This timed exposure taken on March 5, 1981, shows the preparation work at Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Pad A, Complex 39, to prepare Columbia for the first launch of the space shuttle program, STS-1.

Credit: NASA

A veteran astronaut and a rookie team up on a test pilot’s dream.

Early on the morning of April 12, 1981, Commander John W. Young was strapped into the space shuttle Columbia, prepared again for its first launch. An attempt on April 10 was scrubbed because of an issue with the backup computer. In Young’s 19 years as a NASA astronaut, he had flown alongside Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom on Gemini 3, commanded Gemini 10, was the Command Module Pilot for Apollo 10, and landed the Lunar Module on the surface of the Moon as the Commander of Apollo 16. Today he would add “fly revolutionary new spacecraft” to that long list of accomplishments.

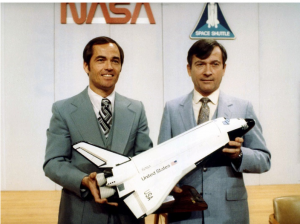

Crippen, left, and Young pose for photographers with a model of Space Shuttle Columbia following a press conference.

Credit: NASA

Beside Young, preparing for his first spaceflight—one that he considered a “test pilot’s dream”—was Robert L. Crippen, like Young, an accomplished naval aviator before joining the astronaut corps in 1969. Crippen, who began studying computer programing in 1959, was now an expert in the shuttle’s many computer systems.

“It was a real honor to get picked to go on that first one,” Crippen recalled at a KSC event marking the 25th anniversary of the flight. “John and I both were test pilot trained and when you look at the space shuttle, it was test pilot’s dream.”

“First, it had never flown in space in an unmanned fashion, which is the way we had always previously done our launch vehicles. First time we used big solid rockets. First time we had a winged vehicle that was going to come back in and land at a runway. And a number of other firsts. So, I couldn’t have picked a better flight to go on. And if you’re a rookie and you’re going on something like that, you want to go with an old pro. So, I was very fortunate to have an opportunity to go fly with John.”

Columbia arrived at KSC from California on March 24, 1979. It was shipped with about 8,000 of its 31,000 reusable lightweight thermal tiles not installed, and more were lost during the flight to Florida on the back of a specially modified 747 jet. Readying Columbia for the tremendous stresses of launch and reentry during the maiden flight presented the team at KSC with a formidable challenge.

The trip to KSC had raised questions about how the ceramic-coated silica tiles were bonded to the shuttle. NASA tested all the tiles in crucial locations, which was virtually all of them, by pulling on them with a special device. Eventually most of the tiles were removed, some strengthened, and then bonded to the shuttle with improved methods.

Waiting at Launch Complex 39A that morning, Crippen expected another launch delay coming out of a hold at T-9 minutes, when he started Columbia’s Auxiliary Power Units and more systems came online, he recalled in an oral history. However, the countdown continued smoothly. The weather, predicted to be an issue two days before, was good.

“About one minute to go, I turned to John. I said, ‘I think we might really do it,’ and about that time, my heart rate started to go up. I think they said it was—because we were being recorded— …up to about 130. John’s was down about 90. He said he was just too old for his to go any faster,” Crippen recalled with a laugh.

The long, productive space shuttle era began with a launch at 3 seconds past 7 a.m., April 12, 1981, 40 years ago this month. The raucous, 8.5-minute ride into Low Earth Orbit was propelled by more than 6.6 million pounds of thrust from the thunderous combination of Columbia’s three main engines and a pair of solid rocket boosters. Observers on the ground would never forget the aural and physical sensations of the 180-decibel launch.

Young and Crippen spent two days in space. With the only payload aboard being a device to monitor Columbia’s performance and flight data, the two astronauts spent their time working through nominal flight procedures for the new spacecraft. They tested the main engines, the orbital maneuvering engines, the payload bay doors, the inertial measuring units, the star trackers, the environmental control system, the Freon loops, and more. By the end of the flight, they had accomplished all 113 objectives.

“We prepared for so many disaster scripts and simulations where everything went wrong. And so little went wrong, in terms of start to finish, that that is probably the most memorable thing,” Young explained in an interview with JSC’s Space News Roundup in 1991. “The whole mission was just like we planned it. We didn’t run into anything we didn’t expect. We did lose some tiles on the OMS pod, but that was about all we could see on board.”

On April 14, 1981, Columbia was still traveling 8 times the speed of sound, at an altitude of 151,000 feet when Crippen first saw the U.S. West Coast. “What a way to come to California,” he said to Joseph P. Allen, entry CAPCOM. Young brought Columbia in for a landing, touching down in the early afternoon on Runway 23 at Edwards Airforce Base, returning from space in a way no other spacecraft had ever done.

“Don’t ask me why I knew reentry would work. I just had a feeling when we started reentering that it was going to go great,” Young said. “But, the shuttle was working so well, I wanted to stay up there another two or three days and see how it really worked.” Young, thrilled by the shuttle’s performance, walked the length of Columbia several times after landing, examining the spacecraft and excitedly pumping his fists.

With STS-1, Young became the only astronaut to fly four different types of spacecraft, a record he holds to this day. Already the chief of the Astronaut Office during STS-1, he continued in that position and went on to command STS-9. Crippen went on to Command STS-7, STS-41-C, and STS-41-G.

Visit APPEL KS’s Shuttle Era Resources Page to learn more about STS-1 and the 134 shuttle missions that followed over the next 30 years, missions that deployed key satellites, repaired the Hubble Space Telescope, enabled important new research, and were instrumental in construction of the International Space Station. The Shuttle Era Resources Page also contains important resources on the Challenger and Columbia tragedies and enduring lessons learned.