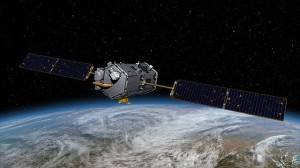

NASA's Orbiting Carbon Observatory is on the launch pad at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Image credit: NASA/Randy Beaudoin

May 10, 2011 Vol. 4, Issue 3

OCO-2 demonstrates that there is a way to bounce back from failure and forge ahead with the mission.

On Tuesday, February 24, 2009, the Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO) launched into the sky aboard a Taurus XL rocket. Its mission was to measure carbon dioxide in the atmosphere globally. Ultimately it would provide a better understanding of Earth’s carbon dioxide emitters and sinks. But the mission did not go according to plan when OCO left the ground.

“It was there one moment and then gone the next,” said Ralph Basilio, then OCO deputy project manager. “We didn’t have anything.” OCO had missed its insertion orbit due to a mishap with a faulty launch vehicle payload fairing. The hardware that didn’t burn up in the atmosphere splashed down in the Pacific Ocean near Antarctica. The next day, the OCO team returned to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “By the end of the day Friday [three days after launch], we had put together initial study results [for a replacement mission] and sent it off to NASA Headquarters,” said Basilio.

There was no time to grieve. The OCO team shook it off and got to work. “We went from emotional shock to we need to roll up our sleeves and get the work done,” said Basilio. The mission was that important.

Sleeves Up

In the six months that followed, the OCO team needed to formally establish the “why” and “how” of and Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) mission. Basilio, now the project manager of the proposed OCO-2 mission, and his team took a step back. An OCO science team established the “why”: the scientific community simply cannot wait for a future mission. OCO’s measurements were fundamental to future missions laid out in the NASA’s Earth Science Decadal Survey designed to inform global climate change science and policy.

A team of engineers worked the “how.” Options included: a direct rebuild of the original OCO; rebuild and improve on OCO; co-manifest an OCO-like instrument on another planned mission; put an OCO instrument on the International Space Station; or rebuild and co-manifest an OCO observatory on a shared launch vehicle. The team decided that a direct rebuild with necessary improvements was the best option given the mission risk profile and tight schedule.

In September 2009, NASA presented an almost “carbon copy” OCO-2 mission plan to the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). By early 2010, the OCO-2 team received Authority to Proceed (ATP). NASA assigned project management to JPL. Orbital Sciences Corporation was selected to rebuild the spacecraft and provide the Taurus-XL launch vehicle. OCO-2 has a 28-month development cycle from the ATP received at Key Decision Point C (KDP-C) to launch.

Challenges

One of the most daunting challenges for the OCO-2 team is the compressed schedule. OCO’s original project lifecycle was 36 months long. OCO-2 has 28 months. Currently in Phase C, the team is building, assembling, and testing hardware. Getting to this point hasn’t been easy.

OCO-2 went through a tailored formulation phase. Since OCO-2 is a near-replica of OCO, the project team was permitted to skip key decision points (KDP) A and B, and several other technical reviews. As a result, the formulation phase was only eight months long, rather than a more typical 21 months. They completed their Critical Design Review (CDR) in a single day in August 2010. “People said it couldn’t be done,” said Basilio. The OCO-2 team walked away with two action items, both of which were closed out on the second day during a splinter session. KDP-C followed a month later. Basilio, who worked on missions like Mars Pathfinder and Deep-Space 1, said that “a lot of those ‘faster, better, cheaper’ experiences that I had back then are helping me on OCO-2.”

Schedule aside, the OCO-2 team also has had to face the reality of parts obsolescence. The original OCO design incorporated a few now obsolete instrument components, including a memory chip on the RAD6000 flight computer. The team also has had to account for long-lead parts, redesign certain components, or find certain components elsewhere. In the case of OCO’s instrument cryocooler assembly, there wasn’t a spare, and the team worked with the GOES-R project to acquire one.

Heading into the summer, Basilio has identified one critical path item: an optical bench assembly. Described as “the heart of the instrument,” the team has instituted corrective actions to catch the team back up over the next few weeks. Time remains the big driver. “We need to make sure that the product is correct and that we work only as quickly as proper caution permits,” said Basilio. “Our big challenge is to make sure that we get to the launch site as scheduled.”

OCO-2 is scheduled to launch in 2013, though the recent mishap with Glory, which bears similarities to the original OCO mission, has introduced new uncertainties.

On Learning

With a second chance to fly, the OCO-2 team is has a unique opportunity. “Instead of documenting lessons learned for potential incorporation into a future endeavor,” said Basilio, “we have this opportunity to actually go ahead and employ those lessons learned.” Ultimately, the OCO-2 team hopes to be able to measures how successful these lessons were to the success of the OCO-2 mission.

OCO-2’s lessons are already making their way elsewhere. The Jason-3 project team sits four floors below the OCO-2 project team at JPL. “We have an opportunity to talk to each other once in a while,” said Basilio, who also worked with the mission’s project manager on Jason-2. “I try to provide him [the Jason-3 project manager] with as much information as I can to help him along.” Basilio believes that this type of knowledge sharing is beneficial not only to the OCO-2 project, JPL, and NASA, but also to the American taxpayer in the long run.

This is an artist’s concept of the Orbiting Carbon Observatory. The mission, scheduled to launch in early 2009, will be the first spacecraft dedicated to studying atmospheric carbon dioxide, the principal human-produced driver of climate change. It will provide the first global picture of the human and natural sources of carbon dioxide and the places where this important greenhouse gas is stored. Such information will improve global carbon cycle models as well as forecasts of atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and of how our climate may change in the future. Image credit: NASA/JPL

The lessons and knowledge gained from OCO-2 will also be employed for a possible OCO-3 mission of opportunity and inform the Active Sensing of CO2 Emissions over Nights, Days, and Seasons (ASCENDS) mission. ASCENDS is a movement away from OCO’s passive measurement system to an active measurement system. OCO’s instrument looks at the spectra of reflected sunlight, ASCENDS is envisioned as an active laser system. “You can actually look at the carbon dioxide on the dark side [of Earth],” explained Basilio.

OCO, OCO-2, and the OCO-3 mission of opportunity are the evolutionary steps needed to get to ASCENDS. “We’re hoping to use the experience that we’ve gained using a passive system to help us figure out how to enact an active laser system that will provide more precision, more accuracy in the future.”

On People

After the failure of the first OCO mission, “coming to work every day was a little bit of a struggle, at least for me personally, because of the unknown,” said Basilio. “A lot of us just couldn’t wait until NASA Headquarters made the official decision to say ‘OK, you guys are real, hit the ground running. Here are the resources that you need and make it happen. If you need any help, we’re here to facilitate.’”

“One of the key strengths that we have is that we have a very, very good team,” he added. “Not just here at JPL, not just internal to the project and with our industry partner, but the program office and NASA Headquarters.” Managing relationships with all of the project stakeholders has been vital to OCO-2’s promising progress.

“We lost OCO because of something we couldn’t control,” said Basilio. Now, taking on OCO-2 and its compressed schedule, Basilio said the stress is worth it. “For me, getting ready for launch and getting ready for mission operations has always been a high point.” Basilio and his team take pride in giving the nation’s decision-makers and public the information that they need so they can make informed decisions. “How could you want to avoid something like that?”

“We don’t just come to work and punch a clock and walk away from it. If you really look at the folks at NASA, people are really dedicated to doing a good job – not just for the sake of the job, but because they believe in that endeavor.” Basilio is proud to lead his 100-plus member team. “People are the critical component in any endeavor that we have at NASA,” he said. “People are willing to work together for a common cause and that’s really the thing that’s going to carry us through.”

Read a 2010 interview with Patrick Guske, OCO-2 Mission Operations Systems Engineer, about the lessons learned efforts taking place on OCO-2.

Read the OCO Mishap Investigation Results.

Read the news release about the Glory Mishap Investigation Board.

NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory is on the launch pad at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

Featured Photo Credit: NASA/Randy Beaudoin