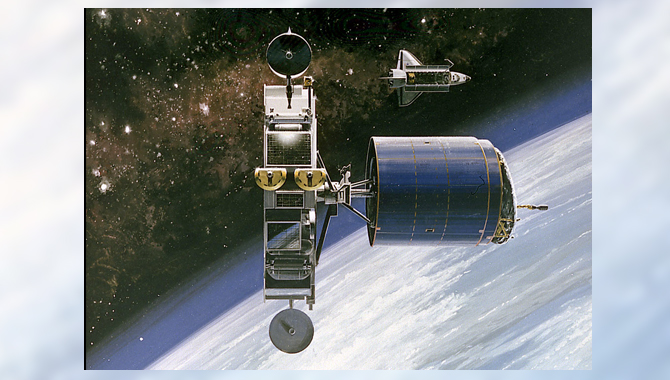

The GALEX spacecraft before its launch in 2003.

Photo Credit: NASA/JPL

I was project manager for GALEX, the Galaxy Evolution Explorer.

This mission was ultimately a success, but—like any mission—it had its share of problems along the way. Some of them were cliffhangers that took a good bit of ingenuity and determination to solve.

One mistake we made along the way taught me a valuable lesson. Our low-cost mission had a small, hard-working team that included a university group designing the photon-counting detector assemblies at the heart of our instrument. There was no question that for this type of detector this team was the best in the business. But the detector readout electronics were being designed and prototyped by a single design engineer who was overwhelmed by the challenge of simultaneously delivering electronics for our project and for an instrument headed for the Hubble Space Telescope. The mistake I made was not to bring in help as soon as it became clear that help was needed. Instead, I yielded to the detector team’s argument that bringing in new help would further burden their engineer and slow him down. They sought to isolate him so he could work on the unit without distractions. I didn’t parachute in reinforcements until it was too late.

Shortly before the flight electronics were due to be delivered, the engineer suddenly resigned and left the university. When we looked at the state of the instrument he had been building, we discovered that an important portion of the readout electronics didn’t work and contained serious design flaws. It took a crash program working with another electronics supplier to develop a replacement element.

The lesson learned is to throw a drowning man a life ring, even if he doesn’t want one.

And he will almost certainly say he doesn’t want or need help when you offer it. Time and again, project leaders are faced with a schedule-driven situation where some group or individual is clearly overloaded trying to make their delivery date and could use some outside help. Adding an outsider to the effort is nearly always resisted. For one thing, ego comes into play. Engineers don’t like to admit that they can’t solve all the technical problems themselves. Also, your already over-burdened team members are likely to tell you they don’t have time to bring a new person up to speed, that adding personnel will result in further delay and expense. Their resistance should be resisted. The right answer is nearly always to bite the bullet and bring in the additional help. I experienced this in a major way on GALEX.

They say that military defeats can be summed up in two words: “too late.” That is a lesson that NASA project leaders should take to heart.

James Fanson’s twenty-eight-year career at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory has spanned technology development, instrument development, and flight project implementation. He was part of the team that repaired the Hubble Space Telescope; led the team that produced the preliminary design of the Spitzer Space Telescope; and, as project manager, led two telescope missions (GALEX and Kepler) to launch and early science operations.

Read more articles in the “My Best Mistake”series.