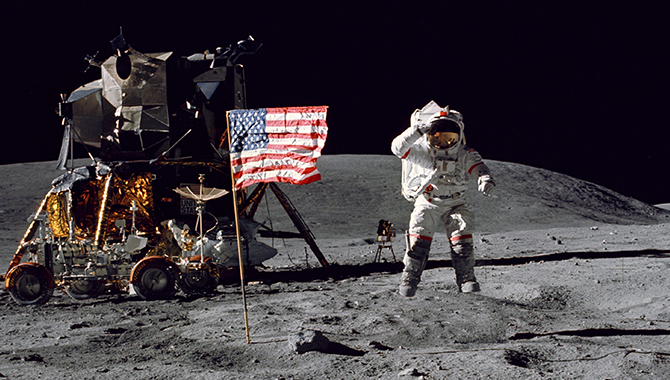

Shown here in 2017, the site for what is now the Johnson Space Center was selected from a list of 23 cities in September 1961. It was chosen for its key attributes, including moderate climate, established industrial complex, and ready access to water transportation that could accommodate massive barges. Credit: United States Coast Guard

The Space Task Group moves west and becomes the Manned Spacecraft Center.

By late summer, 1961 was shaping up to be a year of success and promise for NASA. On May 5, Alan Shepard blasted off in a Mercury spacecraft paired with a Redstone Launch Vehicle to become the first American in space. And although cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had become the first human in space about three weeks earlier, Shepard was the first human to control a spacecraft in space. Gagarin’s Vostok spacecraft was controlled from the ground.

Later in May, President John F. Kennedy gave NASA a huge vote of confidence when he addressed a joint session of Congress, asking for a significant increase in funding—$531 million immediately and as much as $9 billion more over the next five years—to land humans on the Moon and bring them safely home.

In July, Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom became the second American in space. His flight in a Mercury spacecraft paired to a Redstone Launch Vehicle was also a success, although his capsule sank after splashdown. With development of the new, more powerful, two-stage Atlas LV-3B Launch Vehicle nearing completion, the Agency had an orbital mission clearly within reach.

In August 1961, fresh off those successes, and with a goal so bold it would require towering achievements in engineering, science, and production to accomplish, NASA Administrator James Webb appointed a team to visit far flung sites from Tampa, Florida, to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to San Diego, California, and Houston, Texas to find a suitable site for a new central hub of human space exploration.

Director of the Space Task Group Robert Gilruth (second from left) with, from left to right, chief assistants Charles Donlan, Maxime Faget, and Robert Piland. Here, these original members of the Space Task Group discuss contractors to study feasibility of a manned circumlunar mission. August, 1960.

Credit: NASA

The search was prompted by the growing realization that NASA’s Space Task Group, headed by aerospace engineer Robert R. Gilruth, would need to expand dramatically and bring together the growing number of engineers and scientists working to develop the technology to reach the Moon. In NASA’s $1.7 billion budget for 1962, Congress included $60 million—the equivalent to about $520 million in 2020—for development of what would become known as the Manned Spacecraft Center.

In August 1961, Webb’s site-selection team, which included administrators and construction engineers, began with a list of cities and exacting criteria. The new site must have a moderate climate, an established industrial complex with an adequate labor pool, robust commercial jet service, strong water and electric utility infrastructure, access to water transportation that could accommodate massive barges, and a culturally attractive community in the vicinity of an institution of higher education to help NASA attract and retain top talent.

As exacting as those criteria were, there was no shortage of candidate sites for what was destined to become a powerful economic engine for the selected city. The team started with a list of 22 cities and reduced that to 9, only to have 14 additional sites added. The team then toured 23 sites, many near significant military bases, before identifying its first choice—Tampa, Florida.

The U.S. Air Force was planning to close a major portion of MacDill Air Force Base, about eight miles south of Tampa on the Interbay Peninsula, leaving a site that nicely met all the criteria. But, before the team could make its recommendation, tensions with Cuba prompted the Air Force to reverse that decision.

And so, the team’s second preference became their first recommendation to Webb. On September 14, 1961, 59 years ago this month, Webb informed President Kennedy that he and deputy administrator Hugh Dryden had chosen a site for the new Manned Spacecraft Center.

“Our decision is that this laboratory should be located in Houston, Texas, in close association with Rice University and the other educational institutions there and in that region,” Webb wrote. The decision was announced to the public on September 19, 1961.

Rice University conveyed as a gift the bulk of the site for the new Center—1,000 acres of cattle pasture southeast of Houston near Clear Lake off Galveston Bay, with an additional 20-acres of reserve land. The university had earlier received the land as a donation from the Humble Oil company. The federal government purchased an additional 600 acres to give the new center frontage to a local highway.

With the decision made, NASA began leasing temporary office space in the Houston area, eventually reaching nearly 300,000 square feet as construction began in 1962 on the new center. By the time construction was complete and the center opened in September 1963, NASA had already completed Project Mercury and turned its attention to Project Gemini and Apollo.

The new center quickly became a bustling hub, playing a critical role in the mission to land humans on the Moon. Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong recalled, in an oral history, “When I was working here at the Johnson Space Center, then the Manned Spacecraft Center, you could stand across the street and you could not tell when quitting time was, because people didn’t leave at quitting time in those days. People just worked, and they worked until whatever their job was done… So, four o’clock or four-thirty, whenever the bell rings, you didn’t see anybody leaving. Everybody was still working.”