By William H. Gerstenmaier

Any project or program manager will tell you that the key to successful execution lies in mastering a toolkit of basic techniques. No one will be surprised (I hope!) to know that these techniques involve learning how to measure and manipulate the dimensions of cost, schedule, performance or technical capability, and risk. Basically, these are the standard-issue dials that the manager is able to monitor and the knobs that can be tuned to get the hardware out the door, doing what it’s supposed to do, on time and on budget. The good managers can do this reliably, over and over again, for a wide variety of different missions.

A lot of tools and techniques exist to control these four dimensions. Earned value management and similar tools can be used to look at cost and schedule performance and evaluate the project’s chances of coming in on time and on budget. A slew of cost-estimating tools and techniques can do modeling at all stages of project design and implementation. Managers are known to wake up in cold sweats in the middle of the night with visions of S-curves, Gantt charts, and PERT charts dancing in their heads. Risk analysis is a big part of what managers do nowadays, especially for us in space operations, and tools like probabilistic risk assessment help managers get a handle on their risk exposure. These tools let managers do rigorous “what if?” analyses that lead to a good understanding of all the risks facing the project and developing contingency plans to offset those risks.

Obviously, no project will succeed unless the manager understands and thoroughly masters these four dimensions of project management. They are the bread and butter of the profession. However, as projects and programs get bigger, more complex, and more visible, the manager is forced to realize that understanding these four dimensions represents a necessary, but not sufficient, foundation for success. There is a “fifth dimension” of project and program management: politics. Now, by “politics” I mean the set of expectations and perceptions that people inside and outside the organization develop, both in their own minds and collectively, about what the project is really all about, and the methods by which they seek to influence the process.

Politics in this context are forces not directly related to cost, schedule, and performance and that cannot be controlled using the classical tools of project and program management. But because your project or program is embedded within the context of a larger effort, these political forces can play a big role in overall mission success. Your project or program may be part of the vision of the company or the government, or be aligned with the corporate goals of skills development not directly related to the publicly stated technical goals. Every stakeholder (literally, anyone who has an interest in an enterprise or outcome) may have different, even conflicting, reasons for pursuing a project.

Expectations and perceptions about the project develop even before the project begins. These perceptions may have limited basis in actual fact and can come from media reports, other external sources, or even from overzealous proponents within the project itself. The media in particular is often structured to respond more readily to something new or different, and differences in expectations, perceptions, and the reality on the shop floor or in mission control can make great news. For example, an external stakeholder can perceive that your project may be “easy” or “hard,” depending upon his or her comparison of this project with similar projects in the past. This expectation may be either accurate or inaccurate, but it is very real in the mind of the evaluator and can be difficult, if not impossible, to change. Space flight projects, for instance, are often expected to be like aircraft projects, even though the amount of energy that needs to be controlled for space flight is an order of magnitude higher. And while NASA is expected to deliver excellent technical results, the perception of NASA’s ability to control cost and schedule performance is often quite poor.

Because these political issues of expectations are so important, care must be exercised in managing these expectations and perceptions in the early stages of the project. For example, the early justifications for the Space Shuttle in the 1970s assumed that the system would operate like an airline, flying up to sixty times per year and at a cost of $100 per pound of payload, thereby making all other launch vehicles obsolete. Obviously, even in our best years when commercial operations were heavily subsidized by the government, the shuttle ended up pushing far too much technology in terms of thermal protection, engine performance, materials science, etc., to ever realize these sorts of mission tempos. Because the shuttle was originally pitched as a low-cost space “truck,” its incredible capabilities and its role as a versatile work platform are often discounted or ignored by skeptical stakeholders. Similarly, the International Space Station was going to be a “world-class” research facility, while the actual design and assembly of this — the largest complex ever flown in space — was pitched as easy and inexpensive. This pitch completely understated the fact that, while the basic technology used in the construction of the space station was well understood, the sheer scale of the assembly challenge and the complexities of managing a fully international project were greatly underappreciated by many stakeholders. These kinds of misleading initial expectations can haunt a project throughout its life and make the job of a project manager extremely difficult.

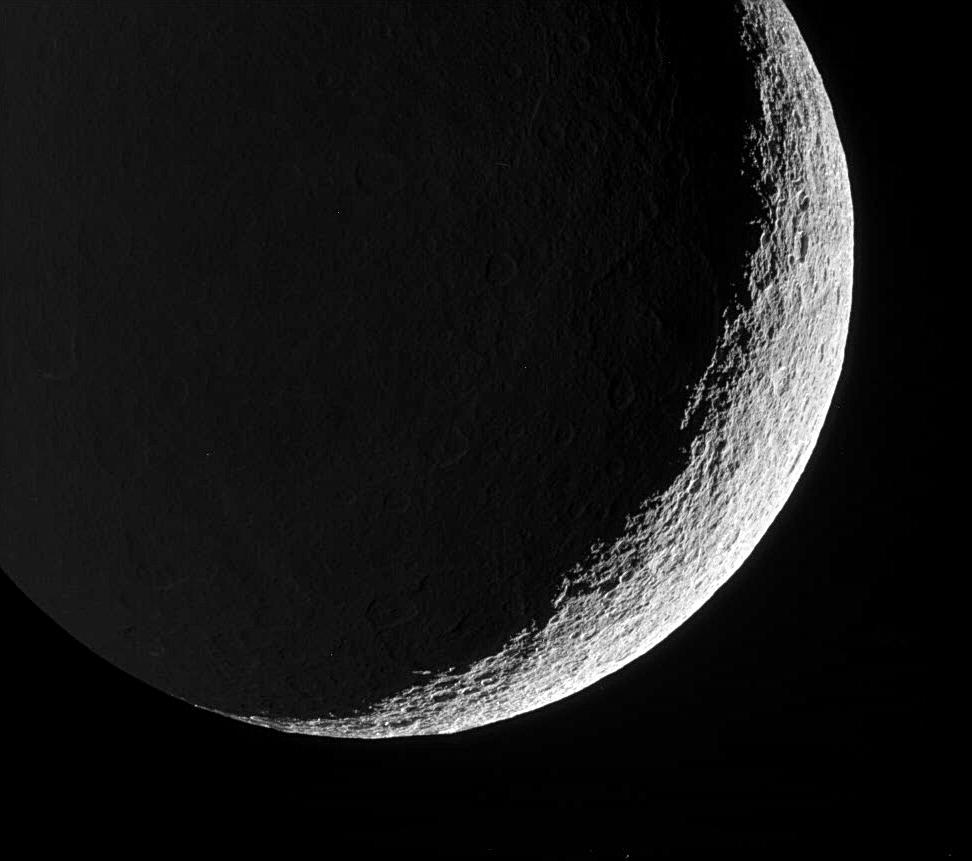

Big projects and programs, of course, mean more stakeholders. The politically astute manager will have an almost instinctive grasp of what this growing circle of stakeholders will find most compelling about the project and how to use that innate sense of excitement to build support for the mission. Think about some of the biggest space successes in recent history: the Hubble Space Telescope; the rovers Spirit and Opportunity on Mars; Stardust; Cassini-Huygens. Not only were these projects hugely successful from a technical standpoint, but they have also become widely perceivedas being hugely successful. it’s tough to say exactly what it is about a successful technical project that will resonate with people. Maybe it was the fact that Hubble returned pictures in visible light rather than some other wavelength. Maybe it was bringing primordial samples of the sun back to Earth for people to actually touch. Maybe it’s the cool factor of driving around the deserts of another planet, or hearing the wind whistle past as a probe screams through the atmosphere of a distant moon. One way or another, every successful effort has involved nurturing the kinds of personal connections between stakeholders and the project that build long-term support. Managing the biggest, most visible projects means always being aware of why the project is important, why people should or would care, and what the manager can do to share their own sense of excitement as broadly and effectively as possible.

Perceptions can change over time as the benefits of a project become clearer. This was certainly the case in the Lewis and Clark expedition, which ended up costing more than ten times its initial Congressional appropriation. That expedition, or the Hubble Space Telescope in our own time, proves that astute managers can overcome a project’s early problems ifthe fundamentals of good project and program management are observed and mission success trumps the initial set of negative perceptions. By being aware of the effect that external stakeholders’ negative perceptions can have on mission execution, the politically savvy project manager can avoid inadvertently reinforcing these perceptions and better communicate with target audiences.

The problem with trying to manage the political dimension to minimize the negative effects on mission success is that communication technology does not stand still. The Internet, in particular, is changing the way big projects are perceived and evaluated by external stakeholders and the public in two ways: (1) by providing anyone with a computer a huge volume of data upon which to form opinions and (2) by providing alternative avenues for well-intentioned personnel within a project to “leak” information outside the normal internal channels of communication. Leaks, in particular, can turn a very technical, nuanced discussion within the community into a public debate where people with vastly differing agendas are given the opportunity to pursue diverging interests at the expense of intelligent and logical decision making. Even traditional news sources are being radically changed by Web logs or “blogs.” While traditional news sources typically have a number of policies that address issues like source citation, collaboration, and editorial review, blogs are not so restricted. Information on such blogs can therefore be put out very quickly, but the quality and accuracy of that information can be proportionally diminished.

The immediate reaction of the manager might be to attempt to intercept and stop these external lines of communication from taking place. I think this approach is wrong, both on practical and philosophical grounds. Attempting to impose draconian communication requirements on a team is at best an example of attacking the symptomswhile leaving the underlyingcauseunaddressed; at worst, heavy-handed tactics demonstrate better than anything else that there are systemic communication problems within the project that will eventually lead to mission failure. Instead, rapid advances in alternative communication avenues mean that managers should work harder than ever to improve the internal lines of communication within their organizations. Employees must trust that they will quickly get the best information on decisions from their own organization and managers. This trust must be built on strong and mutually respected lines of communication both within the organization and between the organization and the outside world.

Successful organizations understand that all stakeholders, internal and external, have a legitimate interest in project information. These demands mean that managers operating in the fifth dimension must become communication experts adept at tailoring style and context for specific audiences. For example, an engineering team demands precision and technical accuracy to come up with the best technical decisions possible, but a Congressional staffer who is responsible for overseeing literally dozens of different federal agencies naturally has very different data requirements. Understanding the role of communication inside and outside the engineering organization therefore becomes thesine qua nonfor managers of highly visible projects operating in the fifth dimension.

Just as an athlete cannot make it to the Olympics without extraordinary physical ability, a good manager must master the first four dimensions of project and program management to be successful. However, mastering the tools and techniques of cost, schedule, performance, and risk management is not enough to guarantee the gold medal. To win the gold, Olympians must possess other characteristics that give them a slight edge over the competition. Being aware of the fifth dimension of project and program management and learning to operate effectively in this dimension can lead you to become a gold medal manager.