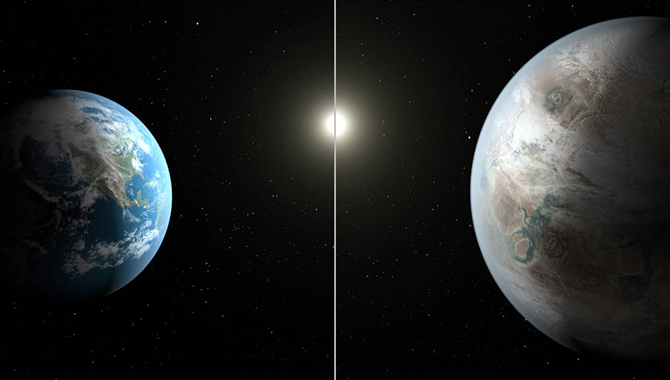

The HOPE team readied the RaD-X High Altitude Science Balloon in preparation for the launch at Fort Sumner, NM, on September 25, 2015. The project remained in flight for 24 hours as it collected data from two regions in the stratosphere.

Photo Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

On September 25, 2015, a novel mission provided new insight into cosmic ray energy in the upper atmosphere while advancing professional development at NASA.

The Radiation Dosimetry Experiment (RaD-X) was conceived as a means of supporting the safety and health of aircrew by measuring radiation that influences the exposure levels at aviation altitudes.

“Galactic cosmic rays are bombarding the atmosphere all the time,” said RaD-X principal investigator Chris Mertens. “The international commission on radiological protection classifies aircrew as radiation workers, yet they’re the only occupational group whose exposure cannot be quantified over their career. During solar storm events, radiation recommendations by the international community can be exceeded for [passengers], especially pregnant flyers, too.”

Before working on RaD-X, Mertens developed the Nowcast of Atmospheric Ionizing Radiation for Aviation Safety (NAIRAS) model. NAIRAS was positioned to provide critical data to help aircrew—as well as astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS), who are exposed to even higher levels of radiation—gain a better understanding of their health status and potential risks. NAIRAS would provide more reliable predictions of radiation exposure, which the aviation community could use to alter flights paths during solar storm events or modify the schedules of aircrew approaching radiation limits.

But NAIRAS could only be effective if the data it provided were reliable. To verify and validate the model, a team of 13 young engineers from Langley Research Center (LaRC) proposed the RaD-X mission. RaD-X was intended to obtain the first-ever high-altitude dosimetric measurements—at two different altitudes—of cosmic ray interaction in the upper atmosphere and to validate low-cost sensors that would work with NAIRAS.

RaD-X Project Manager Kevin Dougherty (left) and Frank Peri, Deputy Director of the Engineering Directorate at Langley Research Center (right), watch as Amber Agee-Dehart, Founder of the Cubes in Space program, applies a decal to the RaD-X cubesat. Photo Credit: NASA/Erin Bonilla

“RaD-X takes measurements high in the atmosphere, where the production of secondary particles occurs. These are the particles that actually provide the radiation exposure at aircraft altitudes, by colliding and breaking up and producing more particles. RaD-X was designed to characterize how well we’re predicting the primary particles coming in, which are the source of radiation exposure at aircraft altitudes,” said Mertens.

That wasn’t the only focus of the mission. “The second goal of RaD-X was to characterize low-cost, compact dosimeters that had the potential to be manufactured in large quantities and distributed globally on aircraft to downlink those measurements in real time and ingest them into the NAIRAS model to improve it in real time, in the same way that a meteorological weather forecast works,” he said.

The global science community concerned with space weather and aircrew radiation levels watched with interest as the RaD-X team moved forward. What few of them knew, however, was that RaD-X had a third objective: to advance NASA’s project management and systems engineering capabilities.

To achieve this aim, the project was fostered by a unique agency development program: Project HOPE [Hands-On Project Experience]. Sponsored by the Science Mission Directorate (SMD) and APPEL, Project HOPE gives early-career NASA engineers hands-on experience through the full life cycle of a suborbital flight project. A key goal of Project HOPE is to accelerate professional development by conveying essential skills and knowledge in a condensed timeframe, preparing team members to manage future agency flight projects.

Through Project HOPE, the RaD-X team designed, developed, built, tested, and launched the balloon. During the course of the project, each team member rapidly expanded their knowledge and abilities. APPEL helped build critical skills among the team members by providing fundamental courses such as Introduction to Aeronautics, Crucial Conversations, Spacecraft Systems Integration and Test, Requirements Development and Management, and a Langley-Influenced Skills Training course.

“The courses were helpful—especially because we did them very early in the process—to focus the team,” said RaD-X project manager Kevin Daugherty. “At the beginning of the project, a lot of the people on the team had not been exposed to [NASA Procedural Requirement (NPR)] 7120.5. Some of them probably couldn’t even have told you, when they started, that a project goes from phase A to F.”

He added, “From a training perspective, one of the biggest things that RaD-X afforded me was the ability to go through a project for the entire life cycle, from concept through flight.”

Denisse Aranda, the Integration and Test lead for RaD-X, agreed. “It’s been an amazing experience—we’ve taken RaD-X from concept to launch-ready in just 18 months.” She added, “I feel very grateful for this opportunity…It’s giving us the kind of experience it could take us a decade to get otherwise.”

Prior to RaD-X, Aranda was a test engineer responsible for conducting simulation tests. During RaD-X, her responsibilities were much broader: she worked with thermal, systems, and chief engineers to develop and understand the environment, then designed the entire test and worked with all the subsystem leads to ensure that the correct parameters were evaluated.

“That’s a really difficult thing to do,” she said. “Usually you don’t get that level of exposure variance until much later in your career.”

Working on the mission provided the team with hands-on training in all major phases of mission design and execution, complemented by mentoring and coaching in both formal and informal venues. The result was a customized, flexible, and integrated training approach that prepared the RaD-X team for mission success.

Amanda Cutright, RaD-X chief engineer, found the hands-on aspect of Project HOPE enormously beneficial. “I learn best by doing and seeing, and there is no better way than for me to try to execute using tools and techniques learned through a direct experience.”

Daugherty concurred, stating that the hands-on hardware experience was invaluable. “Getting to see how things fit together and what the challenges are. Discovering the small road blocks you never saw coming and the logistics that are harder to work through than you expected them to be.”

Despite their initial lack of experience, the RaD-X team put together a highly successful mission. On September 25, 2015, the RaD-X High Altitude Science Balloon launched from Fort Sumner, NM. It remained in flight for 24 hours, collecting data as it measured cosmic rays at two regions in the stratosphere. The first region was above 110,000 feet, at the edge of space. The second was between 70,000 and 89,000 feet, where the experiment remained overnight. That data was then fed into NAIRAS, with results that were better than anyone had hoped.

“We produced better science data than we expected,” said Daughtery. “We expected to be able to point Chris in the right direction—either to look up at the incoming levels or to look down at the complex physics—and then say, ‘Good luck looking at that area!’ But with the data we collected, Chris was actually able to identify the process that needs to be improved.”

“We wanted to provide the type of measurements that would tell us where we need to focus our attention: either on characterizing the primary particles or on the very complex region where the secondary particles occur,” said Mertens. “By looking at all of the measurements [that came out of RaD-X], we identified exactly the area on the NAIRAS model that needs to be addressed first. Unfortunately, that’s the complicated region. But it’s a very specific chain of processes: the creation of pions and their subsequent electromagnetic cascade particles. So we know exactly where we need to direct our attention into the NAIRAS model.”

The RaD-X experiment also identified a unique feature of a radiobiological quantity related to health risk.

“It turns out that quantity has a very different shape in the atmosphere, according to our measurements, than most models predict,” said Mertens. “It highlights the influence of cosmic ray primaries in the production of neutrons. It’s a very unique feature, a different feature that we were not anticipating but we certainly measured. Now we’re looking forward to how [these findings] will influence the community as people try to respond and improve their models. It’s really important to get that right in that region, because that is the source of the particles that result in exposure at aviation altitudes.”

Given the magnitude of the findings, a special upcoming issue of the peer-reviewed AGU journal Space Weather will be dedicated to RaD-X.

“When all the dust settles, after you smoke all the cigars and have the pizza parties and all of that after launch, it’s really the written record in the scientific journals that’s going to have the lasting influence in the science community. And having an entire issue in an international journal like Space Weather dedicated to RaD-X is a demonstration of what we accomplished,” said Mertens.

“I wouldn’t trade the experience for anything,” Daugherty concluded. “It was by far the best training experience I could have hoped for. We were ultimately quite successful. We came in at our scheduled launch day, we came in under budget—marginally, but still under—and we actually produced some great science results.”

With RaD-X completed, the SMD and APPEL are moving forward with a new Project HOPE Training Opportunity and looking forward to another successful launch, which is expected to take place in the summer of 2017.

Learn more about Project HOPE.

Watch a video of the launch of the RaD-X mission.