STS-49 crew poses for group portrait. Daniel C. Brandenstein, center, is mission commander; and Kevin P. Chilton, third from right, is pilot. Mission specialists are, left to right, Kathryn C. Thornton, Bruce E. Melnick, Pierre J. Thuot, Thomas D. Akers and Richard J. Hieb.

Credit: NASA

The Shuttle performed flawlessly in a difficult mission to capture and repair satellite.

Space Shuttle Endeavour launched on its first flight, STS-49, 28 years ago this month on May 7, 1992. Endeavour was the fifth and final Space Shuttle NASA built. The name was in recognition of the HMS Endeavour, a ship that British explorer James Cook used to navigate the South Pacific Ocean from 1768-1771, exploring the coasts of New Zealand and Australia. The name was suggested through a contest.

NASA incorporated updated avionics and auxiliary power units into Endeavour, as well as other upgrades to enable the shuttle to accommodate missions as long as 28 days. Daniel C. Brandenstein, Commander of STS-49, recalled that although Endeavour was slightly lighter than earlier Shuttles and included a drag chute for landings on shorter runways, the flying experience and basic systems were the same.

“…You strive to keep the vehicle as similar as possible,” Brandenstein recalled in an oral history. “It makes the training easier… They built a beautiful vehicle. It was really nice that the Endeavour performed like an old pro.”

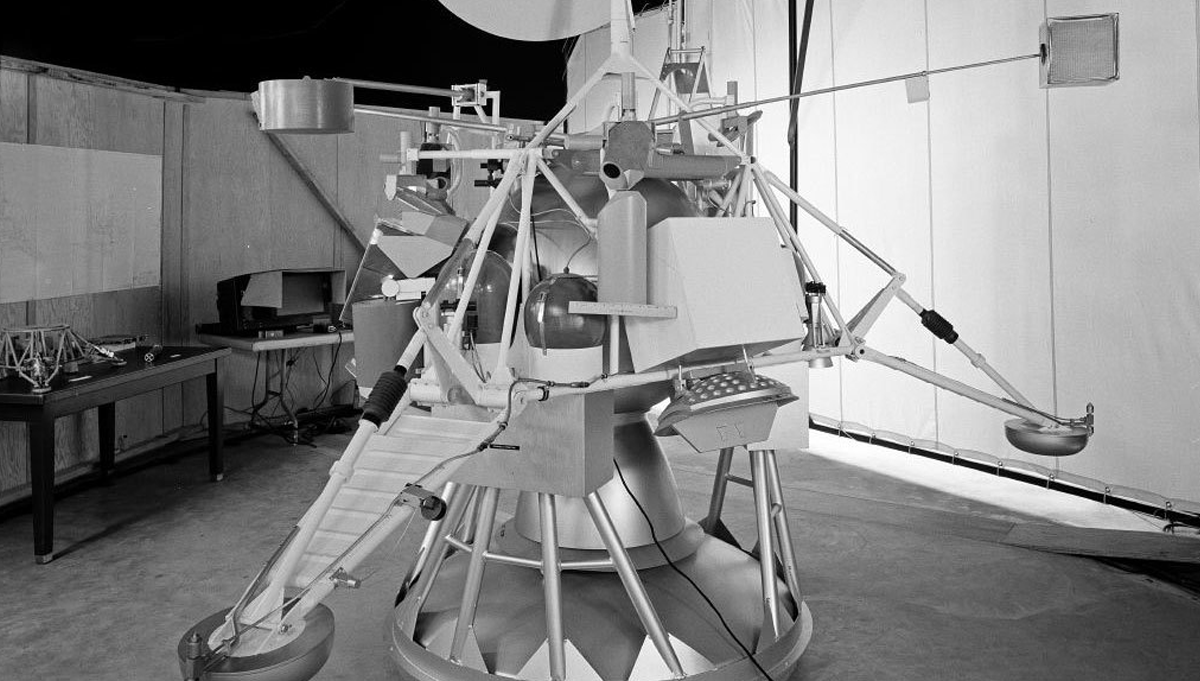

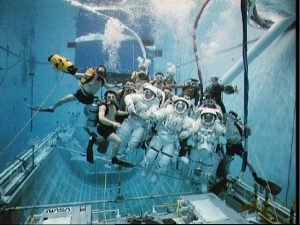

Simulation at JSC’s Weightless Environment Training Facility was conducted with extravehicular mobility unit suited astronauts F. Story Musgrave, Michael R. U. Clifford, and James S. Voss.

Credit: NASA

It was helpful that the Shuttle performed well, because the crew faced a major challenge with one of the primary objectives, retrieving Intelsat 603, a communications satellite that launched atop a Titan III rocket in March 1990. In space, the satellite wouldn’t release from the second stage of the Titan III. Eventually, flight controllers jettisoned the perigee motor to free the satellite, but that left the satellite with no means to enter the proper geostationary orbit.

The Endeavour crew practiced the retrieval process extensively during their training. Mission Specialist Pierre J. Thuot was to place a special capture bar onto a structural element of the satellite, latch it into place, then work with Mission Specialist Richard J. Hieb to attach the satellite to the Shuttle’s mechanical arm and retrieve it. The crew was then to fit the satellite with a new perigee motor and return it to space.

“From day one, my concern was that if we bump it and it doesn’t latch, is it going to be difficult or impossible to catch?” Brandenstein recalled. His concerns were eased by the training Thuot and Hieb performed on what is known as an “air bearing floor,” which uses compressed air to simulate what it is like to move objects in space. When their training was complete, both Thuot and Hieb could attach the capture bar proficiently.

“But, you know, you’re training in 1 G, and there’s some artificialities associated with that when compared to what’s really happening in zero gravity,” Brandenstein said.

The first EVA to capture the satellite ended after several attempts in which Thuot aligned the capture bar to the structural element, but the latches didn’t secure the two together. And, as Brandenstein suspected, the attempts had sent the satellite drifting at a rate that ruled out further attempts during that EVA.

“That was a pretty low point,” Brandenstein recalled, “because when we left, it had a pretty good rate on it, and it was kind of flat spinning and stuff. We thought we’d lost this 150 million, 200 million-dollar satellite, you know, and you don’t like that to happen. … So, we got [Pierre] back and Rick back inside and flew away and got some distance on it.”

Intelsat flight controllers, however, were able to gain control over the satellite, meaning the crew of STS-49 would have a second chance. After the second EVA also ended with multiple, unsuccessful capture attempts, Brandenstein recommended that the crew take a day off from the recapture efforts to weigh options.

Left to right, astronauts Richard J. Hieb, Thomas D. Akers and Pierre J. Thuot, cooperate on the effort to attach a specially designed grapple bar underneath the satellite.

Credit: NASA

“…I was convinced—the crew was convinced, for that matter—that we had done, with the tools we had and the procedure we had originally developed, that we had done it as well as it could be done, and it still didn’t work,” Brandenstein recalled.

During the day off, the entire crew, which included Pilot Kevin P. Chilton and Mission Specialists Bruce E. Melnick, Kathryn C. Thornton, and Thomas D. Akers, brainstormed ideas, looking out the window into the payload bay. The next morning, they showed their solution, which was sketched on a piece of paper and placed in front of a TV camera, to mission control.

The solution involved the first three-astronaut EVA. The astronauts would all simultaneously grab the satellite by hand, and once it was controlled, attach the capture bar. Then the mission would proceed as planned. As mission control worked through the procedures to move three people through the Shuttle’s airlock, Brandenstein had the crew put on spacesuits and work with the actual airlock on Endeavour.

“Turned out that both answers came out the same, that, yes, it could be done,” Brandenstein recalled, adding that the crew had already worked through the safety concerns they could foresee and developed contingency plans for what they thought could go wrong. During the night, mission control fine-tuned where the astronauts would be positioned and developed procedures.

And so, Brandenstein, a veteran astronaut on his fourth and final Shuttle mission, guided Endeavour in a record third rendezvous of the mission, moving inch by inch, to align the Shuttle with the satellite. When they were in position, Thuot, Hieb, and Akers counted to three, reached out, and secured the 4.5-ton communications satellite by hand and attached the capture bar. At 8 hours and 29 minutes, it was NASA’s longest EVA to date. The astronauts attached the new perigee motor and the satellite was successfully redeployed.

Endeavour returned to Earth on May 16, landing at Edwards Airforce Base. It would go on to fly 24 more missions, including STS-61, the first servicing mission to repair the Hubble Space Telescope. Endeavour was also used on missions to build the International Space Station, including delivering the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer. Endeavour is on display at the California Science Center in Los Angeles.