On the set of the November 15th Virtual Project Management Challenge. From left to right: Host Ramien Pierre, Thomas Zurbuchen, and William Gerstenmaier. Credit: NASA

Leaders with decades of high-profile experience on NASA’s largest projects discuss the importance of good culture, open communication, and realistic expectations to mission success.

NASA’s large projects—from humans on the moon, to rovers on Mars, to probes in the Kuiper Belt—have dramatically expanded the boundaries of human achievement. Managing these projects, however, is still very much a human endeavor in which a good culture, open communications, and a solid understanding of the challenges ahead are critical to mission success.

On November 15, 2018, APPEL Knowledge Services presented a special episode of the Virtual Project Management Challenge (VPMC) with guests William H. Gerstenmaier, Associate Administrator of NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate, and Thomas Zurbuchen, Associate Administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate.

“This installment of our VPMC series was filled with valuable insights and advice for every project team member, particularly program and project managers and those who aspire to that role in their careers,” said Roger Forsgren, NASA’s Chief Knowledge Officer and Director of APPEL Knowledge Services.

Gerstenmaier and Zurbuchen, both with decades of high-profile experience on NASA’s largest projects, discussed six Lessons Learned from Large NASA Projects.

While touring the Space Station Processing Facility at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Thomas Zurbuchen, in plaid shirt, NASA’s Associate Administrator for the Science Mission Directorate, learns about the advanced habitat used to grow plants in space.

Credit: NASA

Lesson 1: Focus more on people to prevent mistakes and their consequences. Good people and culture are essential. Procedures and processes alone are not sufficient.

The processes NASA uses to manage large projects will provide a manager with a great deal of important information. However, a team’s interpersonal connections are nuanced and complex. Time spent on the floor with a team reveals the natural leaders. It can also help a manager uncover trouble spots early.

“I love meeting people. Yesterday, I spent time on the floor with technicians of one of our big flagship missions. And what I do there is I basically ask, ‘How are you doing?’ Frankly, what the person says is probably ‘very good,’ but I’m watching. I also ask, ‘Hey, in the last week or so, … what’s the most important challenge you had?’ for example,” Zurbuchen said.

“… There’s the formal way of doing program project management, and we can’t neglect that and forget the formal things that we need to go do. The standards are there, the processes are there. Those are all really important to follow,” said Gerstenmaier. “Don’t treat it as a cold system that you just look at with just hard metrics. … Look under the hood, interact with the people, interact with the program project managers so you really know what’s going on with the program or project.”

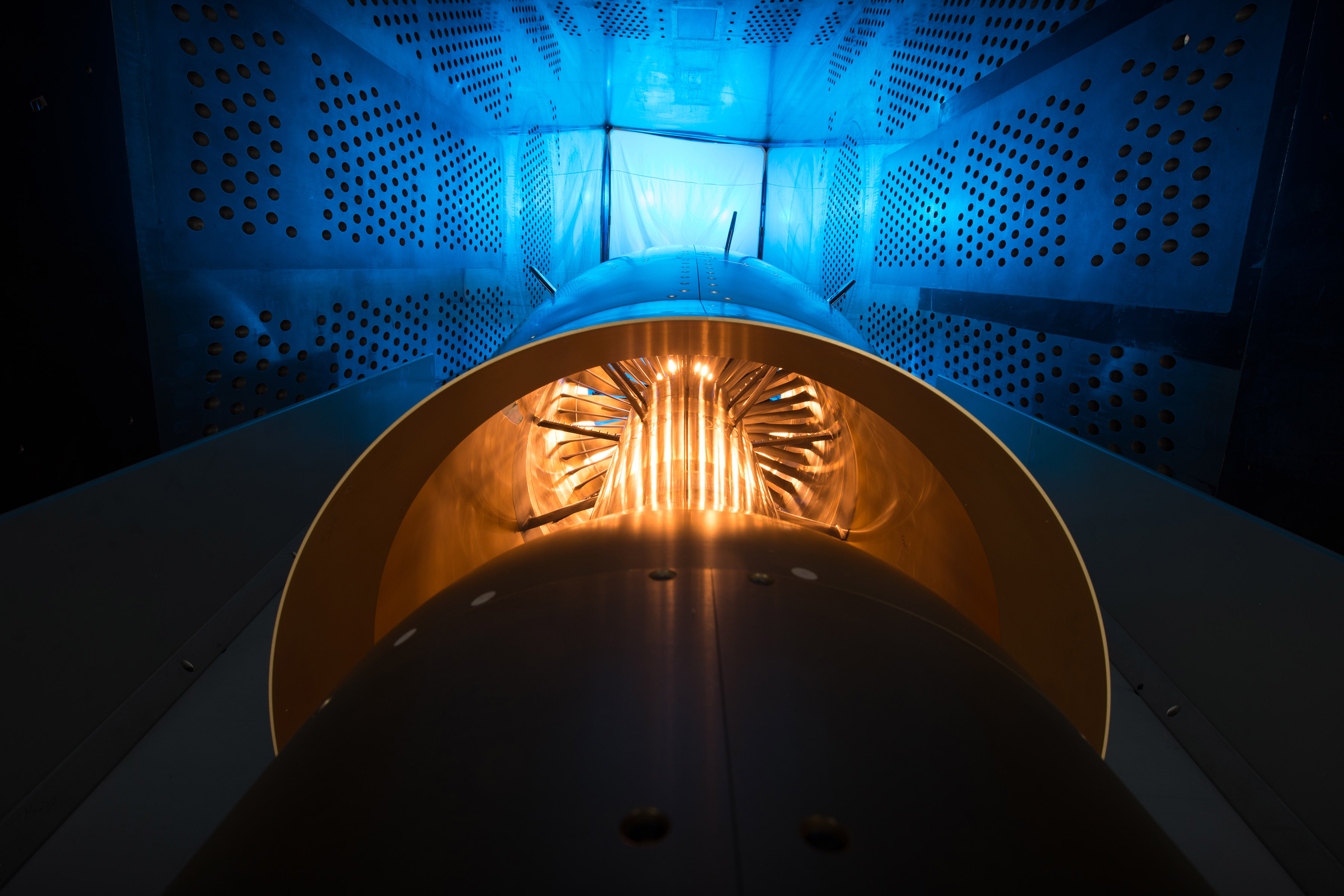

William H. Gerstenmaier, now Associate Administrator of NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate, examines a model of the Space Shuttle in the wind tunnel at Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, earlier in his career.

Credit: NASA, 1978

Lesson 2: Re-evaluate how we assess the development of flagship missions at various stages. The standard review process may not be uniformly effective for all large, multidecadal projects.

For the longer and more complex NASA projects, a standard review might not fully capture the nuances of its development through the many phases toward mission success. This is when a program or project manager can benefit from using more scrutiny, encouraging dissenting opinions, and recognizing the management approach that works in one phase, might not work in the next.

“…Building teams that are as one is a really positive thing. Building scrutiny that comes from diversity of opinions, positive tension—that’s how we talk about it also—is another thing that’s just as important. We want to make sure before we believe everything we say, we actually scrutinize it. Is it actually possible, and so forth?” Zurbuchen said.

And, as the project moves from requirements review, through design review, through manufacturing, a manager might need to adopt different styles to remain fully effective. “…Throughout those various cycles, there’s tools that are more effective in one phase that are not maybe quite as effective in other phases,” Gerstenmaier said. “So, I think you need to adapt your management style and be aware that your project is changing through these phases and look for different ways of doing business.”

Lesson 3: Realistically account for assembly, integration and testing (AI&T). The most time-efficient schedule is likely not robust enough to survive the reality of learning and development that occurs during AI&T.

Managers need to realize that AI&T is not only a complex process, it is still part of the development process in that it’s when a team learns if their systems function properly with one another. What looks great on a paper schedule might not reflect the time needed to resolve AI&T anomalies. Managers can include holds and downtime into the schedule to serve as a buffer. If work slips in an earlier phase, it won’t impact a later one. Also holding some budgetary reserves until the end of the project can help a team meet later challenges.

Gerstenmaier offered the example of the Orion project, which is about to enter a 400-day phase of 24 hours a day, seven days a week work to integrate the service module, supplied by EAS, with the capsule, supplied by NASA. “…This 24/7 thing works really great on paper. I mean, it gives you the most efficient way to get through this entire sequence. But reality is, stuff is going to break.” So, the team is working to include breaks into the period, to act as a buffer.

The Parker Solar Probe, on its way to the Sun, is also a good example of realistically accounting for AI&T complexity, Zurbuchen said. The managers held nearly half of the budgetary reserves for the end of the project, which meant they could have even moved the launch window, if it had been necessary. “I thought that was really wise,” he said, because it created increased scrutiny early in the project to solve issues with hard decisions rather than money.

Lesson 4: Recognize that first-time build challenges are inevitable. New technologies and their risks tend to interact as systems that can’t be fully characterized in the initial development process.

First-time builds are going to contain unforeseen challenges when multiple new technologies interact, because it’s not N new technologies, but rather N–squared interfaces. “So, what happens is the unknown of this technology starts driving the other technology; and all of a sudden, even though in a box they work just fine, in a system they don’t,” Zurbuchen said.

Gerstenmaier said that because many of NASA’s large projects are one-offs, a manager should factor in complications, such as access that looks good in the CAD program, but isn’t really there when the builder is assembling the project. “So, I think you just [have] to factor that in and not be discouraged when that’s occurring.”

Just like drivers sometimes use snow to clean their car mirrors in winter, two Exelis Inc. engineers are practicing “snow cleaning'” on a test telescope mirror for the James Webb Space Telescope at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Credit: NASA/Goddard/Chris Gunn

Lesson 5: Establish a culture of transparent and open communication at all levels. Management needs to continually and intentionally work to create an environment where concerns and issues can be shared up, down and across reporting chains.

A manager needs to push the team to great accomplishments on a large NASA mission, but not so hard as to create a stifled environment in which team members are reluctant or unwilling to discuss bad news early and openly. An engineer working quietly on an unknown problem, rather than bringing it to the manager, can create an opportunity cost for the entire project.

“Yeah, we want to perform but also have the right culture,” Zurbuchen said. “There’s simple ways of killing that culture, and that is the first one who walks into your office with bad news gets killed right there. Right? You basically go at them, scream at them… I get a lot of bad news, right? But the vast majority of these bad news items never materialize. And also, the ones that do, it’s important to hold back.”

“If somebody brings me a problem, I try to evaluate a little bit whether I think that problem could be maybe solved in a different way if I opened it up to a broader group,” Gerstenmaier said. “But in some cases that problem is totally within the [wheelhouse] of the engineer. So, then I don’t want to take that problem away from the engineer. I just recognize that he or she has this problem that they’re going to work on and I let them go work it.”

Lesson 6: Ensure oversight is organized and staffed appropriately at each phase of mission development. Effective oversight requires both “positive tension” and a mix of “in-depth” and “30,000-foot” views.

The key to effective oversight is finding a mid-point at which the standing or independent review board is neither an advocate for the program nor a policeman, scouring for minor infractions. Staffing the review board with other project managers is an effective technique.

“Because now the program project manager is being looked at by another program project manager, and that one [who’s] running the independent review board is looking for ‘how could I really help this other program or project?’ ” Gerstenmaier said.

“The standing review board, like any other of these human activities we just talked about, needs to be managed in a way that we actually get independent thought,” Zurbuchen said. “We get scrutiny. We get that positive tension that we talked about. … Having served on some of these external reviews, you know, you learn so much so fast.”

The November VPMC, Lessons Learned from Large NASA Projects is available here for on-demand viewing.

“There is great value for all program and project managers in this VPMC. I’d like to encourage all members of NASA’s technical workforce to view this episode,” Forsgren said.

Want to share these lessons with your team? Here’s a summary: Lessons Learned from Large Projects.