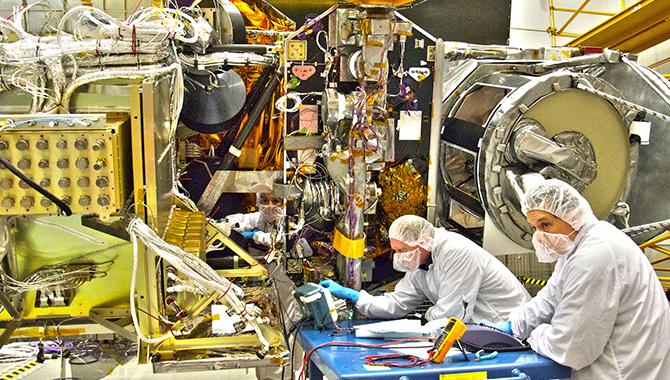

The team who developed the Dellingr CubeSat discussed their experiences designing, testing, and delivering the project on a tight time frame at a fraction of the cost of a traditional satellite.

Credit: NASA

A recent Virtual Project Management Challenge presented lessons learned and best practices for achieving big results from small projects.

Although NASA is best known for successfully accomplishing some of the largest, most complex engineering and science feats in human history, the agency has far more small projects underway at any given time. And the engineers and managers who lead these small projects understand that they bring unique complexities and challenges.

How best to manage those complexities and challenges is the subject of a Virtual Project Management Challenge that APPEL Knowledge Services presented in June. One of the guests on “Smaller, Faster, Better: Big Lessons from Small(er) NASA Missions” was David Wilcox, chief of the Special Projects Office at NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility.

Also, key members of the team that developed the Dellingr CubeSat were guests. Dellingr has been described as “a potentially disruptive technology that gives us a way to dramatically change the way we do science.”

Chuck Clagett, Dellingr project manager, Luis Santos, Dellingr deputy project manager, and Larry Kepko, Dellingr project scientist, all from the Goddard Space Flight Center, discussed their experiences designing, testing, and delivering Dellingr on a tight time frame at a fraction of the cost of a traditional satellite.

Dellingr was developed under a “Do No Harm” risk classification, as are many smaller NASA projects. This classification accepts a very high level of technical risk and has no life expectancy requirements. This classification provided the team with greater latitude during the project, enabling them to utilize nontraditional analysis tools, for instance, to be nimble during development and testing.

As the guests shared their experiences on smaller projects, a common set of best practices emerged. For example, managing stakeholder expectations is important in order to resist a natural tendency for a small project team to be pressured to adhere to a higher risk classification standard, especially during gateway reviews.

Another key to managing a small project, Wilcox said, is to encourage the development of a systems engineering mindset, with everyone on the small team considering the big picture in addition to their specific job function. “Ideally, everybody on a small project team … knows a little bit about what everybody else is doing. … They’re not off in their own swim lane by themselves.”

Forming a cohesive team is another important aspect, especially because working on a particular small project might represent a only fraction of each team member’s overall work time. Given the focus on fostering a systems engineering mindset among all team members, co-locating the team is ideal. If that isn’t possible, however, the experts suggest bringing everyone together for intensive, multiple day work sessions at the beginning of the project and periodically thereafter, as the budget allows.

“I think that it’s important up front to establish relationships. What’s been successful for us in the past on a couple of previous projects is scheduling co-location events,” Wilcox said. “Then, the rest of the time, when everyone goes off to their home locations, take advantage technology, [such as virtual meetings].”

If the team members have served different roles in other small projects, that will enhance the development of a systems engineering mindset and make the team stronger. They can also mentor younger team members or serve as backups for other roles. However, having one team member serving in multiple roles on a single small project—as for instance deputy project manager, systems engineer, and mechanical engineer—can create challenges if that team member is pulled away onto another project and must be replaced.

“It’s a tremendous advantage if you have a person who has done those three jobs,” Wilcox said. “You don’t necessarily want them doing all three jobs on your project [at the same time]. You don’t want to have a team of three people where each person is doing four jobs.”

To watch this informative Virtual Project Management Challenge and learn more about the complexities and challenges of smaller projects at NASA, click Smaller, Faster, Better: Big Lessons from Small(er) NASA Missions.

To receive email notifications about upcoming NASA Virtual PM Challenge sessions and recorded session availability, please subscribe to the Virtual PM Challenge email list.