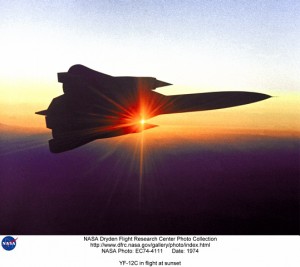

This month marks 34 years since the close of NASA’s YF-12 Blackbird research program, which yielded a wealth of knowledge about supersonic flight.

The so-called YF-12C in flight at sunset. The YF-12C was the second production SR-71A (61-7951), modified with YF-12A inlets and engines, and given a bogus tail number (06937). It replaced a YF-12A (60-6936) that crashed during a joint USAF-NASA research program.

Photo Credit: NASA

On March 5, 1970, Fitzhugh Fulton piloted the first YF-12 Blackbird as part of NASA’s joint research program with the U.S. Air Force. The YF-12 was one of the Blackbird family, which included the A-12 and SR-71 aircraft. Over the course of the program’s ten years, the NASA’s YF-12 flights provided valuable data on supersonic flight. In recognition of the YF-12’s contributions, ASK the Academy spoke with Dryden Flight Research Center’s Peter Merlin, author of Mach 3+: NASA/USAF YF-12 Flight Research 1969-1979 (NASA SP-2001-4525), about the history of the program. Merlin has been involved in aeronautics history work at Dryden since 1997.

ASK the Academy (ATA): NASA’s YF-12 research program started shortly after the last flight of the X-15 program, which also studied supersonic flight. What made the YF-12 flights unique compared to the X-15?

Peter Merlin: Both the X-15 and YF-12 could be used to perform research at high speeds and altitudes. The primary difference was that X-15 flights were of extremely short duration, particularly the speed and altitude portions. The YF-12, on the other hand, could cruise at high speeds and altitudes for extended periods of time. This was a huge advantage to researchers because more data could be collected.

ATA: In order to get the program off the ground, NASA needed buy-in from several reluctant partners, primarily the U.S. Air Force and Lockheed, in order to acquire the YF-12 (and later a SR-71) planes. What were some of the concerns that had to be overcome?

Merlin: Lockheed officials were initially reluctant to let NASA acquire a SR-71, or even to install instrumentation in one of the test aircraft, largely due to concern that NASA would then publish sensitive data. This was not an unreasonable concern since NASA is a research organization that typically makes the results of its studies known so that they can be used by industry to improve aeronautical technologies.

Initially, Kelly Johnson, the Lockheed engineer who led the design and development of the Blackbird program, saw much of NASA’s work with the Blackbirds as redundant since Lockheed had already acquired much of the same data through its earlier test programs. The Air Force still wanted to do some testing with the planes and saw significant cost-sharing opportunities in a joint program with NASA. Even Johnson eventually agreed that there might be benefits to working with NASA.

Eventually, the Air Force agreed that NASA could have two of the YF-12A interceptor prototypes as part of a joint research program. The YF12 didn’t have the stealthy qualities of the other Blackbirds in that it lacked the anti-radar treatments (radar absorbent structures) of the A-12 and SR-71 variants of the Blackbird family, which made it a little less sensitive. Later, a third airplane—an SR-71A—was added to NASA’s program, under the bogus “YF-12C” designation.

Once the Air Force and Lockheed were onboard, the collaboration became quite successful.

ATA: You wrote that Lockheed designers were hesitant to incorporate, and consequently didn’t include, Digital Fly-By-Wire flight controls in the Blackbird fleet due to potentially unknown problems. Later, NASA researchers did integrate another type of digital control called Digital Electronic Engine Control (DEEC) into the YF-12C Blackbird. While one system pertains to flight control and the other engine control, can you speak to why this decision was made?

Merlin: For Kelly Johnson, the simplest approach was usually the best approach. In manufacturing the Blackbirds, he rejected stainless steel honeycomb sandwich construction in favor of titanium structures that were easier to assemble. He chose conventional control system architecture over complex, and still experimental, fly-by-wire systems. These were good engineering decisions based on the state-of-the-art at the time.

Much of NASA’s YF-12 research involved propulsion systems. Perhaps the most important contribution was development of the airplane’s Air Inlet Control System (AICS). The Blackbird’s inlets were notoriously susceptible to a phenomenon called “unstart,” a violent interruption of airflow through the inlet ducts to the engines. The AICS virtually eliminated this problem.

ATA: You note several lessons that were learned from this research program. In your opinion, what would you consider to be some of the most significant lessons from the program?

Merlin: Generally speaking, the two most significant results of the NASA YF-12 research program were the development of more accurate analytical modeling techniques for supersonic aircraft design, and the legacy of structural, aerodynamics, propulsion, heating, and atmospheric physics data that that are likely to serve as the basis for developing future high-speed aircraft.

ATA: So this program produced data that is still relevant to today’s projects?

Merlin: Absolutely. That was one of the reasons why we established the Dryden Historical Reference Collection. It was made to be available to researchers, both external and internal, project management, project engineers, and technicians, so that they can learn the lessons of the past, figure out what was done right, what was done wrong, avoid repeating mistakes, and often times save a lot of money by not reinventing the wheel.

ATA: In your monograph you note that more than two decades passed after the program ended before a concerted effort to capture the knowledge of NASA’s YF-12 program was initiated. As you wrote the monograph, did you encounter any challenges in piecing together the story?

Merlin: There were only two relevant challenges I encountered with regard to capturing the program’s history after so much time had passed. First, I would like to point out that although NASA (and previously the NACA) has had an organizational presence at Edwards Air Force Base since 1946, the center did not establish the History Program until 1996. As a result, a vast amount of material had been lost, destroyed, or given away over the years. What remained was squirreled away in warehouses, supply closets, under stairwells, and occasionally in people’s offices. I’m not just talking about material related to the YF-12, but to all of Dryden’s programs. The effort to organize and catalog this material, and make it available to researchers, was a massive undertaking on the part of the Dryden History Office staff.

The second obstacle I ran into involved a truly heartbreaking story. While I was interviewing YF-12 project engineer Gene Matranga, he told me that he had kept a daily diary in which he meticulously recorded details of everything that went on during the program. This, of course, would be the best sort of primary source material—detailed notes written at the time of the events, not subject to the ravages of time or memory. When Gene left NASA for a job with Lockheed, he took the notebook with him. Since many of the technological details remained sensitive or classified, the notebook was locked in a vault. Sometime in the early 1980s, all classified material in Lockheed’s possession had to be properly marked and stored. It was often easier to destroy unneeded material rather than go to the effort of bringing it into compliance. Unfortunately, Gene’s notebook went through the shredder, and a one-of-a-kind resource was lost forever.

ATA: That is heartbreaking. How has that story and others like it informed your view on the importance of preserving the history and knowledge of programs like this?

Merlin: We have a lot of stories like that. We have had a lot of people contact us from time to time. We get calls from people saying, “Hey, I’m retiring and I have a bunch of stuff that I was going to throw out, do you guys want it?” Of course we want it, because a lot of the time there is some great material there. We will make road trips to go and look at this stuff and bring it back and boy we’ve gotten some great stuff that way. Now, there’s a lot of junk, too, which we don’t need, but it’s better to look at it rather than find out some really valuable content was thrown in the dumpster.

View images from Dryden’s YF-12 program.

Read through commonly asked questions about the Blackbird Program. (PDF)

Learn more about the Dryden History Office.