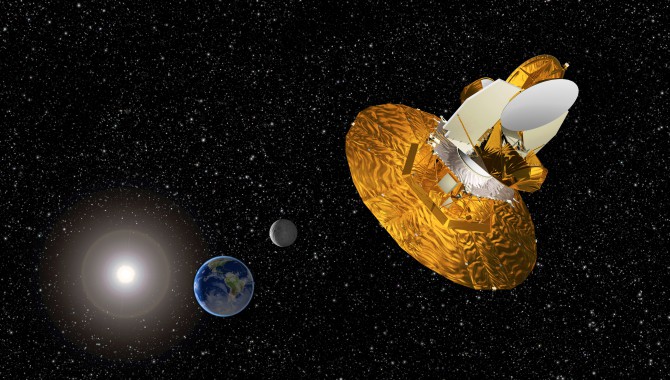

WMAP used the Moon to gain velocity for a slingshot to L2. After 3 phasing loops around the Earth, WMAP flew just behind the orbit of the Moon, three weeks after launch. Using the Moon's gravity, WMAP steals an infinitesimal amount of the Moon's energy to maneuver into the L2 Lagrange point, one million miles (1.5 million km) beyond the Earth. Photo Credit: NASA/WMAP Science Team

ASK: You came to project management from a systems engineering background, correct?

Citrin: That’s right, but at first I started in software, then moved on to be a technical officer on a large development contract, then a manager of software development, and then into systems engineering. I was a lead systems engineer for four years, and then an assistant project manager before becoming project manager on MAP.

ASK: What excites you the most about MAP?

Citrin: The science is tremendously exciting. To study the microwave background left over from the Big Bang is just an incredibly ambitious project. Personally, I find scientific missions much more interesting than technology missions. I like the ones that go for big discoveries. Let’s face it, big discoveries are exciting, and they’re definitely more visible. We’ve had a television crew here, and lots of magazine articles have been written about it.

ASK: When you started at NASA, did you think you’d be leading projects on such big issues?

Citrin: Absolutely not! I didn’t plan my career to get to this point.

ASK: Was there a significant event in your career that stands out more than others that you can point to and say ‘This led me here’?

Citrin: My first project manager was a very dynamic woman. She unofficially adopted me as a mentee and gave me several opportunities to take on responsibility. The project went through several reorganizations, and each time she approached me about taking on more responsibility. I started as one of the most junior people on the project and when I left I was one of the most senior. She also encouraged me to get involved in new things.

ASK: What do you mean she encouraged you to get involved in new things?

Citrin: Well, for one thing I was at a disadvantage because I didn’t have an engineering degree. I came into NASA with a computer science background. Not having an engineering background was a significant piece missing from my training. She encouraged me to take jobs where I could get hardware experience. That was a completely unknown area to me, so it was a huge learning experience, and fun, really fun.

ASK: You said there were many opportunities to take responsibility. Can you describe one?

Citrin: On some of the new missions that were under development there was a need for people. I would even go so far as to say a desperate need. Almost immediately I got put in charge of a whole software effort. I was only working in a maintenance mode for a couple of months when I moved over to the development side. I had little experience so it was hard work, but things like that pay. People know you. If you’re willing to accept the challenge and take responsibility, people respect you for that and the opportunities start to multiply.

ASK: Was it a career decision on your part to take on more responsibility, or is that just your disposition?

Citrin: A bit of both.

ASK: What’s been your biggest challenge as a project manager?

Citrin: Overall, I guess it’s been hard for me to let go of the technical detail. My role as a systems engineer was very technical. I just don’t have time to deal with all that anymore. The schedule is my biggest concern right now; we’re almost at the end of this mission. As a systems engineer I had to confirm schedules, but my primary responsibility was the technical integrity of the mission.

ASK: Is project management a skill you learn mainly by doing?

Citrin: I think it’s very hard to train a project manager to be ready for everything you face. Certainly no one knows everything, and you have to get training.

ASK: What’s the biggest challenge in managing a project the size of MAP?

Citrin: We ask a lot of people, and there are some very stressful periods. We ask people to work late. We ask them to come in on weekends. We talk about balance, but I’ve never seen it consistently achieved. When things get out of control, it’s important to be able to explain why you’re making the decisions you make, and to get feedback from people too. If people know I listen to them, they are going to listen to me.

ASK: Is it possible to be a successful project manager without interpersonal skills?

Citrin: It’s a drawback for sure, but I don’t think it’s impossible. I worked for very good project managers who I thought did not have good people skills, but they had other things going for them. They were extremely intelligent, they were consistent in their approach — it wasn’t always the warmest approach, but you knew what to expect. You don’t have to be best friends with everyone you work with, as long as you understand what’s happening and feel that you’re heard. I think that’s enough.

ASK: How do you strike a balance in managing all the individuals on a project and trying to hold them together as a team?

Citrin: I spend a lot of time on the floor, and in meeting with groups of various people. We have a core leadership team, 8 to 10 senior leaders, and of course a deputy project manager, but I find I get the best information by being on the floor. I know all 120 people who work on this mission. Something I learned from the previous project manager of MAP, Richard Day, when I was his deputy project manager, is one of the best decisions you can make as a project manager is to pick the team yourself. I mean hand pick them. At Goddard we have a matrix organization, and in theory I could say I need three power system guys and they’d supply them. Richard’s approach was to handpick everyone personally, and that way he formed a team that was not only technically excellent but also functioned well as a team.

ASK: Isn’t that a time consuming process?

Citrin: Working all that stuff out at the beginning has made for a much smoother operation over time. He was able to develop a collective mindset right at the beginning. The whole team bought into how we were going to do this mission. As a result, it’s one of the best in-house development teams at Goddard.

ASK: How do you keep people energized on a project that lasts for years?

Citrin: I think it’s healthy to have some turnover on a project. It’s good to get fresh ideas. Some project managers think that people feel betrayed if they don’t get to stay around to the end of the project. I think we need to maintain some amount of coming and going.

ASK: Reflecting on your own experience coming up through NASA, what do you think are the best ways to train younger project managers?

Citrin: I’m a big advocate of experience in different areas. It’s valuable no matter where you end up. If someone’s working in one area, getting better and better at it, that’s not necessarily the best way to get experience in project management. Training also helps fill in the gaps.

ASK: Is it a leap then to say the better project managers are generalists, not specialists?

Citrin: I think the best ones are, but I haven’t done a survey of all. There are other ways to learn too, such as working for someone who is a good project manger. I was lucky to work as Richard’s deputy project manager. It was a great learning experience. I would have never been ready for this, but he’s a great project manager and I learned a terrific amount from him.

ASK: Sometimes you don’t realize the pratfalls of a job until you have to confront them day-to-day. Has there been anything like that for you since you’ve become a project manager?

Citrin: You have to be careful how much emphasis you place on process. I wouldn’t say that process is a pratfall because it has a place, but it can become overemphasized at the expense of the work you do, which is really the science or the engineering. The process should support that work, not the other way around, and I think there’s always a danger of that happening.

ASK: How do you keep that from occurring?

Citrin: By staying focused on the objectives of the mission. These missions tend to be long, shorter than they used to be granted, but four or five years still are a long time. There’s a tendency just to get caught up in the intermediate milestones. With MAP we’ve been able to stay focused because our principal investigator (PI) has been great at explaining to the whole team what we’re doing and how it’s important to the science. We have an all-hands meeting every six months to talk about new developments in the field, so our whole team understands what we’re doing and what’s important to the science.

ASK: Given what you know now as a project manager, are there any experiences you wish turned out differently?

Citrin: When I was the assistant project manager on MAP five years ago, we were trying to develop a different organization structure. We had two very strong line organizations at Goddard. They both developed the same mission operations hardware and IT hardware, but they used different approaches. We said let’s take the best of both and use one ground system; we’ll pick the best people from each group, we’ll architect this system; and I took the lead on it. I said I know ground systems, I know we’ll get reasonable people, and I know we can do this. I worked on it close to eight months and it was hell. The friction was so bad, as well as the lack of cooperation and the unwillingness to make it work, I finally gave up. I said I don’t see how this can work for our mission.

ASK: What did you learn from that experience?

Citrin: Let me add something first. It turned out that higher level management wasn’t ready to give up and said, “Look, let’s do this as a trial effort for six months and then if it still hasn’t worked out, we’ll go back to the old way of doing things.” It turned out that it did work out, and on MAP we have one ground system. Two organizations did get together and we took the best of both. Afterwards I asked myself did it not work out at first because of something I did. I don’t think it was. Rather, I think it just takes time. I got tired and gave up. I should have hung in there a little longer. I think it has changed my behavior. I’m not ready to leave things off if I believe they can work.

ASK: If NASA said to you, we’ll give you whatever tools you need to be a successful project manager, what would those be?

Citrin: I would want to work with other project managers who are considered the best in the field. Maybe not even work with them, but have some direct interaction. I’m talking about intense, hands on experience.