The Space Shuttle Discovery launches on its first flight, STS-41-D, on August 30, 1984, 37 years ago this month. The crew deployed three satellites and heard knocking at the payload bay doors.

Credit: NASA

Crew deploys record number of satellites, hears knocking at the door.

In the early hours of August 30, 1984, 37 years ago this month, the crew of STS-41-D prepared for the first launch of NASA’s newest space shuttle, Discovery. Ahead of them was the 12th orbital flight of the shuttle program, a six-day mission in which they would deploy a then record three satellites, perform several key science experiments, and respond to a mysterious knocking at the payload bay doors when the shuttle was 184 statute miles above Earth.

Discovery was NASA’s third orbiter. It weighed nearly 7,000 pounds less than Columbia, primarily because about 6,000 white ceramic tiles had been replaced in strategic locations by Advanced Flexible Reusable Surface Insulation, a high-performance quilted, ceramic insulation blanket.

August 30 was the fourth time the crew, led by Commander Henry W. Hartsfield, Jr., had strapped into Discovery, ready to go to space. On June 26, Discovery had come within six seconds of launch when two of the main engines abruptly shut down after the shuttle’s computers detected an anomaly in the third engine, which hadn’t ignited. To add to the tension, soon equipment at the launchpad indicated there was a fire on the launchpad.

“That got everybody excited, and they wanted to get us out of there in a hurry,” Hartsfield recalled in an oral history. “The trouble with a hydrogen fire is you can’t see it. You know, hydrogen and oxygen burn clear, and you can just see some heat ripples when you’re looking through it, but you can’t see the flame.”

The crew assigned to the STS-41D mission included (seated left to right) Richard M. (Mike) Mullane, mission specialist; Steven A. Hawley, mission specialist; Henry W. Hartsfield, commander; and Michael L. (Mike) Coats, pilot. Standing in the rear are Charles D. Walker, payload specialist; and Judith A. (Judy) Resnik, mission specialist.

Credit: NASA

The fire suppression system at the launchpad was activated. Discovery was returned to the Orbiter Processing Facility for an engine replacement. With Discovery’s launch delayed by two months, STS-41-F was cancelled, and its payload shifted to STS-41-D. After a flight software issue forced an August 29 launch attempt to be scrubbed, the launch on August 30 went smoothly. The pilot was Michael L. Coats, making his first spaceflight.

“I remember we tried to launch four times. We climbed in four times before we finally launched,” Coats recalled in an oral history. “My first launch, it was a blur. You’re glad that you are trained to a fine edge, if you will, because if something happens, you react automatically. That’s what you’ve been trained to do. So, you don’t have to think about it a whole lot, and that’s a good thing.”

On orbit, the crew of STS-41-D— Mission Specialists Judith A. Resnik, Steven A. Hawley, and Richard M. Mullane and Payload Specialist Charles D. Walker—went right to work. Mulane and Resnik deployed the satellites, one each on the first three days. The Satellite Business System SBS-D was deployed on day one. Capable of handling 1,300 simultaneous telephone calls, it was the fourth in a series of corporate communications satellites.

The SYNCOM IV-2 satellite released on day two was the first designed especially to be deployed by the space shuttle. It became part of a system utilized by the U.S. military. The TELESTAR 3 deployed on day three was part of a new generation of satellites to service the growing telecommunications industry.

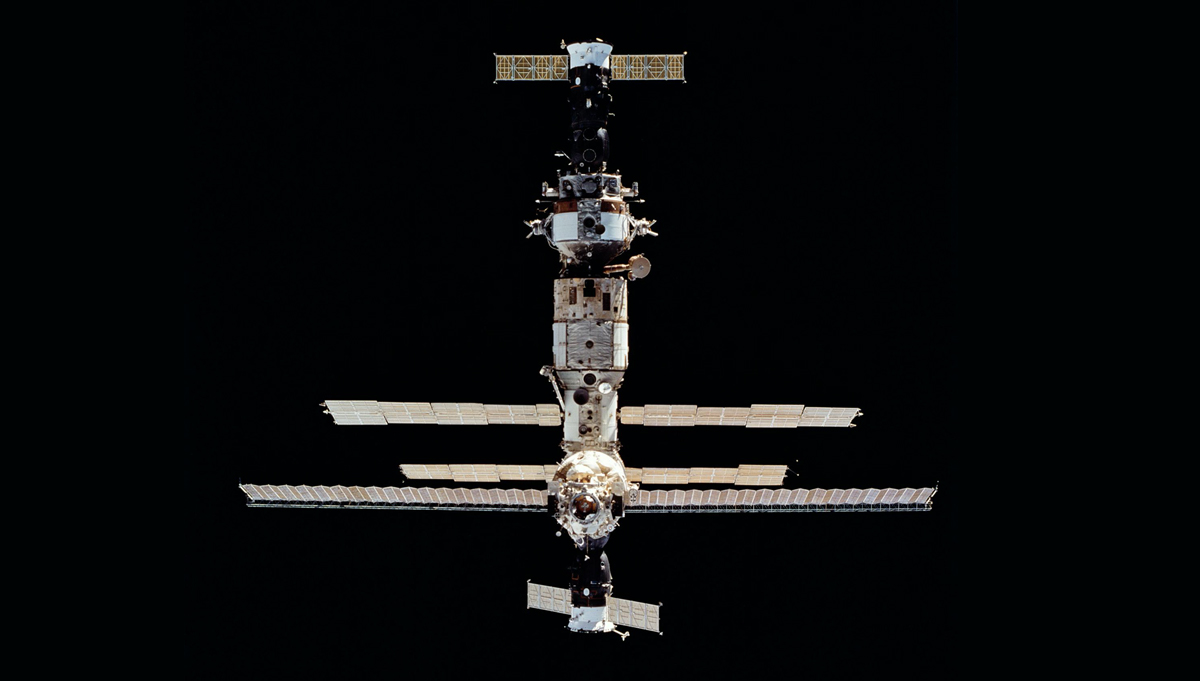

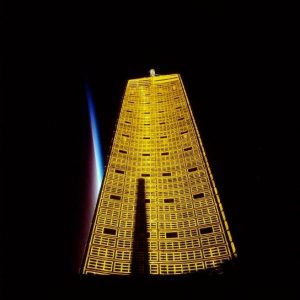

Resnik, who became the second American woman in space with the flight, was responsible for testing the Office of Application and Space Technology solar wing (OAST-1), a large, flexible solar array that deployed 102 feet above Discovery’s payload bay. Resnik extended and contracted the 13-foot-wide solar wing multiple times—a first in space—to demonstrate the wing’s performance, structural dynamics, and rigidity. The results would inform the design of solar arrays for the International Space Station.

The Office of Application and Space Technology solar wing (OAST-1), extends 102 feet above Discovery’s payload bay. The tests demonstrated the wing’s performance, structural dynamics, and rigidity.

Credit: NASA

Because the crew member’s days involved a lot of solo work on tight schedules, Hartsfield said he “decreed” that the evening meal would be eaten together as a group. “I want one time for the crew to just get together and just chat and have a little fun and say, ‘Okay, where are we? What have we got to do tomorrow?’ and talk about things.”

It was during one of these meals that the crew heard knocking at the right side of the orbiter.

“What in the world? It sounded like somebody was knocking to get in, you know?” Hartsfield recalled.

“We’re on the night side of the Earth, so it’s pitch-black outside. We had a traffic jam getting up into the hatch end of the flight deck. The rapping was coming from the starboard side … It wasn’t the side the hatch was on, which was kind of a relief. [Laughter] But we couldn’t figure out what it was.”

Hawley traced the knocking back to the KU band antenna, on a gimbal mount at the starboard seal, aft of the bulkhead. He turned it off and recycled the antenna. By the time it powered up again, the shuttle was at a different angle to the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite, and the knocking stopped.

“At the time, it really got our attention, you know. I mean here we are in the middle of space, and somebody wanting in, you know, is what it sounded like. We got a big laugh about that,” Hartsfield recalled.

STS-41-D returned to Earth on September 5, 1984, landing at Edwards Air Force Base. Hartsfield went on to serve as Commander of STS-61-A. Coats went on to command STS-61-H, STS-29 and STS-39. The incident at the launchpad on June 26 prompted changes in safety procedures for fires at the launchpad and brought about the first human testing of the launchpad’s Emergency Egress System, which sent astronauts in baskets down a slidewire to safety.

To learn more about STS-41-D and all 135 space shuttle missions, please visit APPEL Knowledge Services’ Shuttle Era Resources page.