In this photograph, astronaut Edwin (Buzz) Aldrin takes his first step onto the surface of the Moon.

Credit: NASA/Neil Armstrong

With alarms sounding and fuel running low, Armstrong and Aldrin become the first humans on the Moon.

On a difficulty scale from 1 to 10, landing on the Moon ”was probably a thirteen.” That’s how Neil A. Armstrong recalled, with a chuckle, the July 20 landing of Apollo 11 during an interview by historians and authors Stephen E. Ambrose and Douglas Brinkley for an oral history.

“The most difficult part [of the mission] from my perspective, and the one that gave me the most pause, was the final descent to landing. That was far and away the most complex part of the flight,” Armstrong recalled. “The systems were very heavily loaded at that time. The unknowns were rampant. The systems in this mode had only been tested on Earth and never in the real environment. There were just a thousand things to worry about in the final descent.”

On Earth, the testing hadn’t always gone well. The astronauts flew the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV), a “contrary and risky” machine that nevertheless prepared them well for a Moon landing. Armstrong likened the LLRV to a tin soup can with legs. On May 6, 1968, as he was slowly bringing an LLRV in for a landing, the attitude control rockets faltered less than 100 ft above the ground. He wrestled with the machine as it pitched sideways, but ultimately ejected seconds before it crashed and exploded.

Aldrin, Armstrong and Collins pose in business suits following a press conference at the Manned Spacecraft Center.

Credit: NASA

Armstrong was an accomplished pilot, having flown combat missions during the Korean War, and an X-15 rocket plane to an altitude of 207,500 ft. He was no stranger to adjusting to adversity either, having flown an F9F Panther to safety after six feet of its right wing was sheared off. So, by the summer of 1969, as Armstrong and Lunar Module Pilot Edwin “Buzz” E. Aldrin Jr. descended to the lunar surface, they had as much experience as anyone could have to attempt something that had never been done. And that experience would be tested.

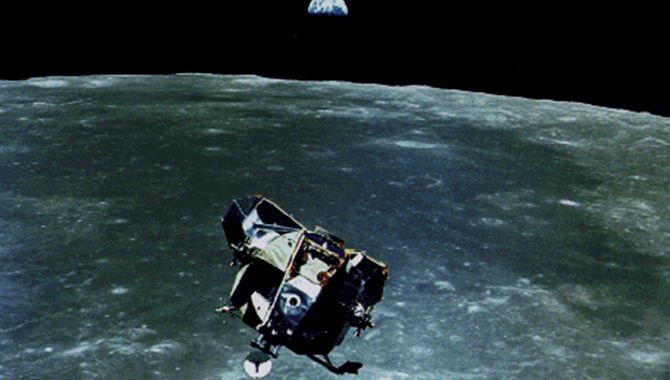

With the Lunar Module—known as Eagle—about 6,000 thousand ft above the lunar surface and descending slightly faster than expected, the guidance computer issued a series of unusual 1201 and 1202 program alarms. Aldrin and Armstrong were unfamiliar with the codes and Mission Control raced to determine if the landing would have to be scrubbed.

“You’re always concerned when any kind of alarm comes on, but it wasn’t a serious concern because there wasn’t anything obviously wrong. The vehicle was flying well, it was going down the trajectory we expected, no abnormalities in anything that we saw…,” Armstrong recalled. “…My own feeling was, as long as everything was going well and looked right, the engine was operating right, I had control, and we weren’t getting into any unusual attitudes or things that looked like they were out of place, I would be in favor of continuing, no matter what the computer was complaining about.”

Armstrong’s confidence came in part from the exacting reliability requirements for Apollo components—many of which were 0.99996. And, in fact, the majority of the components outperformed even those strict requirements.

“I can only attribute that to the fact that every guy in the project, every guy at the bench building something, every assembler, every inspector, every guy that’s setting up the tests, cranking the torque wrench, and so on, is saying, man or woman, ‘If anything goes wrong here, it’s not going to be my fault, because my part is going to be better than I have to make it.’ And when you have hundreds of thousands of people all doing their job a little better than they have to, you get an improvement in performance. And that’s the only reason we could have pulled this whole thing off,” Armstrong said.

“People just worked, and they worked until whatever their job was done, and if they had to be there until five o’clock or seven o’clock or nine-thirty or whatever it was, they were just there. They did it, and then they went home. So, four o’clock or four-thirty, whenever the bell rings, you didn’t see anybody leaving. Everybody was still working,” he said.

As Eagle neared the landing site, Armstrong found it to be a crater, with a steep slope and boulders the size of small cars strewn through the area. He famously skimmed the surface of the Moon, searching for a more advantageous site to land as Mission Control counted down the fuel remaining.

“We could have tried to land there, and we might have gotten away with it,” Armstrong recalled. “It was a fairly steep slope and it was covered with very big rocks, and it just wasn’t a good place to go. You know, if I’d run out of fuel, why, I would have put down right there, but if I had any choice of a more promising spot, I was going to take it.”

As Armstrong guided Eagle about a half mile ahead to a more level, less rocky site, he knew that if his speed and altitude were stabilized, he could free fall perhaps as much as 40 ft in the low lunar gravity, he told Ambrose and Brinkley.

“So, I was perhaps probably less concerned about [running out of fuel] than a lot of people watching down here on Earth. That’s not to say I wasn’t thinking about it, though, because I certainly was, but I thought it was important to try to get it down smoothly on the first try.”

And so, 50 years ago this month, on July 20, 1969 at 20:17:40 UTC, Armstrong and Aldrin became the first two humans on the Moon, a towering science and engineering achievement for the United States, effectively ending the space race.

“I was absolutely dumbfounded when I shut the rocket engine off and the particles that were going out radially from the bottom of the engine fell all the way out over the horizon, and when I shut the engine off, they just raced out over the horizon and instantaneously disappeared, you know, just like it had been shut off for a week. That was remarkable. I’d never seen that. I’d never seen anything like that. And logic says, yes, that’s the way it ought to be there, but I hadn’t thought about it and I was surprised,” Armstrong said.

As Armstrong and Aldrin walked on the Moon later—a part of the mission Armstrong gave a difficulty rating of one—Command Module Pilot Michael Collins waited above. In the decades following, he would be asked “millions of times” how frustrated he was to come so close to the Moon, but not step foot on it.

“I feel fine about it. I don’t have any little hidden agenda or hidden feelings about Apollo 11. I honestly felt really privileged to be on Apollo 11, to have one of those three seats. I mean, there were guys in the astronaut office who would have cut my throat ear to ear to have one of those three seats. … Did I have the best of the three? No. But was I pleased with the one I had? Yes!” Collins recalled in an oral history.

View a collection of photographs of the Apollo 11 mission

in our Flickr album NASA Lands on the Moon.