NASA pilot Dave Wright reviews pre-flight checklist prior to take-off.

Photo Credit: NASA

So far, my life and career have weathered many mistakes.

But the best (that is, most survivable) lessons learned come from serious mistakes made by others. Politicians and physicists may agree. Otto von Bismarck once remarked, “Fools say that they learn by experience, I prefer to profit by others’ experience.” Werner Karl Heisenberg narrowed it down even further: “An expert is someone who knows some of the worst mistakes that can be made in his subject, and how to avoid them.”

Here is one of my best mistakes.

The year is 2004 and I’m at an altitude of 8000 feet in Banning Pass, ten miles north of Palm Springs Airport, with two passengers in my Cessna Cardinal. I’m reading my Descent for Landing checklist, as I’m about to radio the airport tower for landing clearance. Suddenly, dense black smoke begins to fill the cockpit. I flip the checklist over and follow the five steps listed on the back under In-Flight Electrical Fire:

(1) Master Switch to Off

(2) Other Switches (Except Ignition) to Off

(3) Close Vents/Cabin Air

(4) Extinguish Fire (in this case, I isolated a faulty transponder)

(5) Ventilate Cabin

These steps took maybe 90 seconds. Then we descended to an uneventful landing. The crisis hardly caused a significant increase in heart rate, because I just followed the checklist.

The formal checklist derives from a lesson that was learned on October 30, 1935, during a test flight of the B17 bomber prototype. The pilots attempted to take off with the tail wheel locked; this prevented the wheel from swiveling and resulted in a crash and the death of both pilots. From then on, Boeing provided a printed checklist with each production version B17. (Previously, pilots were expected to make their own checklists.) Today, all airplane manufacturers provide a pilot’s handbook containing checklists specific to the model of plane. Most contributions to the content of airplane checklists come at the cost of someone’s life. In Law Abiding Citizen, a 2009 film, we hear, “Lessons not learned in blood are soon forgotten.”

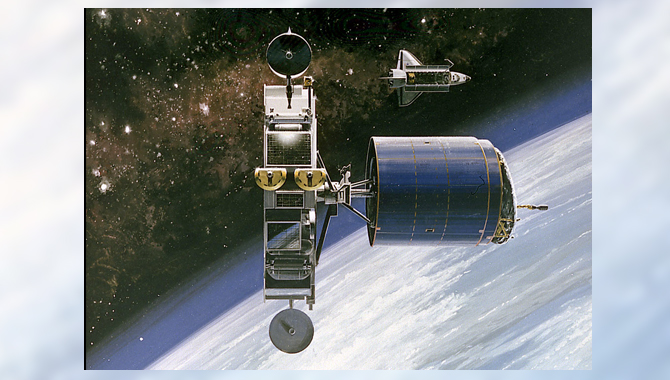

The development and operation of spaceflight missions also involve complex procedures in which an error—such as missing one step in a procedure—can be catastrophic. Hence, we use checklists in everything from procedures in system test plans to reminders on how to restore backups to our computer. With so many risks that are “unknown unknowns” in NASA programs and projects, checklists assure adherence to routine practice and help limit risk to the more novel elements of a mission.

Why do I love checklists? Because in 2004 a checklist helped avert what could have been some serious unpleasantness. And because rather than letting my imagination run amok to my detriment (otherwise known as “panicking”), effective use of checklists allow me to direct my imagination to more productive purposes.

David Oberhettinger is the Chief Knowledge Officer of the Jet Propulson Laboratory.

Read more articles in the “My Best Mistake”series.