Dr. Nancy Grace Roman records data from a computer display at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, circa 1972. In 1959, she became the first female executive and the first Chief of Astronomy at NASA.

Photo Credit: NASA

Nancy Grace Roman, NASA’s first chief of astronomy, blazes a trail for the Hubble Space Telescope decades before launch.

On warm summer nights in 1935, a music teacher named Georgia would step outside her family’s small house on the outskirts of Reno, Nevada. Here, away from the lights of the city, Georgia would look into the vast night sky, spread between the Sierra Nevada and the Carson Range. Walking through the empty lots surrounding them, the young mother would point out constellations to her 10-year-old daughter, Nancy. Reno was the seventh city the family had called home since Nancy was born in Nashville, Tennessee in 1925.

“There were no houses across from us, an empty lot behind us, a ranch on the other side of us, an empty lot on all three sides of us, I guess, plus the ranch. So, we had a really clear, dark sky. I wouldn’t be surprised if that had a major influence on my being interested in astronomy. I don’t know. As I said, I don’t really know when I started,” Dr. Nancy Grace Roman would recall, 65 years later, in an oral history.

“She really got me interested in looking at the sky,” Roman added.

Dr. Nancy Grace Roman is shown with a model of the Orbiting Solar Observatory (OSO) in 1962. She was the first Chief of Astronomy in the Office of Space Science at NASA Headquarters and the first woman to hold an executive position at NASA. In her role, she had oversight for the planning and development of programs including the Cosmic Background Explorer and the Hubble Space Telescope.

Photo Credit: NASA

Roman earned her doctorate in astronomy from the University of Chicago in 1949, doing research at the school’s Yerkes Observatory at Williams Bay in southeastern Wisconsin. She began a career in academia at a time when there were few women in STEM fields, publishing research that noted the emission spectrum she observed from the star AG Draconis was completely different than previous observations. This led to AG Draconis being designated as a variable star in 1964.

In March of 1959, 65 years ago this month, Roman was preparing to begin a job at NASA. Earlier that year, she attended a lecture at NASA Headquarters by Harold Urey, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934. A NASA official asked Roman, who was working in radio astronomy at the Naval Research Laboratory by then, if she knew anyone who would be interested in creating a space-based astronomy program at NASA.

“Well, I debated about it because I knew it would mean leaving research, and I had enjoyed research,” Roman recalled. “I also had had only one bit of experience in management, and that was not terribly successful. But I finally decided that the challenge of starting with a completely clean slate and mapping out a program that would influence astronomy for fifty years was just more than I could turn down.”

Roman became NASA’s first chief of astronomy. This made her the first woman to hold a leadership position at the fledgling space agency, which attracted a great deal of media attention at the time. One writer mentioned Roman’s Southern accent in an article that was syndicated across the country.

“All of the people in Washington were just very amused by the whole thing because I’d lived away from the South so long that I didn’t really have a trace of a Southern accent. It was pretty clear that the columnist had not actually talked to me,” Roman recalled.

The new position, she explained, was a “blank check.” She began with four astronomy satellite projects that had been identified earlier by the National Academy of Sciences as top priorities, following a comprehensive survey of scientists. These projects formed the basis of NASA’s early astronomy program.

Ready for transportation to the Kennedy Space Center, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is pictured onboard the strongback dolly at the Vertical Processing Facility (VPF) at the Lockheed assembly plant upon completion of final testing and verification.

Photo Credit: NASA

“I did an awful lot of traveling in my early years, trying to visit all of the major astronomy departments in the country. I also visited industry, but that was in a different role primarily. And talking, trying to get them interested in doing astronomy from space, whether from rockets or balloons or satellites, telling them what the possibilities and constraints were, finding out what they thought would be important. Then, on the basis of that, I tried to formulate the science program that would make sense and what sorts of facilities we needed to carry out that program,” Roman recalled.

One of the top priorities for astronomers was a large telescope, about 9 feet in diameter, that operated beyond the interference of Earth’s atmosphere. As early as 1962, the scientific community was studying the possibility of using the Apollo booster, just under development, to place such a significant telescope into space. Roman thought the discussions were interesting, but ahead of their time.

“I knew how much trouble we were having trying to build a satellite to carry a 6-inch telescope. The idea of getting started on a 9-foot telescope didn’t appeal to me,” Roman said. “But it did appeal to the aerospace companies, and it particularly appealed to a NASA center in southern Virginia (Langley Research Center). They had responsibility for the manned spaceflight program at that time. They thought this idea of a telescope above the atmosphere where a man could ride along looking through the telescope was just the greatest thing they could think of.”

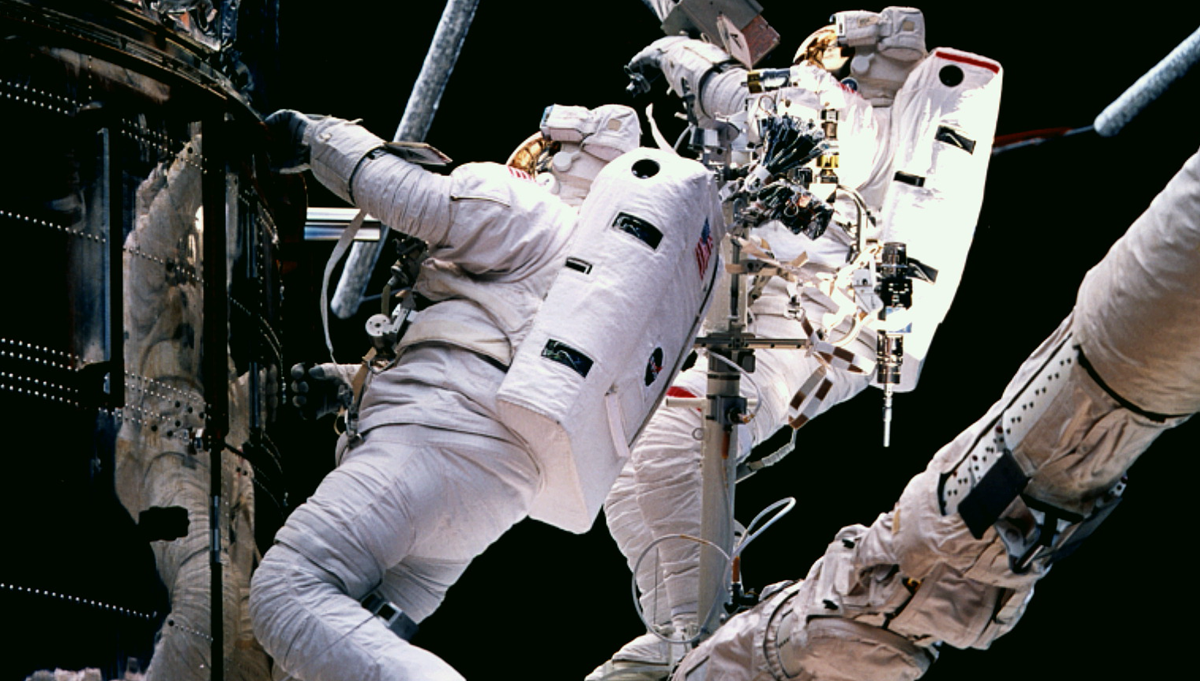

An astronaut riding aboard the telescope, Roman reasoned, would require an atmosphere, and no matter how still an astronaut tried to remain on orbit, any movements would inevitably invalidate crucial data.

“I still thought it was a little early to get started on a 9-foot telescope. But, okay, if they’re going to do it, we will do it. All I did was to bring together a collection of astronomers from all over the country and some NASA engineers, and get them to sit down together and come up with something that the engineers thought would work, and that the astronomers thought would do their job. That was really the beginning of the serious effort on the Hubble,” Roman said, in a NASA interview.

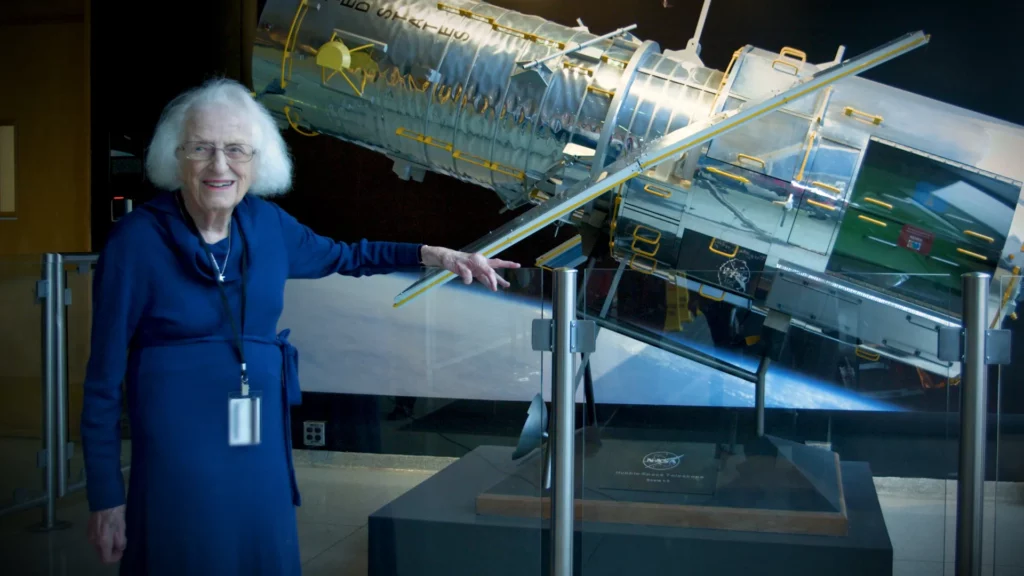

Dr. Nancy Grace Roman stands next to a scale model of the Hubble Space Telescope outside the Hubble control center at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Roman is known as the “Mother of Hubble.” Photo Credit: NASA

What the engineers thought would work and the astronomers thought would do their job became the Hubble Space Telescope. Roman tirelessly championed its development for decades. Although she retired from NASA in 1979 to care for her mother, Georgia, she later returned to work in the Astronomical Data Center at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, serving as its director from 1995 to 1997.

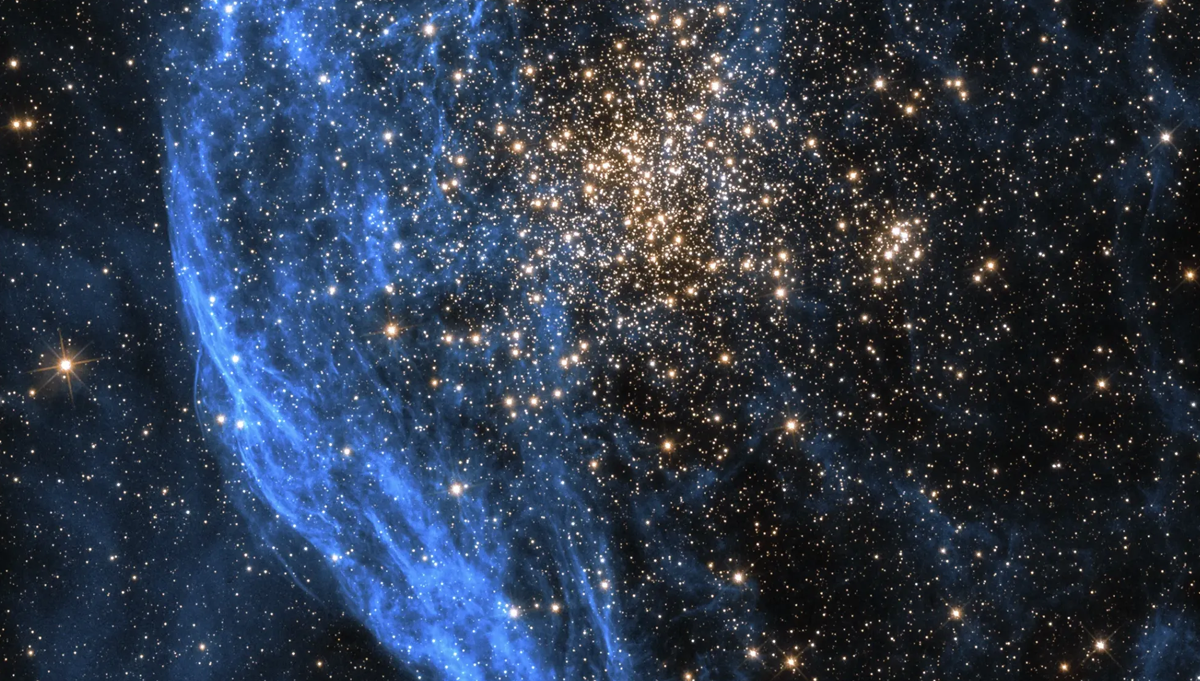

Hubble launched aboard Space Shuttle Discovery on April 24, 1990. In the nearly 34 years since, Hubble has rewritten human understanding of the Universe.

“I think it has more than lived up to the expectations,” Roman said. “I think we have done everything that we said we were going to do, and more.”

In 2020, NASA announced that an infrared space telescope under development would be named the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope To learn more about Dr. Nancy Grace Roman during Women’s History Month, click here and here.