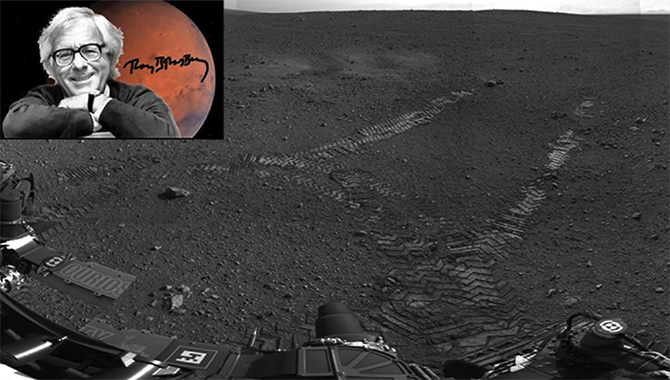

On August 22, 2012, the rover made its first move, going forward about 15 feet (4.5 meters), rotating 120 degrees and then reversing about 8 feet (2.5 meters), from its landing site. The landing site was subsequently named Bradbury Landing, named after Ray Bradbury, whose first book was The Martian Chronicles and who was born on August 22, 1920.

Photo Credits: NASA and AP

What lesson can be learned from real and fictional portals?

In the short story “The Veldt” (originally published in 1950 as “The World the Children Made”) by Ray Bradbury, the Hadley family lives in an entirely automated house, complete with a virtual reality room, which can create any world from occupants merely thinking about it. The room is creepily referred to as “the nursery” throughout the story, a place in which the Hadley children become obsessed. Soon, as the two Hadley kids put away childish things, their favorite brainwave-conjured setting for the room is a hot and dry grassland ruled by lions.

Distraught, Lydia Hadley confesses to her husband George: “I feel like I don’t belong here. The house is wife and mother now, and nursemaid. Can I compete with an African veldt? Can I give a bath and scrub the children as efficiently or quickly as the automatic scrub bath can? I cannot.” In 2015, in the age of the demographical preschoolers having an utter meltdown when the iPad battery needs charging (or worse, having a screen taken away as punishment), we can see where this story is going.

One theme that a seasoned knowledge practitioner hears over and over again is that technology is not the panacea (Panacea is the Greek Goddess of Universal Remedy) for all of our knowledge sharing challenges. If you build, say, an online portal for sharing lessons learned, it does not mean “they will come,” as world-renowned dead baseball players did when Kevin Costner built a baseball diamond in Field of Dreams. There are real life issues of taking the time to write new content, of confidentiality and transparency, of the limitations in “findability” in searching, and of potential users not knowing (or remembering) that the resource is there. Or could it be that an online portal for work does not hold the same appeal as a virtual reality room in the comfort of your own home?

With any portal for sharing knowledge, there is also the mindset of not wanting to admit (input) making a mistake or asking (output) for help from a network because that’s admitting we don’t know everything. Lastly, potential users of a new technological fix may not want to be users since they were not consulted as interface designers of the new solution.

Regardless, living in the onslaught of technology and Big Data, we may not have become obsessed with all new bright and shiny things, but we are overly reliant on the digital tools we think we have mastered. We see email as a way to archive. It turns out, as Jennifer Stevens, Chief Knowledge Integrator, Marshall Space Flight Center, pointed out in a recent Masters with Masters interview, that there are serious problems in expecting our knowledge to be captured in our emails. We still need to take some time to write down our lessons learned, best practices, and case studies. We still need to take some time to perform research to find lessons learned, best practices, and case studies and apply all of the above during all stages of life cycles of our project and programs.

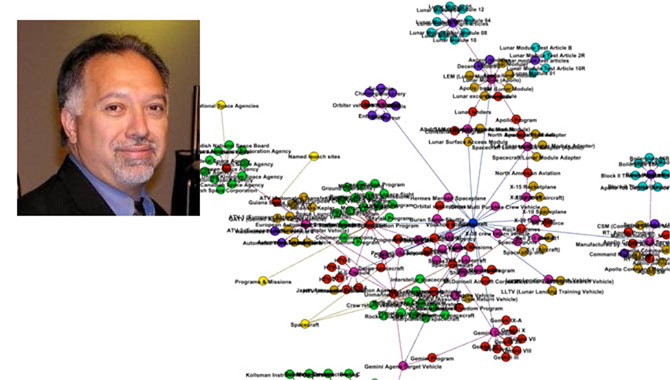

In this age of screens, nothing is perhaps more important than face-to-face interaction. If we joke that “video is the new document” to those before or behind a lens, we can take this joke one hearty laugh further and say that actually talking to someone live and in person is the new video. One of the six categories on NASA’s Knowledge Map is Face-to-Face Knowledge Services. These activities are defined as any event that brings people together in person to share knowledge (e.g., forums, workshops, Lunch and Learn, Pause and Learn, etc.). The reach of these experiences can be multiplied through online tools such as videos and virtual dialogues, but they begin with the real breath of live experience.

As NASA’s workforce prepares for retirement in droves, capturing the “tacit” knowledge in the living repository of gray matter between peoples’ ears becomes more and more important. While there are several viable solutions for capturing this knowledge including those means mentioned above, there is nothing as imaginably rewarding as mentoring. While phone calls and email threads are helpful, what was called the “power lunch” in the last millennium remains just that. Break bread and build bridges. No one walks away from the table with less than they had when they arrived at the table. Knowledge does not diminish the more that it is shared. The more people have knowledge, the more valuable it becomes, and one hopes, increases in perpetuity.

Ray Bradbury, born August 22 in 1920, wrote in 1985 for PC Magazine: “I see nothing but good coming from computers… In a sense (computers) are simply books.” Twenty-five years later, two years before his death on June 5, 2012, he told the BBC News, “We have too many cellphones… We have too many machines now.” Of course, the author of The Martian Chronicles offered a balancing quote: “Machines on their own don’t go awry, people do.” This is one of the messages of “The Veldt”—as the virtual reality room drones on, as inputted by the children who have gone awry, as two hidden lions crouch devouring something lost in the tall grass, parents dead out of sight…

“Garbage in, garbage out” crops up in our texts as GIGO. So does F2F. Perhaps one day “KIKO” will be equally recognizable as meaning best learning coming from a live knowledge transfer.