Don Cohen, Managing Editor

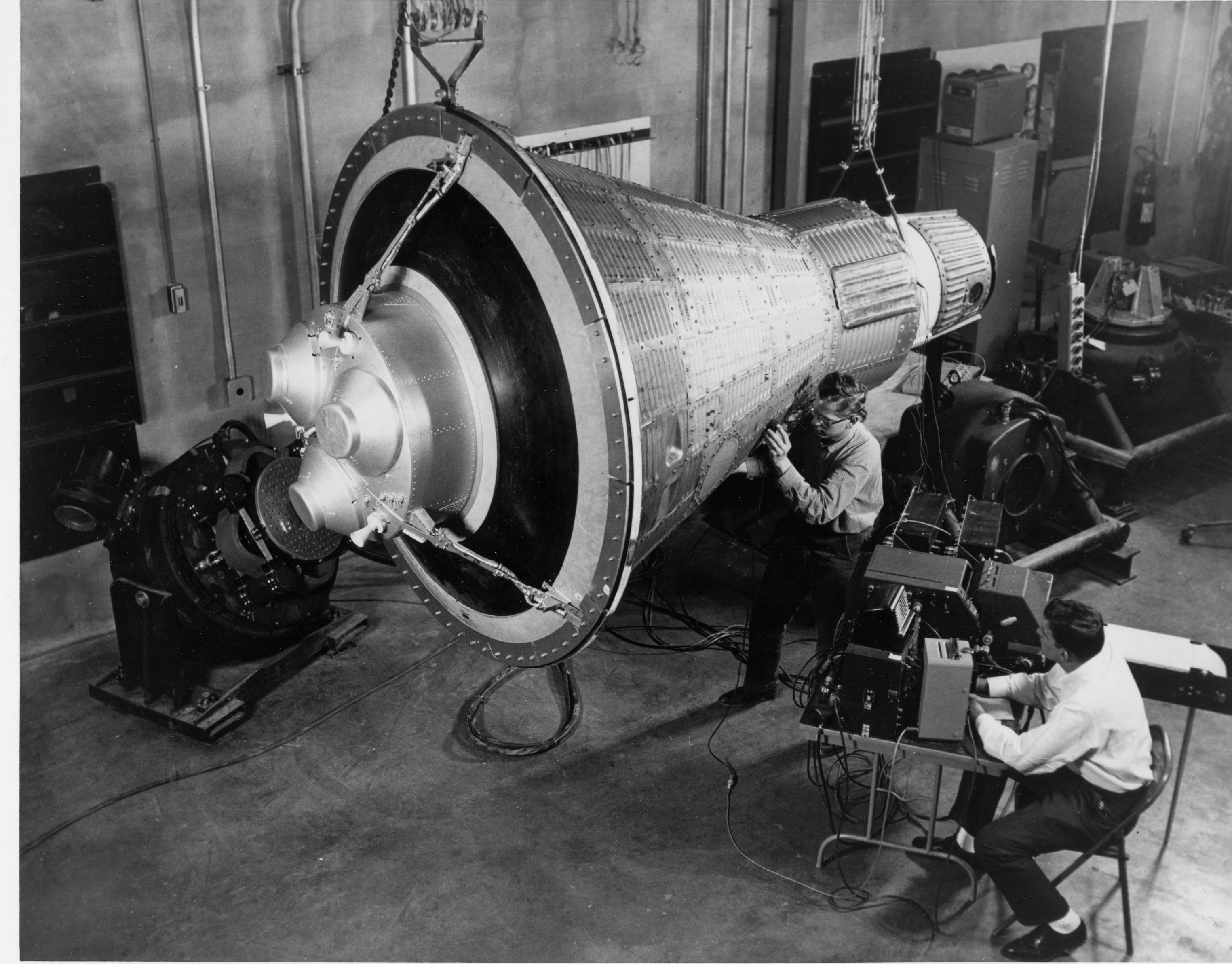

A casual observer of NASA’s accomplishments from Mercury and Apollo to the Space Shuttle, space telescopes, and interplanetary robotic missions would probably guess that those achievements depended on two things: technical knowledge and money.  Those are essential, of course. But the ability to manage that complex, innovative work—to plan, guide, and evaluate efforts of many people in many places—has been equally important. Landing a man on the Moon required the combined knowledge and skills of several hundred thousand individuals working for tens of thousands of contractors and universities. It was as much an organizational triumph as a technical one.

Those are essential, of course. But the ability to manage that complex, innovative work—to plan, guide, and evaluate efforts of many people in many places—has been equally important. Landing a man on the Moon required the combined knowledge and skills of several hundred thousand individuals working for tens of thousands of contractors and universities. It was as much an organizational triumph as a technical one.

The Agency’s new mission—to build an outpost on the Moon and fly humans to Mars—is in many ways more ambitious than Apollo. It will demand decades of outstanding cooperative work from all ten NASA centers and many contractors. It too will be a managerial challenge of daunting complexity and scope. As NASA Administrator Michael Griffin notes in his column on the role of governance, it “will require as much ingenuity, hard work, and sustained commitment as NASA has ever brought to bear.” This special issue of ASK is devoted to the Agency’s efforts to develop the organizational structures, policies, procedures, and practices needed to organize and support that work and commitment.

A number of articles focus directly on the new NASA Procedural Requirement documents that establish the consistent processes and clear roles and responsibilities needed to carry out and coordinate the programs and projects that will turn the Vision for Space Exploration into reality. Chief Engineer Chris Scolese and Associate Administrator Rex Geveden emphasize the importance of the clarity and consistency of the procedures, especially as they relate to decision making and the balance between project authority and engineering authority.

Geveden also talks about the importance of a relentless focus on the mission, and Ed Hoffman describes the kinds of career-long training and education that the new vision will require. The framers of the procedural documents have striven to make them practical tools that support the mission, not bureaucratic abstractions of how programs and projects should be carried out. “Documented Experience” and Garry Lyles’ “Enabling Exploration” describe some of their efforts to incorporate knowledge developed through long experience in the requirements and to test them against the reality of actual work. Bryan O’Connor (“Safety and Mission Assurance: Independent Yet Engaged”) and Scott Pace (“Program Analysis and Evaluation: Clarity and Independence for the New Mission”) describe how their organizations identify potential risks and problems in NASA programs but also look for solutions. Their aim, too, is to help accomplish the mission, not put roadblocks in the way.

Real-life experience is always more varied and surprising than even the most sophisticated plans and procedures can describe or predict. Rob Manning’s conversation about the Mars programs he has worked on make that clear, and the historical perspectives provided by C. Howard Robins, Jr., and Roger Launius point out some of the continuing challenges of managing complex projects. Howard McCurdy argues that NASA must continue to innovate, not only in creating its spacecraft and launch vehicles but by finding new ways to work efficiently and well. The articles in this issue show how much thoughtful work has been done to ready NASA for the new era of space exploration, but they also make clear that we are only at the beginning of a long, demanding, and exciting journey.