By Mary Chiu

A colleague walked by my office one time as I was conducting a meeting. There were about five or six members of my team present. The colleague, a man who had been with our institution [The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab (APL)] for many years, could not help eavesdropping. He said later it sounded like we were having a raucous argument, and he wondered whether he should stand by the door in case things got out of hand and someone threw a punch

I laughed when he told me this, and he looked even more puzzled. It was business as usual in there I tried to explain. “We were exchanging ideas.” He didn’t get it. That was not the way meetings in our organization were typically conducted.

In the early 90s, my team at APL was building the spacecraft for the NASA Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) project. It wasn’t exactly a new endeavor for APL to be building a spacecraft — we had built plenty before for NASA. But this was a team of mostly young people, highly motivated, extremely intense and dying for the opportunity to be part of something as exciting as a NASA mission. Our energy came into full flower at meetings.

As for the tendency of team members to express oneself, well, loudly, I didn’t only condone this behavior… I encouraged it. I said up front to everyone on the team, ” Meetings are an occasion to voice your opinion and get your views on the table. We want to debate all points of view, and if that means raising your voice to be heard, then you had that permission.” The volume was just a by-product of having that many voices contributing to the discussion. It got loud because people felt they had to raise their voice a notch — if not several notches — to be heard. My objective was just getting people to talk. When decisions have to be made, I believe people must speak up. Living with bad decisions is one thing, but I cannot live with a bad decision because somebody has not come forth with important information. Silence, as far as I’m concerned, is consent.

Because there were so many voices competing, it was easy for an outsider to think our meetings were unstructured. But just because there was a lot of noise didn’t mean they were unstructured meetings. I always had an agenda, and before the meeting I’d send it out. Even if the meetings occurred impromptu, at the beginning of the meeting I’d always say to the effect, “By the end of this meeting we need to do this.” Even though it may have sounded like we were yelling at each other, we liked one another, and we knew each other’s habits — good and bad. We didn’t think of ourselves as yelling at each other. What distressed my colleague who stood outside the door was that he assumed if people were raising their voices at each other they must be fighting. Nobody was fighting. There was enough trust and respect among team members that we understood it was okay to express ourselves in this way. The volume reflected the passion in people’s hearts, the comfort level that existed among us. I’m not saying that passion can only be expressed this way. I’m saying this was one way we expressed ours.

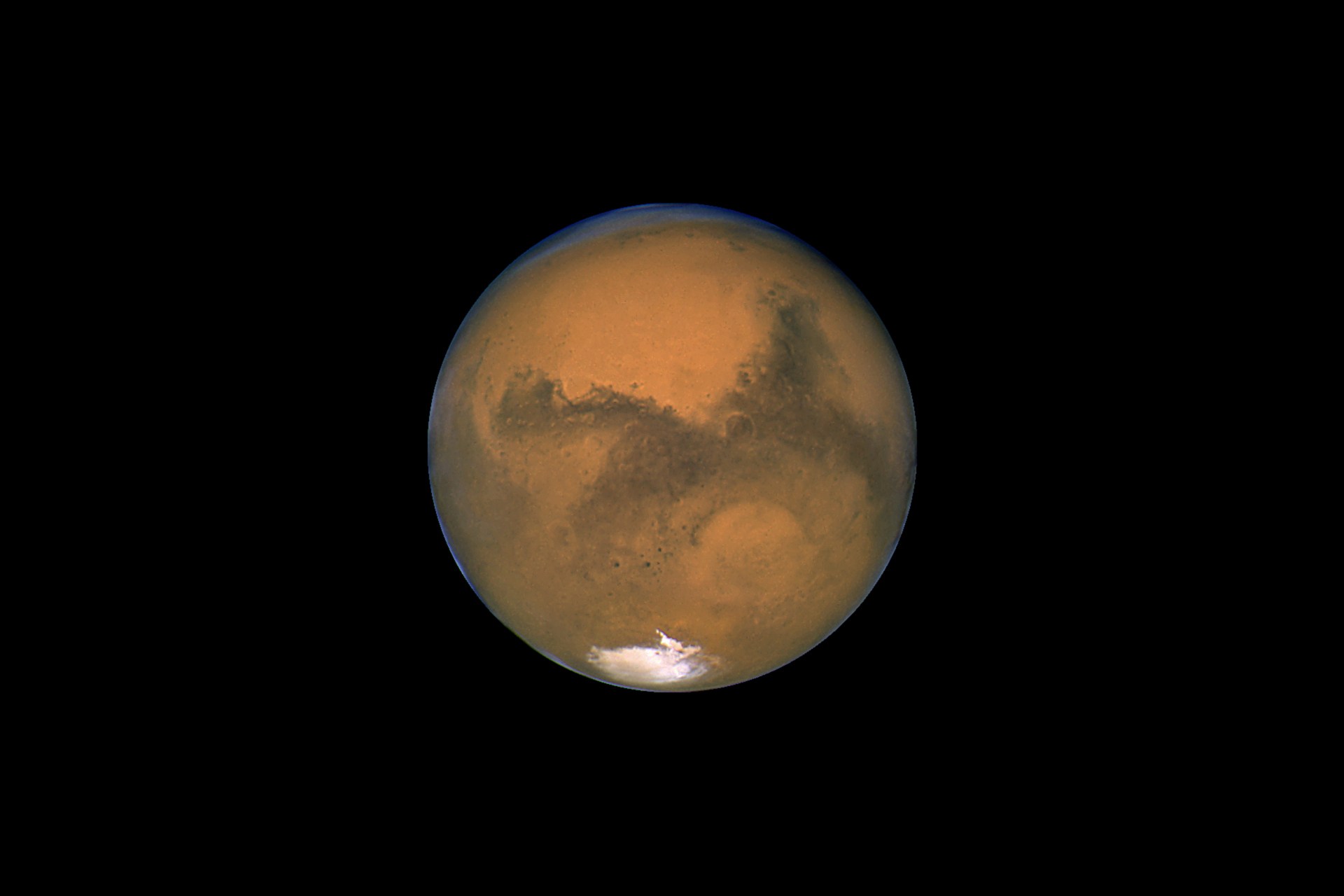

Mary Chiu and her “hot” team from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory built the Advanced Composition Explorer spacecraft for NASA. Instruments on the spacecraft continue to collect data that inform us about what’s happening on our most important star, the Sun.

Understand, we didn’t maintain a fevered pitch throughout the entire meeting. Once we got all the ideas on the table, then we would sort through them in a more orderly fashion to determine how best to approach a specific issue. We tried, and were successful most of the time, to arrive at a consensus. Some people were not always happy with the final decision, and sometimes later they were proven right, but at the end of the meeting people accepted decisions and were willing to move on because the issue had been aired, all points of view discussed. No one came back later on and said, “Well, I had something to say that never got heard.” So often we expect one person to be the leader in a meeting, and that’s usually the project manager, taking the pulse of the group, asking for input — but not really giving up the floor. A lot of times that person just gets what he or she wants. Rare it is then when someone is willing to stand up and play the Devil’s Advocate, which is a critical function on any project team. This is how you test ideas and give them the opportunity to prove their merit.

It was remarkable to me how deeply people were thinking through situations and problems because they were expected to voice their opinions. With everyone expected to talk through an issue from his or her own point of view, assessing the impact of what was up for consideration, I have no doubt we steered clear of many wrong turns we could have made on this project

Our ACE team was a hot group, to invoke the language that is fashionable today, although we never thought of ourselves in those terms. It was just our modus operandi. The tenor of the discussion got loud and volatile at times, but I prefer to think of it as animated, robust, or just plain collaborative.

Tips on How to Lead Productive Hot Meetings

- Limit the number of attendees. Hot meetings generate a comfortable amount of heat for me when the number of attendees is small. At most 5-7 people. With too many people there, you risk creating too much noise. Also, my meetings tend to be the most productive when the attendees represent complementary disciplines.

- Spontaneity should be a high priority. Yes, you want to have an agenda, and certainly you may feel you need to accomplish something specific by the end, but at the same time be open to letting the meeting unfold naturally out of the discussion.

- Listening is important. Encourage everyone at the meeting to listen to what other people are saying. You want people to examine their own ideas as they hear others express theirs.

- For hot meetings to be effective, the group must function as a cohesive team who trusts one another and shares a belief that they are mutually responsible for project results. A group of people who don’t feel dependent upon each other is a committee, not a team.

Search by lesson to find more on:

- Teams

- Meetings