McAuliffe undergoing pre-flight training experiences weightlessness during a KC-135 "vomit comet" flight. Credit: NASA

Vol. 4, Issue 1

On the 25th anniversary of the Challenger accident, a story by Bryan O’Connor offers a powerful reflection on the dangers of organizational silence.

[Editor’s note: The following is a transcript of a talk by Bryan O’Connor, NASA Chief Safety and Mission Assurance Officer, at Goddard Space Flight Center on July 30, 2009. O’Connor delivered his remarks at an event hosted by Goddard Chief Knowledge Officer Dr. Ed Rogers on the subject of organizational silence.]

When I first heard about this topic [of organizational silence], the very first memory that came to me was the flood of emotions after the Challenger accident. I lost some good friends in that accident. It had happened just two missions after I had flown my first spaceflight, so it touched me quite a bit there. I was already assigned to another mission, and that mission got delayed indefinitely and then later canceled as we went through post-flight/return to flight activities. Now I had lost friends before in aircraft accidents, but I had never had the same kind of feelings after those as I did after Challenger. And it wasn’t just because I lost friends. There was another thing that entered the picture, and that was in spite of the fact that I didn’t really have a job at NASA that put me in the accountability chain of command for safety on space shuttle, the fact is that I didn’t know, like everybody else, I was responsible to some degree for safety—to the extent that I had any authority, to the extent that I had knowledge. I certainly had a responsibility to speak up if I didn’t understand something. I kind of knew all of those things and I felt a little bit guilty. In fact, I felt very guilty. That was an overwhelming feeling that I had that I hadn’t had in previous cases.

The reason I felt guilty, I believe—and I’ve thought about it a lot since then—was that I could remember times when I was sitting in a meeting listening to a discussion in an all-pilot’s meeting, maybe even over in a programmatic meeting, a change board or something—where I was sitting in the audience, where I thought and sometimes claimed to know that two people were talking past each other. And I didn’t say anything about it. I just kind of let it happen. I thought, “Well, these people know what they’re doing. The Space Shuttle Program comes from all this learning from Apollo. These folks can’t really make mistakes because they have already done that, they learn from them and…this thing is being developed as something that will be pretty much an airline-like operation very soon here.”

The U.S. flag in front of JSC’s project management building flies at half-mast in memory of the STS 51-L crewmembers who lost their lives in the Challenger accident. Photo Credit: NASA/Johnson Space Center

There were things about that whole concept that I didn’t really get, I didn’t understand. I remember having a discussion with T.K. Mattingly, who was training for STS-4, which as you remember, was going to be the last “test flight” for space shuttle and after that we were going to be “operational”. STS-5 and beyond was operational. So operational, in fact, that they were going to put the pins in the ejection seats so that the crew couldn’t use them on STS-5. And they weren’t going to have ejection seats after that.

This, to me, was a huge leap of faith from my prior experience. I had come from an acquisition background where it took a couple thousand flights to get something to where it was IOC (initial operating capability), and then maybe another several hundred to full operational capability. And in DOD (Department of Defense) terms, IOC and FOC mean it’s time to give it to the ultimate operator: we’re done with all the testing, and it’s time to go into the “operational phase” and give it to the operator to go use in the field. That’s what those terms meant to me.

I saw us using terms like “we’re going to be operational on Flight Five” on what looked like to me like a more complicated machine and operation than anything I’d ever been dealing with. And I asked Mattingly about it, and he said, “Don’t worry about all that stuff, that’s just rhetoric up in Washington. This thing will be in a test mode for a hundred flights.” He told me that before STS-4. That was a little bit more comfortable to me because I thought, OK, I got it. I’m now in an area where there is a political and public affairs activity that goes on that I can’t allow to interfere with my engineering and technical job. Yeah, I know they’re taking the seats out, and I know we’re going to put four or five people in these things, and there’s people talking about flying reporters, book writers, teachers, and people who are not professional test-folks in a test environment, but I’ve got to treat that last part as just more rhetoric and that probably won’t happen. Our people really understand the risks here.

Of course, there was a big awakening for all of us after Challenger. Those were thoughts that I had, and I didn’t talk a whole lot about them. They just were just a way for me of rationalizing what was going on. But we didn’t really talk much about that. We went the first twenty-some-odd flights—and this conversation between Mattingly and me was quite rare. It was almost as if we all know that but…let’s just press on and do our business. When the Challenger accident happened, the accident board beat us up, the public wrote articles about how we were fooling ourselves about how operational we were, [and] we had totally under-estimated the risk of this operation. All those things that I had sensed at some point early on were now being blasted at us by the public. The same public that was buying our discussion about how safe this was, was now beating us up for how we had fooled ourselves. That was part of why I was feeling different after this accident.

In previous accidents, we weren’t kidding ourselves about the risks, in any environment I had ever operated in. Flight test environment, training for combat, whatever, we kind of knew where we were, what the risks were, and yeah, bad things happen, that’s too bad and we’ve got to learn from it. But we didn’t come out of that thinking, “Wow, we really underestimated the risk there,” like we did after Challenger. That, I think, was part of why I felt so bad. And how this feeling bad sort of registered was [the realization that] I’m never going to sit in a meeting and allow two people to talk past each other and not say something myself. Or at least talk to them in a hallway afterward. I just can’t do that anymore. I don’t have the right to do that. That was something I carried with me from then on.

There’s a dilemma that goes with that, though, because that’s an intimidating environment. When do you speak up and say, “I think you guys missed the point here?” I’m sitting in the peanut gallery and I’m not even cognizant of the technical issue here, it’s just a matter of…trying to follow the logic and it doesn’t make sense to me. I may not really know the details of the engineering discussion, but I can tell when two people are thinking they are agreeing on something and they didn’t say the same thing. At least I know that. To that extent I am accountable because at least I know that, and I can say something about that. And I hadn’t for five years. I sat and listened to that and I thought, ‘Wow, sounds like those guys talked past each other, but I guess that’s OK.” It’s not OK.

This was the big awakening for me after Challenger. I don’t have the right to be quiet when I think something is wrong.

Above: Crew members of mission STS-51-L stand in the White Room at Pad 39B following the end of the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test. From left to right they are: Teacher in Space participant Christa McAuliffe, Payload Specialist Gregory Jarvis, Mission Specialist Judy Resnik, Commander Dick Scobee, Mission Specialist Ronald McNair, Pilot Michael Smith, and Mission Specialist Ellison Onizuka. Photo Credit: NASA

Now, what do you do about that? You could rapidly become a pain in the butt if you operated on every instinct. Even if you batted as well as Ted Williams and got four out of ten things right, six times out of ten you’re a nuisance by speaking up and interrupting the flow of discussion and slowing things down and so on. That’s real life. You have to take that into account. We can all say we all ought to speak up if we feel bad about something, walk out of here, and say, “Right, I’m going to do that.” But in real life you’ve got to think about the environment you’re really in. Do we really need to slow this thing down on this count? How badly do I actually feel about this? Is this something I can talk one-on-one in the hallway with? You’ve got to think about those things too, and that makes it more difficult sometimes.

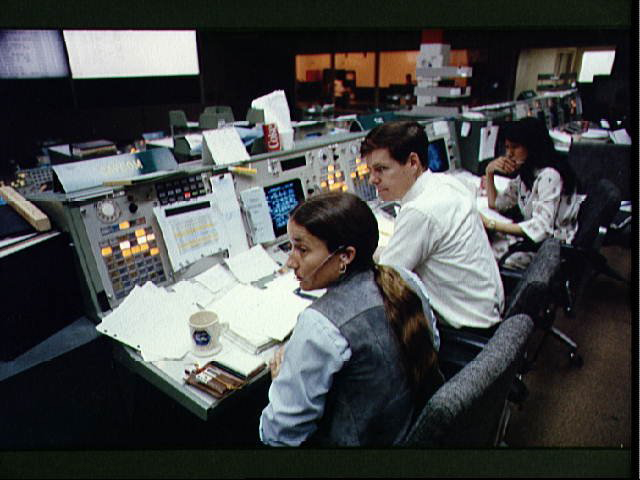

Part of that awakening registered itself about three years after Challenger, when I was involved in the simulations out at Ames Research Center where they have this big vertical motion machine….It can get up about 80 feet above the ground and 60 or 70 feet left and right, 6 degrees of motion. We used it for landing simulations so we could try out new gains on the flight control system for landing and rollout, nose-wheel steering algorithms that we were trying to change to make it so that the space shuttle would be able to survive a blown tire on landing. [That was] one of the many things we were doing after Return to Flight. I was involved in that. I came back [to Washington] and I was sitting in a meeting where this was a topic of discussion, and Arnie Aldrich was program manager and he was in charge of this meeting. It was at a change board, and when this particular issue had come up, I was the guy they sent from the crew office to go sit and represent the crew office. I was sitting in there, but I’m sitting behind the chairman, not at the table. He went through everything, and they were talking about how they needed to make a change, and it was probably going to cost some money, and this will be to the benefit of the safety for the program. Arnie, somehow, was aware that I had walked in—I don’t know how because I didn’t say anything—but he turned around and said, “Now you just came back from Ames, right and flew the simulator?”

“Yes sir, I did.”

“I want you to tell us about that.”

I never would have volunteered what I had learned in that simulator in that meeting. I didn’t have the nerve to break in, but I certainly had relevant information. The fact that the institution was such that they pulled something from me helped me with part of my dilemma about speaking up. It suggested that sometimes speaking up is not something that you can just tell every person that they have that right or that responsibility. It’s something that you have to put into your organizational construct. You have to have a system that actually pulls a little bit. If you don’t do that, you’re going to miss a lot. Speaking up is not just about proactively interrupting meetings or raising your hand or throwing down the red flag. Those all have their place, but it’s also about having a system in place that draws out relevant information, that gives people permission to speak, that points at folks and says, “What do you think?” When Arnie Aldrich did that, I thought, “That is tremendous leadership he just showed here,” because I did have some relevant information that probably would not have gotten into this meeting had he not asked for it.

It showed two things to me. One, I’m still not there yet on when to volunteer. But two, it’s really important to have an institutional component to this business of speaking up.

Sharon Christa McAuliffe received a preview of microgravity during a special flight aboard NASA’s KC-135 “zero gravity” aircraft. A special parabolic pattern flown by the aircraft provides shore periods of weightlessness. These flights are often nicknamed the “vomit comet” because of the nausea that is often induced. McAuliffe represented the Teacher in Space Project aboard the STS 51-L/Challenger when it exploded during take-off on January 28, 1986 and claimed the lives of the crewmembers.

Featured Photo Credit: NASA