By Laurence Prusak

Knowledge management as a discipline and practice has now been with us for about twenty years and shows no sign of disappearing into that distant land where old fads and fashions go.  It may change its name and some of its practices, but it continues to thrive because organizations need to develop and use knowledge effectively to deal with increasing uncertainty in their environments. But what of individuals? Don’t they too live in very uncertain times, with tectonic shifts in the global economy and in the relations between employers and employees? Don’t they need to manage their knowledge?

It may change its name and some of its practices, but it continues to thrive because organizations need to develop and use knowledge effectively to deal with increasing uncertainty in their environments. But what of individuals? Don’t they too live in very uncertain times, with tectonic shifts in the global economy and in the relations between employers and employees? Don’t they need to manage their knowledge?

The answer everyone gives (at least everyone I poll) is, “Of course, I manage my own knowledge. I wouldn’t get anywhere if I didn’t!” Yet when I ask them how they do it—what specific activities they undertake—I usually get a blank stare and a response that goes somewhat like, “Well, I try to read on the plane,” or, “Every year I go to a conference, or every year when I have the budget.” Pretty slim pickings for what is perceived to be an essential activity.

So what can one do to manage one’s knowledge? What can an individual learn from what organizations have been doing for the past few decades? Here are some practices to ponder based on my own observations and consulting as to what works in this field.

Scanning and adopting: Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate in economics, observed that one of the most important things for any organization to do is “scan globally and adapt locally.” This lesson is also pertinent for individuals. One needs to continuously search for new ideas, products, even new dreams and visions, to keep abreast of the vibrant and growing global marketplace of ideas, a market that has been made both more competitive and more efficient by the Internet. If you don’t, you can be sure someone else will, and you will lose a step in keeping your own knowledge up to date.

Vetting and filtering: Even if you spend much of your limited time scanning and searching for new ideas, you still need to learn how to evaluate what you are taking in. This vital skill is seldom taught in school. How do you judge how true or how useful what you are reading is? Can you “take it to the bank”? Do you have the tools to discern the valuable parts of the fire hose of stuff coming from the Web? With so many firms, journalists, publicists, and consultants pushing products, how can you judge what really matters? It’s possible to distinguish good from bad, but it takes time and effort.

Networking: Many of us get our new ideas from colleagues, friends, co-workers, and others in the varied networks we belong to. This is fine. Faceto- face (or terminal-to-terminal) communication with those we know and trust has always been a potent source of ideas and always will be. Here too, though, think through how you go about it. Are you yourself trustworthy? That is, do you provide valuable knowledge when someone in your network asks for help? Do you make real contributions to your network or just take what you need? One of the least-mentioned subjects in the many books on networking is the need to invest in your network, putting in time and resources to strengthen the network’s density, content, and reach.

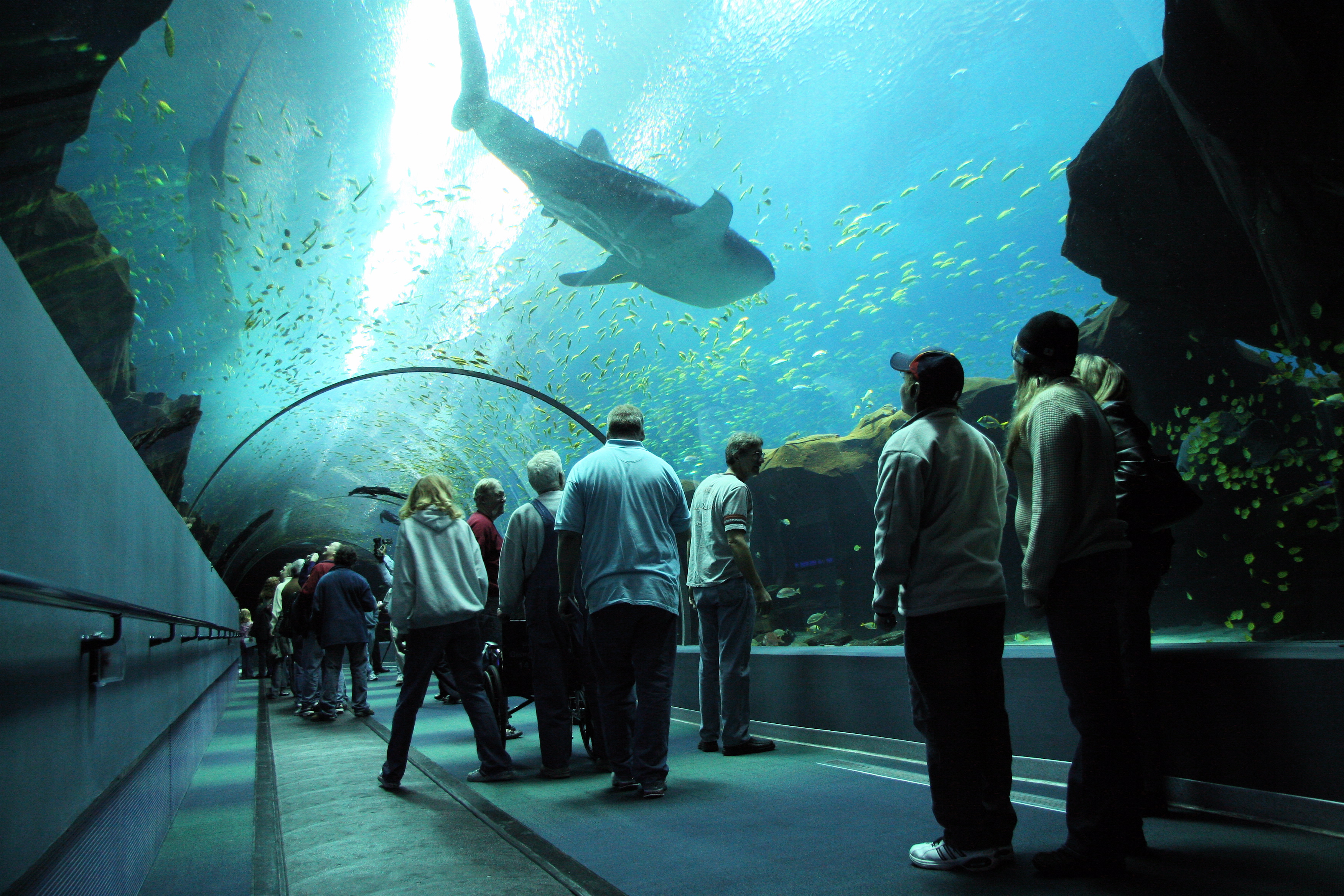

Getting out of your office: This might sound a bit banal and obvious but it is important to say nonetheless. What you know depends on where you are. Stay in your office all the time and what you know will be the walls and windows surrounding you. Yes, you have your trusty computer and access to all the world’s information, but information isn’t knowledge. Think of the difference between reading about a country (information) and spending time there (knowledge). And new ideas are more than words on a screen. They include passion and other emotions that can only be communicated by being there. There is no substitute for getting out and going someplace to really “get it”—to deeply and usefully understand a new idea, problem, situation, or opportunity.

As you can see by now, a key concept in this piece is investment. Knowledge is expensive to obtain. If you are going to manage your own knowledge assets, you will have to spend some of your scarce resources—especially of time and perhaps money. There just isn’t any shortcut to knowledge or technical marvel that makes learning fast and easy. Genuinely knowing a technology, a market, a country, a firm, a set of propositions, or a concept takes investments in attention, travel, and care. Obtaining new knowledge is expensive, but a lot of old knowledge loses value over time. My advice is to keep investing.