By Naoki Ogiwara

In Europe and Japan, “Future Centers” feature spaces designed to enhance creative thinking.

Organizations—no matter what industry they belong to—are now facing more complex social, technological, political, and environmental challenges than in the past. To tackle such issues, some European and Japanese organizations have created unique physical spaces called “Future Centers.” Some of them are producing appreciable results.

Tax and Customs Administration Creativity

At “The Shipyard,” a number of officers use the room named “The Brain” when they brainstorm. The room is carefully designed to stimulate users to come up with many wild ideas: walls as whiteboards, lighting patterns, intentionally not-very-comfortable stools (comfortable chairs make people too relaxed for brainstorming, according to them), and an out-of-sight door (doors being points where somebody might intrude and break concentration). A room called “The Silence,” in contrast, is serene and hushed, with layers of curtains that shut out any sound and with comfortable cushions—one can even lie on them—and without visible doors or windows. This room is not for discussions but for calm dialogue and reflection.

The Shipyard is owned and operated by the Dutch Tax and Customs Administration. It was built in 2004 by renovating a historic building for the purpose of leveraging the intellectual capital of the agency and enhancing the creativity of its officers. Why is creativity so emphasized at the Tax and Customs Administration? According to Ernst de Lange, founder and innovator of The Shipyard, there is a strong need to leverage officers’ brains: “Tax evaders and frauds are very creative. To collect money, or seize assets from them, we simply need to be more creative. Effective education for taxpayers and future taxpayers, utilization of intuition in the revenue office’s work—there are so many fields where we need to bring out the potential of our staff’s creativity.”

The Shipyard was built for internal use by the agency, and the more than one hundred topics discussed there in a year are all related to the agency’s long-term vision. Over four thousand officers used the center last year, and inspector teams for substantial tax evasions are frequent users, as De Lange suggests. The Shipyard consists of more than a dozen different kinds of rooms for different types of discussions and activities. In addition to The Brain and The Silence, spaces include “The Workshop” for prototyping ideas, “The Harvest” for refining rough ideas, and “The Theater” for developing participants’ perspectives and mind-sets. They are all well designed to meet their specific objectives.

Physical space is not everything at The Shipyard, however. Choosing the right topic and designing appropriate processes are keys for success. De Lange and his team are in charge of selecting topics—what will and will not be discussed at The Shipyard—and designing discussion processes: whether there will be just one workshop or a sequence of multiple workshops, who will be invited, which room(s) to use, what methodologies of discussion to use, what type of facilitators to assign. A leading concept of The Shipyard is “license to disturb.” Through creative ways of generating, prototyping, and executing ideas of officers, the agency has gained significant economic benefits, including generating more efficient methods of tax collection.

The Shipyard is one example of Future Centers spreading across Europe. A couple of dozen Future Centers have been launched by government agencies, public-sector organizations, and private companies. The centers are basically highly participative working and thinking environments for accelerating innovations via co-creating, prototyping, and building breakthroughs. Although their purposes vary depending on organizations’ aims and context, there are common assumptions behind them. All the organizations face issues so complex that they need more creative ways to solve them through the fusion and creation of knowledge by diverse stakeholders.

Choosing the right topic and designing appropriate processes are keys for success.

The World’s First Future Center

The first Future Center was built at Skandia Life Insurance in Sweden in 1996. Skandia was already well known as the first company to successfully implement intellectual-capital management. After their efforts to leverage intellectual capital, the company realized they needed special environments with spaces, methodologies, and tools that could maximize the value of those invisible assets. Dr. Leif Edvinsson, one of the key drivers of intellectual-capital management at Skandia, and his team believed the headquarters building or branch offices were not the best places to generate and test wild new ideas for the future. After team discussions and some experiments, the company created the first Future Center by renovating an old lakeside house. A number of teams visited it to think in new ways. They developed many ideas, some of which have resulted in major successes over time.

The Spread of Future Centers

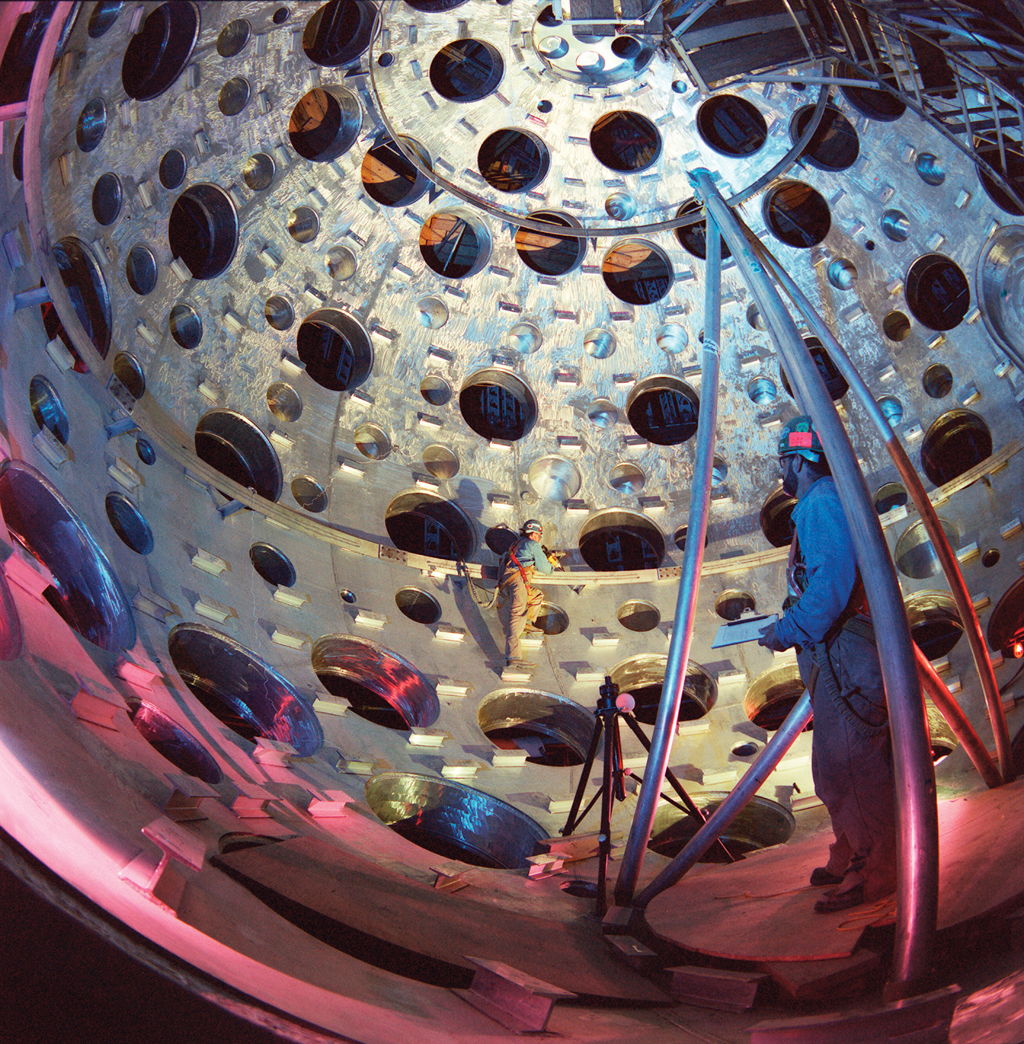

Ceiling of The Silence at the Dutch Tax and Customs Administration’s Shipyard. Photo courtesy of Naoki Ogiwara

Similar thinking in the United Kingdom led institutions including Royal Mail and the Department of Trade and Industry to open their own centers around the year 2000. Inspired by the success of Skandia’s pioneering Future Center, other organizations in Europe began their own initiatives. There are currently more than twenty European Future Centers in both public and private sectors. “Dialogues House” is a Future Center owned and operated by ABN AMRO, one of the largest banks in Europe. It was launched in 2008 by drastically renovating a trading room. Like The Shipyard, Dialogues House has specialized spaces, including “Sky Box,” semi-opened mezzanine space for collaboration; “Pressure Cooker,” closed space for brainstorming and intensive discussions; and “Forum,” for large-scale events with studio features. The bank’s purpose in building Dialogues House is to drive innovation by incubating ideas related to entrepreneurship, innovation, sustainability, and collaboration. It is also open to outsider social entrepreneurs and nonprofit organizations. Many business ideas have been turned into actual businesses, including, for instance, using the bank’s credit management abilities in new areas such as the art trade.

The movement landed in Japan in 2007. KDI (Knowledge Dynamics Initiative), a small consulting unit of Fuji Xerox, launched its Future Center in Tokyo. It is used mainly for holding workshops with Fuji Xerox clients, many of whom visit the center every day. Over 3,500 people visited the Future Center in 2010. KDI has formed a “Future Center Community” with more than forty Japanese organizations to expand the movement in the country. Some other Japanese organizations have launched their own Future Centers.

Key Elements of a Future Center

Although each Future Center has its own unique features, they have some things in common. All centers are facilitated working and meeting environments that help organizations prepare for the future in a proactive, collaborative, and systematic way. To realize the objectives of creating and applying knowledge, developing practical innovations, bringing citizens in closer contact with government, and connecting end users with industry, they share some key elements:

- Careful design and use of space. Extraordinary settings encourage creative mind-sets and behavior; different modes of discussion require different spaces.

- Facilitation. A skilled facilitator is needed to energize and encourage participants and support the processes.

- Process design. The staff need to be familiar with various styles and methodologies associated with workshops, discussions, and dialogue and be able to choose the appropriate one in a given situation.

- Hospitality and playfulness. Participants are only able to extend their limits when they feel safe and have fun.

There’s no magic behind the success of Future Centers; they simply follow the rules of individual and organizational creativity. The key is a holistic approach to bring out that creativity by tapping the power of space, dialogue, and process. Increasing numbers of European and Japanese organizations have started to see the benefits of the creativity inspired by these idea incubators. And the concept is still evolving: the Future Centers of the future will likely be even more effective.

About the Author

|

As a senior consultant at KDI, Fuji Xerox, Naoki Ogiwara has led several dozen client projects on knowledge management, change management, and Future Centers as well as global benchmarking research for more than a decade. |