Recent college grads who work for NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., successfully launched a sounding rocket 120 kilometers (75 miles) above Earth's surface on Monday, Dec. 6, from the U.S. Army's White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. Image credit: White Sands Missile Range

In November 2006, then-NASA Chief Engineer Chris Scolese brought together an advisory group of aerospace veterans to think about creative ways of giving young NASA employees the skills they will need to lead future projects and programs. Gus Guastaferro, an invited guest of this Management Operations Working Group, suggested developing a hands-on project that would give young engineers and scientists the opportunity to take a small mission from concept to launch to post-flight analysis.

Just over two years later, NASA centers received an invitation to submit proposals for the first Hands-On Project Experience (HOPE) training opportunity. Five centers responded with project ideas. The winning plan, to improve terrain-relative navigation by collecting ground imagery during a sounding-rocket flight, came from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). In the spring of 2009, a group of young JPLers led by project manager Don Heyer got to work on what they called the Terrain-Relative Navigation and Employee Development (TRaiNED) project.

Creating HOPE

Guastaferro’s conviction that actual work experience provides uniquely valuable learning and his sense of what a hands-on learning project would look like came from his early days at Langley Research Center in the late fifties and early sixties. To develop the skills needed to add space exploration to the center’s aeronautical work, Langley had members of its newly formed Space Task Group plan and carry out small rocket launches from Wallops Island. That experience gave Chris Kraft, Robert Gilruth, and other Apollo-era leaders knowledge of the technology and management of space programs that became the foundation of their achievements at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, later renamed Johnson Space Center. Guastaferro notes, “In my own career, I pushed hard to become the launch director of the small Scout launch vehicle at the Western Test Range in 1966 to get my own hands-on experience. My decision to do that was based on the early days in the Space Task Group at Langley and the experience set the stage for my assignment to Viking in 1968.”

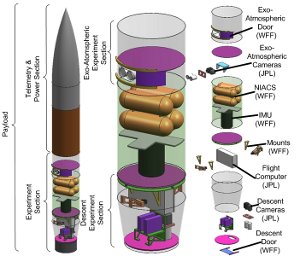

Schematic of the Terrain-Relative Navigation and Employee Development project payload.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL

All NASA employees learn from experience, but when the learning comes from playing relatively small roles in long, complex projects, it can take many years to develop the repertoire of skills needed to lead projects and programs. The projects in the program that grew out of Scolese’s request would last approximately one year, allowing participants to experience all phases of a spaceflight project in a concentrated form and much sooner than they normally would in the course of their careers. The brief missions would give them valuable perspective on how project elements and stages meshed into a whole to achieve the aims of the mission.

Early on, the advisory group envisioned the Academy of Program/Project and Engineering Leadership (APPEL) as the sole sponsor of HOPE. It seemed a natural choice, given that organization’s responsibility for learning and development. Scolese believed, though, that having the Science Mission Directorate (SMD) become a co-sponsor would increase the value of the initiative. In addition to sharing funding responsibility, SMD would give HOPE added legitimacy by ensuring that the projects would have a genuine scientific goal and not be “merely” training exercises. Brad Perry was designated SMD lead and given responsibility to ensure that HOPE projects would make a scientific or technical contribution to one of SMD’s four divisions: planetary science, Earth science, astrophysics, or heliophysics. Perry said, “I am excited to be involved with HOPE and the opportunity it affords to develop future NASA leaders through practical ‘hands-on’ experience.”

Wallops was recruited to provide launch services for the projects. A budget of $800,000 per project was established (with the understanding that centers would be free to add funding). By the end of 2008, the team developed a training opportunity announcement soliciting proposals for the first HOPE project. The document specified the two main goals of the program:

- To provide hands-on experience on an Earth or space science flight project to enhance the technical, leadership, and project skills for the selected NASA in-house project team.

- To fly a sounding-rocket science payload, which will have a useful purpose for the SMD by either providing new or complementary science data for one of the four SMD science divisions or by developing capabilities in support of SMD science objectives.

Evaluating the Proposals

The proposals received from five NASA centers offered a wide range of investigative ideas. Three separate groups reviewed the submissions. One, led by Guastaferro, evaluated their training merit. Paul Hertz, SMD’s chief scientist, led the panel judging their scientific merit. The group led by Carlos Liceaga assessed the quality of their technical management—the likelihood that the proposed plans and resources would accomplish the project aims on time and on budget.

Results from the three panels were merged to arrive at a final judgment. The JPL terrain-relative navigation proposal was the winner. Because the project built on a previous sounding-rocket mission, it promised to accomplish its scientific goals while limiting its scope by reusing much of the technology from that earlier flight. The JPL submission was also strengthened by the existence of an early-career-hire development program at the center called Phaeton. The two programs were a natural fit. Phaeton (which will be the subject of a future ASK article) provided the mentoring resources needed to make HOPE successful.

The First HOPE Project Begins

A Mission Initiation Conference at Wallops Island in May 2009 officially launched the project. At that meeting, the Wallops team presented their plan and Wallops personnel described their sounding-rocket services. To give participants the benefit of authentic project experience, the TRaiNED initiative will follow standard NASA procedural requirements. A Standing Review Board assembled for the project will see the team through milestones including a system requirements review (held in early July), preliminary design and critical design reviews, and a mission readiness review. The project launch is scheduled for June 2010. Several months into the work, project manager Heyer said, “The TRaiNED project is giving a group of early-career hires an opportunity to learn firsthand how a flight project is implemented, from formulation through flight.”

The main goals of the project are of course accelerated learning from the promising early-career hires at JPL and scientific results that can contribute to other NASA programs. But APPEL and SMD also hope to learn from the experience. They are observing and evaluating the TRaiNED experience with an eye to improving future HOPE projects. Whatever shape NASA’s future missions take, they will require the highest possible level of technical and managerial expertise. So Scolese’s call for new and better ways to develop the skills and knowledge of young NASA engineers and scientists to carry out future programs will remain important. HOPE is one promising response to that call.