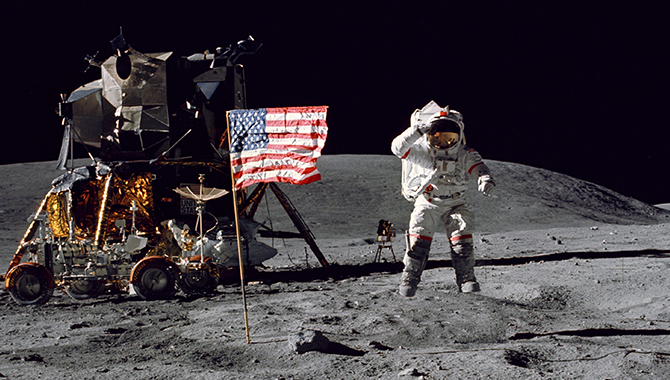

Apollo 16 Commander John W. Young salutes the United States flag during the mission’s first extravehicular activity, with the Lunar Module and the Lunar Roving Vehicle in the background. Lunar Module Pilot Charles M. Duke, Jr. took the photo.

Credit: NASA

Mattingly, bumped from Apollo 13, finally orbits the Moon as Apollo nears the end.

On April evenings in 1972, Thomas K. Mattingly II, trying to stave off the boredom of prelaunch isolation, would drive to launch pad 39A at Kennedy Space Center. The Saturn V rocket towering 363 ft above him, 33 ft in diameter at the base, was nearing completion. It would launch him, John W. Young and Charles M. Duke, Jr. toward the Moon on April 16. After spending years learning the controls of the Apollo Command Module, he realized he didn’t know much about the rocket.

“Wasn’t necessary. You’re not doing anything except [sitting] there,” Mattingly recalled, in an oral history. “But, it was kind of a cool thing that I just wanted to see.” Mattingly even introduced himself to a startled technician one night, who happily explained the late work he was doing by flashlight in the instrument unit, which housed the guidance and electronics atop the Saturn V, still the most powerful rocket ever launched.

From left to right, Thomas K. Mattingly II, command module pilot; John W. Young, commander; and Charles M. Duke Jr., lunar module pilot.

Credit: NASA

Mattingly had been this close to launch before, as the Command Module Pilot for Apollo 13. Duke, who was on the backup crew for that mission, contracted measles the week before launch and unknowingly exposed both the backup crew and the primary crew. Mattingly was the only other member of either crew who didn’t have immunity. NASA determined that the risk of Mattingly developing measles and falling ill while orbiting the Moon alone in the Command Module was too great and replaced him with Jack Swigert just days before the launch.

It was shortly after Apollo 13 was saved that Deke Slayton, Director of Flight Crew Operations, offered Mattingly the opportunity to serve as either the Command Module Pilot on Apollo 16 or the Lunar Module Pilot on Apollo 18, advising him to consider the value of a “bird in the hand.”

“I concluded that I really wanted to go to the surface, but it probably was better to get near it than not go at all,” recalled Mattingly, who didn’t contract measles from his exposure. Apollo 18 was later canceled.

Apollo 16 was the “bird in the hand,” and it launched at 12:54 p.m. EST on April 16, arriving at the Moon three days later. It was the fourth spaceflight in Young’s accomplished career as an astronaut, which spanned 42 years, from Gemini III and STS-9. He was the ninth person to walk on the Moon and the first Commander of a Space Shuttle mission, STS-1.

It was Duke’s only spaceflight and it made him the tenth person to walk on the Moon. He became an astronaut in 1966 as a member of NASA’s fifth group. He famously served as CAPCOM during the Apollo 11 Moon landing, as Neil Armstrong ran low on fuel searching for a suitable landing spot. After Apollo 11 landed, Duke said, “You’ve got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

Apollo 16 benefitted from the lessons learned from previous missions but faced new challenges. The most significant came after the Command Module (CM) and the Lunar Module (LM) separated. An hour before Young and Duke were to land the LM, Mattingly was to burn the Service Propulsion System to put it into proper position in case the landing had to be aborted.

“Well, he reports a real problem in the engine,” Duke recalled in an oral history. When Mattingly powered up the system, it began to oscillate. “… it wouldn’t stabilize the engine and it was wiggling back there. And he thought that the thing was going to shake him apart.”

“If your heart can sink to the bottom of your boots in zero gravity ours did, because … there we were, you know, 2 years of training, 240,000 miles away, an hour before the landing on an orbit you can look down at your landing site, 8 miles beneath you, and they’re about to tell you to come home,” Duke recalled. “And that’s what we thought was going to happen because it was, according to Mission Rules, abort.”

Mission Control worked on the issue for several hours before telling the crew they had successfully isolated the cause and could work around it, giving Young and Duke the go ahead to begin their descent.

Panorama view of Apollo 16 commander Astronaut John W. Young, working at the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) just prior to deployment of the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP) during the first moonwalk of the mission on April 21, 1972.

Credit: NASA

Apollo 16 made a soft landing on the lunar surface more than five and a half hours behind schedule at 9:24 p.m. EST. Young and Duke were on the Moon for 71 hours, spending 20 hours and 14 minutes outside the LM, divided over three EVAs. The mission was the second to include a Lunar Roving Vehicle, which Young and Duke used to explore an area known as the Descartes Highlands, surrounding the massive Descartes crater, 29 miles in diameter and more than half a mile deep. They traveled a total of 16.6 miles on the lunar surface and collected 209 pounds of samples.

Mattingly, who had nearly turned down the Command Module Pilot position, was happy he’d taken Slayton’s advice years earlier. “… I can neither explain why nor explain the sensation, but the exhilaration of flying that thing solo was as—I desperately wanted to go down and land, but, boy, you really need both. It’s just really too much, and there’s just so much there,” Mattingly said.

On the way back to Earth, Mattingly performed an EVA to collect film from the scientific instrument module and to open a small box containing a science experiment, exposing microbes to the vacuum of space for a controlled amount of time before sealing it again. During the 83-minute deep space EVA, Duke noticed Mattingly’s wedding ring, which he’d lost earlier, floating out the hatch.

“And there was my wedding ring floating out the door. I grabbed it, and we put it in the pocket. We had the chances of a gazillion to one. So, I said, ‘That’s pretty cool stuff, Charlie,’ ” Mattingly recalled.

Apollo 16 returned to Earth on April 27, splashing down in the South Pacific Ocean, where the astronauts were retrieved by the USS Ticonderoga. Mattingly went on to serve as Commander of STS-4, the final test mission of the Space Shuttle Columbia, and STS-51-C.