needed to deploy medical capabilities for future exploration missions, so you can see we’re seeing a real gambit of different applications of MBSE methodology.

And that’s exactly what you expect, because again, it’s just the next step in the evolution in the systems engineering. It’s not something completely new. So, if system engineering would work on a project in the past, 99.99 percent chance MBSE will work for you in the future, or today.

And this really is largely a grassroots effort in terms of the MBSE domain. And this is really kind of where you want it to be when you start looking at new ways of doing business or adoption of new technology or what have you, because it almost provides a Darwinian approach to see what works and what doesn’t work for your specific org or business unit. But at some point in time along that journey, you need to have the ability to bound the box, if you will, that we all live and work in to ensure that, to use a metaphor that the entropy doesn’t reign king, right? You don’t want to make sure that you get such a biodiversity that in your tool set and your usage that you can’t communicate with each other.

And that’s not always tools, but processes and information and skills. Make sure they’re all interoperable at some desired level to make sure that it meets the needs of your organization or the enterprise. At the agency level, I think it’s safe to say that we’re in that transition phase of having tested a lot of things in the grassroots level. And now with the MBSE Leadership Team, we’re trying to understand how we can make that transition to an agency capability in a graceful and deliberate way.

Host: What’s the current state of MBSE at NASA, and could you give us your assessment of how it’s going?

Hill: Well, it is still pretty early on in that assessment phase. What we’ve seen in some of the data gathering exercises that we have done is that different centers have looked at and use MBSE in a lot of different ways and to varying levels of maturity, and to varying levels of implementation across life cycle phases. Some of the groups like Goddard who have the sounding rockets, they have a long history of working using MBSE through the entire life cycle phase of a Sounding Rocket Program. We’ve got certain groups like JPL or Johnson Space Center. A large portion of our projects are early life cycle phases, either proof of concept or what have you. And because they span these election cycles, a lot of these projects never reach to fruition, so by the nature of that business alone, a lot of the experience in MBSE and some of these centers, it’s just in the pre-phase A and phase A and those types of areas, so it really does vary quite a bit across the different NASA centers.

And it also varies because of the culture that each has and their willingness to adapt and adopt to new type of ways of doing business, and what have you. There’s a broad range of what we’ve seen in the cursory look of things as I talked about earlier, the MBSE maturation tool that we’re going to use, we are going to use that. And that’s hopefully going to give us a standardized way of measuring each of the center’s capabilities. And then we can aggregate that information and present a clear story to the agency as to where we really stand almost at a center-by-center basis, but also use that to kind of draw the minimum level capability that we want to achieve during Phase One or Phase Two or Phase Three, so the agency can figure out where they want to apply the resources or the individual centers, if it’s more appropriate for them to invest in that level of activity, so they can determine really what is necessary. That’s kind of the current state right now.

Host: I think you may have mentioned benchmarking. Is NASA involved with MBSE benchmarking activities with other federal agencies to get a sense of how the engineering shift is coming along across the federal government?

Hill: Yes, there was a study performed in 2019 by Harlan Brown & Company, and they provided to NASA as kind of an industry self-assessment or with lessons learned about system engineering and BSE. I mean that is an example of engaging in a benchmarking activity outside of the NASA walls. We also participated in some benchmarking efforts from the outside, from other government agencies coming in to engage NASA, to see kind of where we are in our efforts as part of their own benchmarking efforts. And it’s my understanding that there’s going to be some NASA-initiated benchmarking on the horizon with other government agencies as we get more and more serious about this effort. And what we’ve seen and heard so far, it looks like there’s just from a government perspective, substantial potential for lessons learned from engaging Air Force and Navy in the realm of MBSE as they have clearly invested quite a bit of resources over the last couple of years to advance that capacity within their ranks.

Host: Jessica discussed a couple of challenges that surfaced through the MIAMI work. We’d also like to hear your perspective on challenges, specifically as you promote adoption of MBSE across NASA.

Hill: What I’m going to say here won’t come as really any surprise, right? Anybody who’s ever led any form of change, a lot of this will bring up some memories. A lot of what we hear is, ‘Well, I don’t understand it, so I’m not going to adopt anything because it just infuses risk into my project, right? I know how to do my work, I’m quite successful in the way I do my work, I’m going to stick with that.’ And that’s fair, right?

Or you hear ‘I’m too busy or behind schedule,’ or ‘budget’s too tight to really spend any time to switch horses and infuse this into my current project.’ Again, spending most of my career as a project manager, I totally understand that because the last thing you want to be is in the middle of a flight project and say, ‘OK, and now for something completely different.’ That’s not what you want to do right in the middle, so I get that too. But you know, on the other end of the spectrum, we’ve got the dangerous eager beavers, right? They’re like, ‘OK, I’ll use it, but I’m going to force this tool to do things the way I’ve always done them in the past.’ And well, that’s kind of defeats the purpose as well. Because like with most of our processes that we have, the only thing we’ve done from the age of paper to the age of electrons, most of our processes today are just electronic versions of paper processes, right?

And it takes a while for people to really kind of get it. It took me a while to really let the light bulb go on. It’s that doing things data-centric is different than doing things paper-centric, because paper-centric, you’re physically bound to this three-dimensional piece of paper and the words and the information on that paper are not going to go anywhere. They are in that paper, they’re in that box or that book, that document. In the digital domain it’s in the ether, right? It’s in the cloud, it’s in databases, that data can be accessed from anywhere. Well, with that lack of boundaries, we need to rethink how we do our job and how we leverage that information when that information is readily available, and we have compute power that can start enabling big data. We’ve got communication pathways where if you’ve got a cell phone and a connection, literally anywhere in the world, you can get access to this information.

What does that mean? Because that’s vastly different than living in a world of paper. And so that’s really one of the biggest challenges is one for us to really start allowing ourselves to think outside that box and to allow ourselves permission to change our culture. And then that’s tough because we’ve grown up in a culture where failure is not an option. Well, I would challenge that. We do need to be a little more risky and we do need to be a little more open-minded and flexible in our culture to shift the way we do business from time to time. And I think really the MBSE is one of those situations where we do need to change and move ourselves into using this new paradigm of information and how it works.

Host: What will it take for this to eventually become the standard way NASA does engineering?

Hill: That’s a good question. And you ask different people, they’ll have a different approach to doing it. If you look at where we are, you’ve probably seen those adoption infographics where you got the peak of initiated experience or inflated experience, and then you go through the trough of the disillusionment and eventually crawl up the slope of engagement and alignment, and then you reach the plateau of productivity, right? And that’s typical. I mean, that’s perfectly fine. That’s human nature and that’s OK. I think where we are now is we’re somewhere between the peak of inflated expectations and the slope of enlightenment. But I don’t know if the trough of disillusionment is ahead of us or behind us. It’s kind of early to tell on that.

And again, that’s not meant to sound like a negative statement. It’s just being honest and identifying the potential challenges ahead of us and understanding those in the beginning and try and mitigate any of those effects as we go along this path. Now, the question is how do we get up onto the slope of enlightenment and NASA, if anything, we’re somewhat unique in that we’re not a corporation where whatever the CEO says goes, no questions or you’re fired. That’s not the environment we live in, right? Be it good, bad or indifferent. And we have to acknowledge that.

A lot of it is leadership through influence, leadership through example. I think the administration has done a good job in terms of identifying MBSE as an important capability that they want to invest in such that they stood up an agency level team as part of the Digital Transformation Office, which is another good signal that they want change to take place, to look at what it would take to make this happen. I think that’s good. And I think it’s good that APPEL is very enthusiastically reaching out to us and engaging with us to understand what the requirements are for training. That’s good.

I think a lot of this has to do with dispelling the myth of what it is and what it is not. And that’s education information that’s separate from training, if you will. I think we need to have more opportunities to talk about it at all levels of the workforce, not just senior leadership, not just the grassroot guys who are going to adopt it because it sounds exciting or for whatever reason. But also, the middle managers and the project managers and the system engineering group, we really need to be able to communicate appropriately to the different audiences to really understand what it is, so that we can have the workforce willingly embrace this change. And we have to do this through an education process such that the workforce sees the benefits. And if they can see the benefits of why this is a good thing, a good change to make, a good change in culture to make, then the adoption and the change and the shift will be pretty easy, relatively speaking.

But that in itself as we kind of talked about earlier, that in there lies the challenge of the largest portion of this effort. It’s not a technology problem. It’s not a defining processes problem. It’s really a cultural change challenge that we have in terms of getting us from where we are today to where we are in the future, being fully effective, using the model-based system engineering processes and methodology and being skilled in whatever tools that we need to do as part of all that.

Host: Many thanks to Terry and Jessica for joining us on the podcast. You’ll find their bios along with links to topics discussed on the show, related training courses, and a transcript of today’s episode at APPEL.NASA.gov/podcast.

Terry mentioned APPEL Knowledge Services reaching out to understand training requirements. Our Curriculum team is developing MBSE courses for the NASA technical workforce, and we’ll let you know later this year when the courses are open for registration.

A quick reminder: If you haven’t already, please take a moment and subscribe to the podcast and share it with your friends and colleagues.

As always, thanks for listening to Small Steps, Giant Leaps.