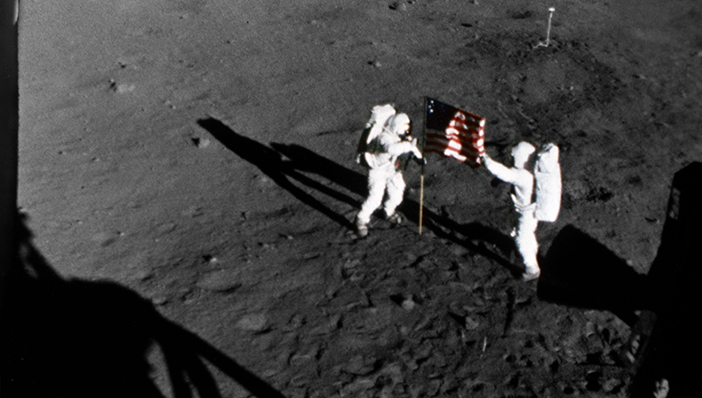

An interior view of the Apollo 13 Lunar Module and the "mailbox." The "mailbox" was a jerry-rigged arrangement which the Apollo 13 astronauts built to use the Command Module lithium hydroxide canisters to purge carbon dioxide from the Lunar Module. Lithium hydroxide is used to scrub CO2 from the spacecraft atmosphere. Since there was a limited amount of lithium hydroxide in the Lunar Module, this arrangement was rigged up using the canisters from the Command Module. The "mailbox" was designed and tested on the ground at the Manned Spacecraft Center before it was suggested to the problem-plagued Apollo 13 crewmen. Because of the explosion of an oxygen tank in the Service Module, the three astronauts had to use the Lunar Module as a "lifeboat."

Photp Credit: NASA

There are actually several Tom and Jerry cartoons in which Jerry (the mouse) rescues a goldfish from Tom (the cat). Inevitably, in one of these episodes, a fish bowl filled with water descends upon Tom’s head only to encase it.

Just punishment, a five year old might think, for trying to eat a poor little fish. And, to a five-year-old brain, an equally amusing incident.

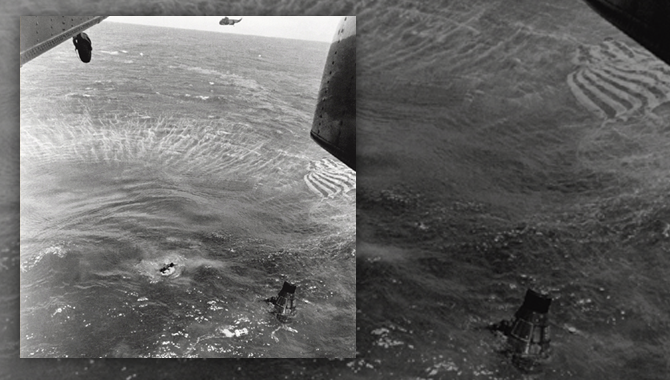

In July of last year, two astronauts successfully and safely completed a spacewalk only to discover upon entering the International Space Station (ISS) that water had gathered inside of one of their helmets. The ISS team concluded that the water had leaked from the drink bag inside of the spacesuit, which was inadvertently squeezed.

Soon unwelcomed water was discovered once again, but this time while on a spacewalk. The astronaut continued the spacewalk until the vexing liquid had reached his face, thus making it difficult to see and breathe. The astronaut returned to the ISS airlock safely and subsequently stated that he now knew what it feels like to be a goldfish.

We try to keep our sense of humor at NASA (estimates of how many of us were once five year olds are as high as 100%); however, “head in fishbowl” incidents are a cause for concern. Consequently, the Mishap Investigation Board identified several causes for these related incidents, with two of the causes including 1) inorganic material blocking the holes in the suit venting system and 2) the initial misdiagnosis of where the water had come from upon its first appearance. Needless to say, the second appearance of water could have drowned the astronaut floating in the emptiness of space.

To practitioners and advocates of Knowledge Services, the incidents could be a lecture on the normalization of deviance: though it was not normal for water to appear inside a space helmet, the misdiagnosis made it seem less aberrant. And the second occurrence of water was—in a sense—shrugged off when it reappeared. Only when the water rose to a threatening level was the spacewalk cut short.

There is something child-like in our natural reaction to situations where we either think a problem will go away—that it is just a fluke—or even our counterpart natural reaction that we can fix something before anyone really notices. To this second reaction—fix it before anyone catches you or, worse, blames you for breaking it—much comedy arises. How many times do we watch, like a voyeur, a character finding something broken or actually breaking something and then hiding it or fixing it before someone sees?

NASA has both a famous and unsettling history of fixing things just in the nick of time. While there are many notable quotes from Apollo 13 (and one you might never want to hear again), one popular line follows when a filter needs to be repurposed but its shape makes that complicated. Literally, a square peg needs to fit in a round hole or the crew of Apollo 13 will die. The quote is the problem statement: “We gotta find a way to make this (square filter) fit into the hole for this (round filter) using nothing but that (a mess of loose materials found on Apollo 13).” The engineers then worked as a team to share technical expertise to fix the problem.

Organizational Psychology and Knowledge Management are so intertwined that some academic institutions, such George Mason University, have combined both into a single Masters degree. Graduate students studying Psychology should be familiar with the concept Functional Fixedness: the bias of seeing or using an object in the manner in which it is traditionally used. The heroes on the ground in Apollo 13 take objects—including a sock—and repurpose them to make them function in a manner for which these objects were not designed. They are fixing a problem by not being fixated on what the original objects were created to do. The eponymous “MacGyver” TV Show has now entered our language as a verb for taking contrary objects and miraculous making something new. Knowledge of how it functions was paramount; what it was intended for became immaterial.

With Knowledge Services, it is the best knowledge practitioner who can take captured knowledge and apply it in the most original way. This is innovation twice over. Over the last fifty years, psychological tests have shown that the average five-year-old tends to be less functionally fixed than older children or adults (who are not engineers). However, when five-year-olds break something or “just found it that way” and don’t want to be in trouble, they are the best at jerry-rigging it to appear not broken.

So… thinking like a five-year-old is good… but only up to a point. We must capture and share knowledge and then apply and repurpose it in creative ways. And when we discover something is broken, or we break it ourselves, we should work as a team—and not like a solitary child fearing punishment, or hoping it will go away, or that no one will notice—until we find the root causes and the best solution to making it work.