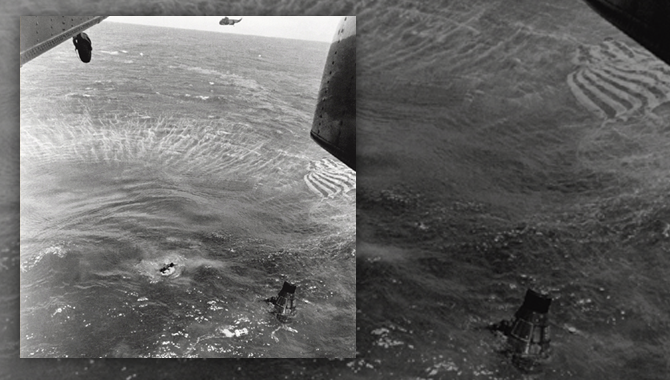

A U.S. Navy frogman, deployed from the hovering helicopter, swims next to the spacecraft and makes contact with Astronaut L. Gordon Cooper inside, as his fellow team members bring up the floatation gear to be attached to the spacecraft. The main chute floats at top left, and the ejected reserve chute floats at the lower right of the spacecraft in the green dye area.

Photo Credit: NASA

The latest hit song by the Counting Crows (after a six-year gap) now rides the airway, and in one line of its Beatlesque word associating imagery, Adam Duritz jubilantly sings a verse, launching with a bracing “Spaceman!” and ending with a crooning “Geronimo!”

According to The Straight Dope, shouting “Geronimo!”—before jumping off or out of something relatively safe into something relatively not safe—all originated with Private Aubrey Eberhardt, a WWII parachute tester in the U.S. Army. Gerard M. Devlin, who wrote the 1979 book Paratrooper, has gone on the record with direct quotes linking the Apache warrior’s name:

“All right, dammit!” shouted Eberhard, “I tell you jokers what I’m gonna do! To prove to you that I’m not scared out of my wits when I jump, I’m gonna yell `Geronimo’ loud as hell when I go out that door tomorrow!”

Private Eberhardt may have indeed seen the 1939 movie Geronimo the night before a mass jump of chutists leaping in close succession. And as he walked home with his friends after seeing this movie, he may have indeed been teased about the next day’s jump. There is also speculation that “Geronimo” was shouted to time the deployment of a test parachute; in case it does not deploy, a reserve chute is pulled with the long vowel. Conflicting origination stories fly.

At NASA, all 31 days of October tick off the Conflict Resolution Month Initiative, and at its center, Thursday, October 16, NASA has declared Conflict Resolution Day. The month began with a message from Administrator Charlie Bolden who stated that the agency’s “participation in this Conflict Resolution Month Initiative will help to strengthen the agency’s commitment to fostering an environment where employees feel they can communicate concerns and dissenting opinions without fear of reprisal.”

Knowledge Management and Conflict Management may not share a huge swath in all Venn diagrams, but there can be some overlap— a crucial place where NASA is shining a light. One term from cultural “norm” that NASA knowledge services practitioners warn against does impede mission success—and to which Administrator Bolden could be alluding to in the above paraphrase—is “Organizational Silence.” This entrenched silence occurs when employees do not feel they can communicate their concerns or dissenting opinions, perhaps because they fear reprisals, or fear they will be ignored, or feel that their opinions won’t matter anyway. Silence does not necessarily equal disaster in even the most critical situations when a valuable point of view is not shared. However, and unfortunately, there is that vulnerability that disaster will strike. One famous case study is The Tenerife Incident in which two planes collided on a foggy runway (before the advent of radar). Organizational silence was a contributing cause of the accident that claimed 583 people. If a dissenting opinion—captured forever in a cockpit transcript—had been more rigorous stated, it might have convinced the captain—who was in a rush—not take off and avert the accident.

Due to the unlikelihood of deadly events, as well as a general nebulousness of the piling up of root causes, most of us do not blame mishaps squarely on the slouched shoulders of Organizational Silence. This silence is always one of several root causes. Further, the “availability heuristic” illustrates the danger of why this lethal wallflower is not pulled alone into the floodlight. A 1973 article on “availability” bias, written by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, bears out that individuals actually reckon the frequency of something happening on how readily the cause is available for recall.

There is always the danger of failure: our silence can only aggravate that danger. Whether it is trying to write another hit pop song, or surviving a jump with an experimental chute, or nailing down where and when a curious exclamation comes from, the best thing to shout when we are hesitant to speak up just might be “Geronimo!”