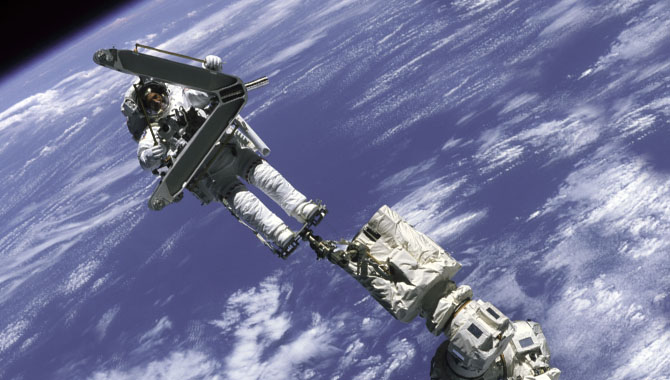

On October 26, 1977, as the space shuttle prototype Enterprise landed during the final ALT free-flight test, it bounced on the runway due to unexpected pilot-induced oscillation that resulted from a problem with the shuttle’s flight control computer.

Photo Credit: NASA

Forty years ago, the space shuttle prototype Enterprise set out to prove that the orbiter could return from space and glide to a precise, unpowered landing.

Between April 1981 and July 2011, NASA’s Space Shuttle Program flew five orbiters for a total of 135 missions. But the viability of the program was established based on the efforts of a different vehicle: the high-altitude glider Enterprise.

Constructed in less than a year, Enterprise was a full-scale orbiter prototype. Built to conduct in-atmosphere flight tests to validate shuttle systems and hardware, it lacked certain elements crucial to space missions, including a propulsion system, thermal protection, and reaction controls. In other respects, however, it provided a foundation for the design of the space shuttle Columbia and the orbiters that followed.

Structural assembly of the 150,000-pound Enterprise began in June 1974 and was finalized in March 1975. The vehicle was revealed to the public in 1976 before making its way to Dryden Flight Research Center (DFRC; now Armstrong Flight Research Center (AFRC)) at the end of January 1977 for the program’s Approach and Landing Tests (ALT). The nine-month ALT consisted of a series of ground and flight tests designed to evaluate Enterprise alone and in conjunction with the Shuttle Aircraft Carrier (SCA), a Boeing 747 retrofitted to ferry orbiters between NASA centers and launch sites when overland travel was not possible.

Enterprise was named after the spacecraft in the TV series Star Trek. When the shuttle prototype was unveiled to the public on September 17, 1976, attendees included members of the show’s cast. From left to right: NASA Administrator Dr. James D. Fletcher, DeForest Kelley (Dr. “Bones” McCoy), George Takei (Mr. Sulu), James Doohan (Chief Engineer Montgomery “Scotty” Scott), Nichelle Nichols (Lt. Uhura), Leonard Nimoy (Mr. Spock), Gene Roddenberry (series creator), U.S. Representative Don Fuqua (D-Fla), and Walter Koenig (Ensign Pavel Chekov).

Photo Credit: NASA

The primary focus of the ALT was to assess the aerodynamic flight control systems and subsonic handling characteristics of Enterprise in order to confirm its ability to fly safely in the atmosphere after reentry and then come to an unpowered, pilot-guided touchdown on a runway. The concept of a wingless body, such as the orbiter, landing safely and accurately without an air-breathing engine had been established by the joint NASA-Air Force Lifting Body Program, which ran from 1963 to 1975. The shuttle program wanted to utilize the same approach so that the orbiters could avoid the weight and cost of jet engines and their fuel. Additionally, without an in-atmosphere propulsion system, the shuttle’s payload capacity would be increased, enhancing the scientific value of its missions.

To prove the validity of this approach for the space shuttle, the ALT began with three taxi tests on the ground followed by five captive tests in which the unmanned Enterprise rode on top of the SCA for the duration of the flights. These tests verified the ability of the SCA to ferry the Enterprise and established the flight envelope for subsequent ALT tests.

Three captive-active flights followed. This time, although Enterprise remained attached to the SCA, its systems were activated and crew flew inside. Two two-person commander/pilot teams, who alternated flights, were assigned to Enterprise: Fred Haise/Gordon Fullerton and Joe Engle/Richard Truly. The SCA crew included pilots Fitzhugh Fulton and Thomas McMurtry as well as flight engineers Victor Horton, Thomas Guidry, William Young, and Vincent Alvarez.

The program culminated in five free flights designed to assess the handling of the shuttle at low speeds and during landing. For these, the 747 ferried Enterprise up to between 19,000 and 26,000 feet and released the orbiter, which then glided toward Earth before touching down at Edwards Air Force Base. Starting on August 12, 1997, the first three test flights were similar: an aerodynamic tail cone covered the orbiter’s three dummy main engines to reduce buffeting, and the crew landed on Rogers Dry Lake. The fourth flight added a variation: commander Engle and pilot Truly had to land the shuttle on the dry lakebed without the tail cone over the engines. This increased drag, which altered the handling characteristics of the vehicle. Nonetheless, the landing was a success.

The final flight in the ALT introduced a new goal: to establish that the orbiter could land precisely, at a predetermined mark, on a concrete runway rather than on a lakebed. Commander Haise and pilot Fullerton planned to bring the shuttle down on the 15,000-foot runway at Edwards Air Force Base. This would be the first flight for the team without the tail cone—and the first landing for the shuttle on concrete.

On October 26, 1977, the SCA ported Enterprise up to altitude for a final time and released her. Although Haise and Fullerton had prepared for the mission in NASA’s flight simulator, the vehicle performed differently than expected and the crew ended up coming in too fast. Haise hit the speed brakes, still aiming for the designated landing mark, but the shuttle overcorrected. It started to skip and bounce along the runway, exhibiting classic signs of pilot-induced oscillation (PIO), which made it difficult to control. Eventually, Haise and Fullerton managed to land the vehicle and bring it to a halt, but the results of the flight were mixed. While the orbiter had landed, unpowered, on the runway as planned, the unexpected PIO was a significant concern and a potentially dangerous consequence for shuttles returning from space.

Engineers at Dryden went to work on the problem, attempting to figure out what caused the PIO and how to prevent it during future flights. They concluded that there was a glitch in the shuttle’s computerized control system: a delay between human input and computer response that, while only about 270 milliseconds, increased the likelihood of PIO during landing. Engineers went on to explore the problem in the F-8 Digital Fly-By-Wire program, which utilized the same flight control computer as the shuttle. Engineers were able to recreate the PIO problem seen with Enterprise and then develop a software filter to suppress it.

The ALT established that the space shuttle was able to approach and land precisely, without air-breathing engines, after reentry into Earth’s atmosphere. It also validated the onboard control systems for the orbiter. And with the solution for the flight control computer that came out of the F-8 Digital Fly-By-Wire program, the shuttle flight tests were declared a success.

Despite the success of the ALT, Enterprise never flew freely again. Originally, the shuttle team intended to update Enterprise with thermal protection, a propulsion system, and other components that would enable it to fly in space and serve as the program’s second orbiter. However, a last-minute design change to Columbia rendered Enterprise obsolete. Following the ALT, Enterprise was ferried by the SCA to Marshall Space Flight Center for structural tests and later to Kennedy Space Center for further ground-based testing. The next time a shuttle flew was on April 12, 1981, when Columbia blasted off from Cape Canaveral for STS-1.

Watch a video of the final ALT landing on the runway at Edwards Air Force Base, in which Enterprise visibly experienced PIO.

Read APPEL News articles about the start of the Lifting Body Program and the end of the program.

Read an APPEL News article about the F-8 Digital Fly-By-Wire program.