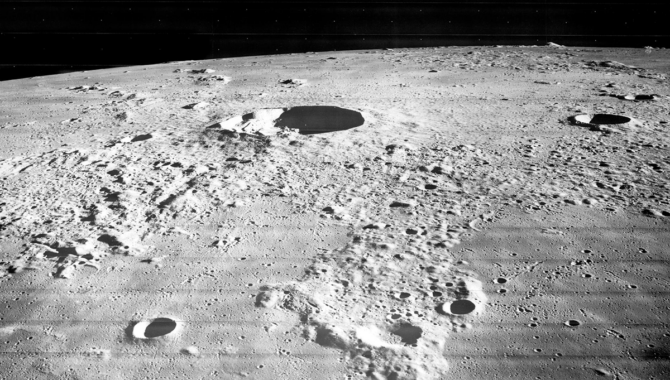

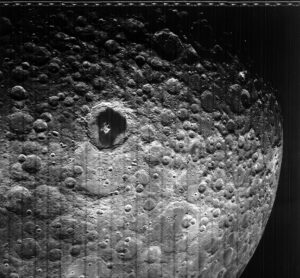

The surface of the Moon captured by Lunar Orbiter 3. The Lunar Orbiter program took more than 3,000 images of the Moon, which helped NASA program managers, scientists, and mission managers identify the landing sites for Apollo lunar landings. Credit: NASA

A young geologist catalogs thousands of photos of the lunar surface and helps to identify key landing zones for the Apollo program.

In 1967, a curious young geologist walked into the library at NASA headquarters to find the nine empty tables he’d asked the librarian for on the day before, and more than 2,000 black and white photos of the lunar surface. After spreading clean white sheets over the tables, he began dusting and sorting photos from NASA’s Lunar Orbiter missions.

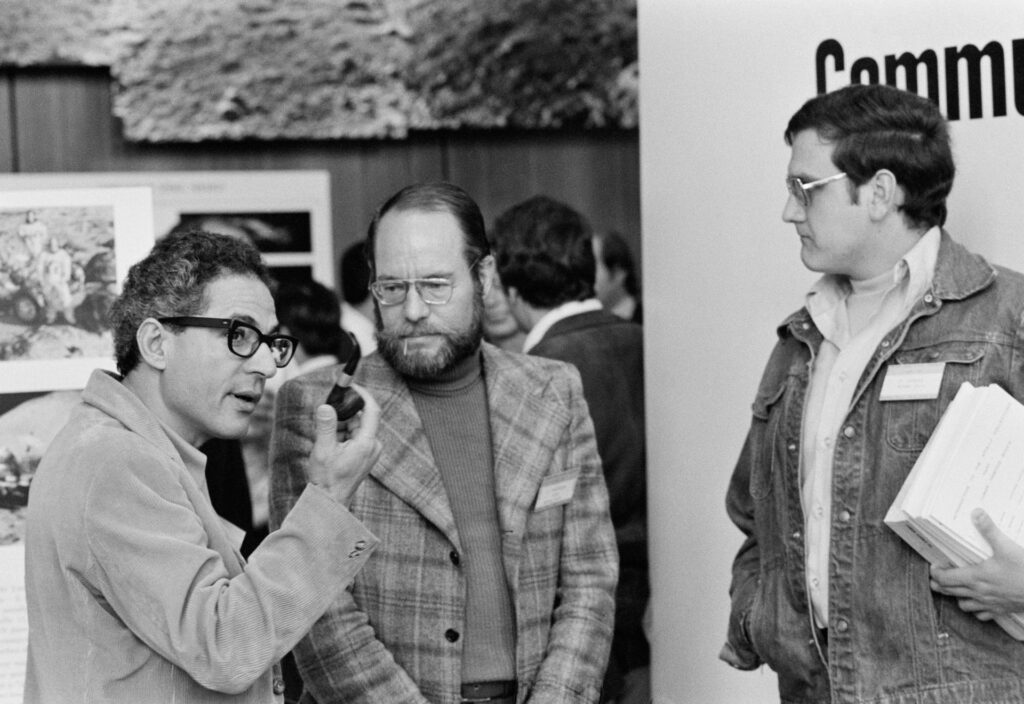

Apollo 17 Command Module Pilot Ronald E. Evans, center, recieves lunar orbital geology instruction from geologist Farouk El-Baz, right, as support astronaut Robert F. Overmyer looks on. Credit: NASA

The geologist, Farouk El-Baz, had been warned that the position he had accepted earlier that year summarizing reports for a NASA contractor was a “lousy … paper shuffling job.” But when his coworkers gave him reams of photos of the lunar surface, he was fascinated. And now, at the library, he faced a new stack of images.

“It took me three days to organize all the pictures that had been collected by Lunar Orbiter then and put them in stacks by the mission and by the numbers and all like that,” said El-Baz, in an oral history.

At the time, geologists working with NASA were regularly meeting at Langley Research Center, presenting information about features at certain sites on the lunar surface. At one of the meetings, El-Baz said he realized that although the reports highlighted details about these important geological features, they didn’t connect to the larger context.

“I would go to that room, sit down, take all the pictures one by one, see what’s in it, take one three-by-five card, we didn’t have computers…,” El-Baz recalled. “I’d write the mission number, the frame number, and then write some notes on what that picture contained, what features, one by one. Went through them all, couple thousand of them, and organized them.”

Looking over the images, he asked himself a simple question: why does NASA need geologists? And he arrived at a simple answer: to select landing sites on the Moon.

“I took my list, the card file, one by one, went through them all—this is here, this is here, this one here. I came up at the very end with a list of 16 places on the Moon. If we [went] to all these places, we would see every single type of lunar surface feature and therefore we would have sampled every kind of lunar rock, if these features have different types of materials or rocks,” El-Baz recalled.

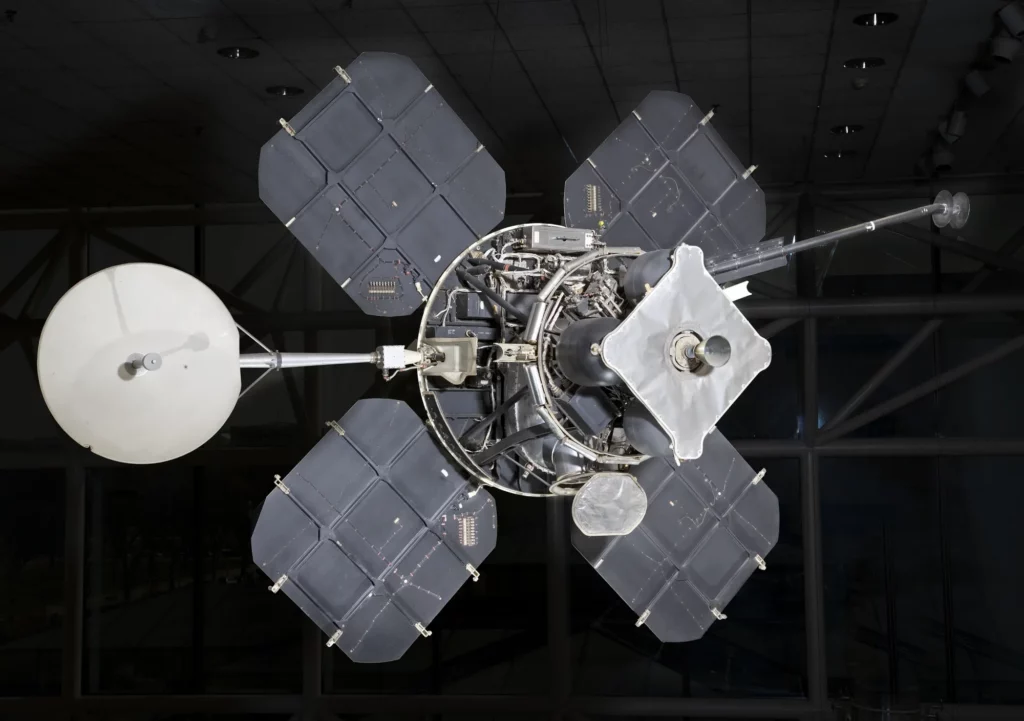

NASA had approved the Lunar Orbiter program on August 30, 1963, 61 years ago this month. Lunar Orbiter 1 launched on August 10, 1966, atop an Atlas-Agena D rocket. Four days later it became the first U.S. spacecraft to orbit the Moon, establishing an elliptical trajectory of 118-miles by 1,160-miles. The spacecraft weighed 850 pounds and was equipped with four solar panels and a sophisticated imaging system that used two lenses simultaneously to capture both high-resolution and medium-resolution photographs at the same time. The system developed the film in space, scanned the images, and transmitted them to Earth via a 36-inch diameter dish antenna.

Lunar Orbiter 1 had taken 205 images of the lunar surface by August 28, 1966, including all the potential landing sites NASA had identified at that time for Apollo and important sites on the far side of the Moon. It took until September 16 to transmit the images to Earth. In late October, with the spacecraft running low on fuel, NASA crashed it into the far side of the Moon.

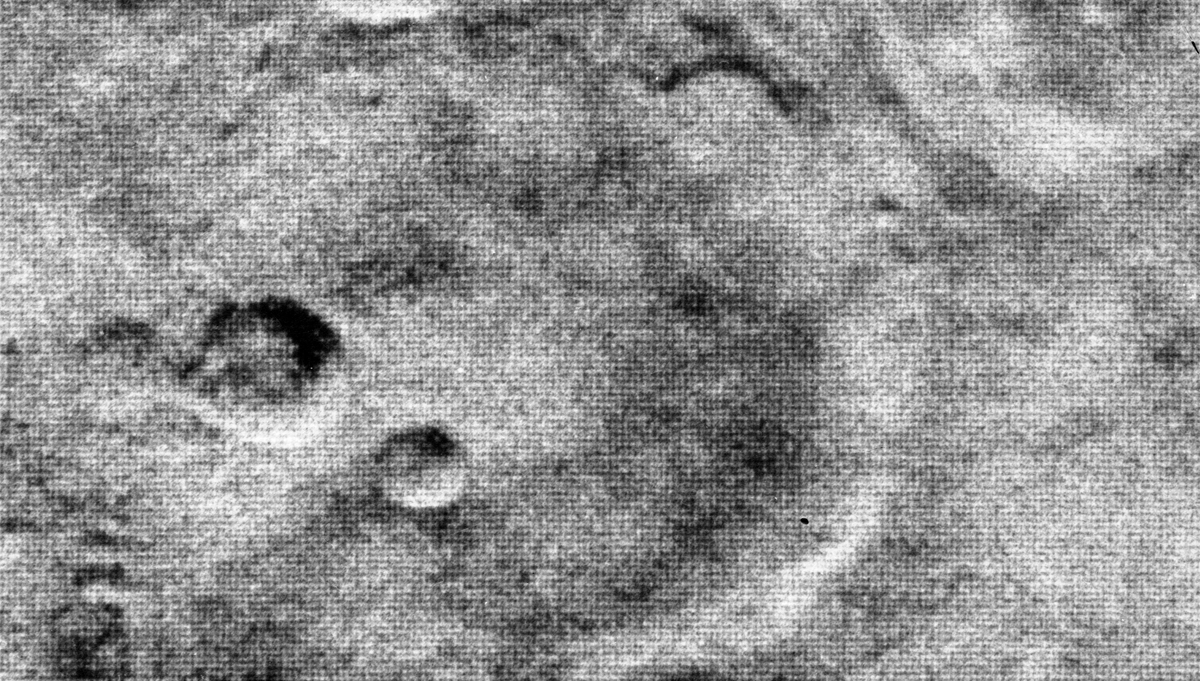

This photograph of the hidden or far side of the Moon was taken by Lunar Orbiter III during its mission to photograph potential lunar-landing sites for Apollo missions.

Credit: NASA

Between November 6, 1966, and August 1, 1967, NASA launched four more Lunar Orbiter spacecraft. Each orbited the Moon and successfully photographed the lunar surface. Lunar Orbiter 2 orbited for nearly a year, photographing 13 primary and 17 secondary potential landing sites near the equator.

During just two months in 1967, Lunar Orbiter 4 took 163 photographs that represented 99 percent of the near side of the Moon and 75 percent of the far side. Lunar Orbiter 5 photographed most of the far side of the Moon and 36 key areas on the near side, as well as gathering information to help NASA more precisely define anomalies in the lunar gravitational field.

The five Lunar Orbiter spaceflights produced 3,062 photographs of the lunar surface that NASA scientists, program managers, and mission planners used to look for relatively flat, unobstructed landing sites near the Moon’s equator and to identify key features to explore and collect samples from.

In 1967, after El-Baz had compiled his detailed card file of the Lunar Orbiter images, he called the organizer of the geological meetings and asked for an hour to present his findings to the group.

“What are you going to talk about?” the man asked.

“About 16 sites on the lunar surface.”

“ ‘Give me an example.’ So, I gave him one. ‘Give me another example.’ I gave him another one by telling him where we would go and what we would find. So, he said, ‘How about that? Another example?’ So, I gave him a third example. He said, ‘Well, that’s interesting. I’ll put you on the program,’ ” El-Baz recalled.

Dr. Farouk El-Baz (left) chats with other participants of the Eighth Annual Lunar Science Conference.

Credit: NASA

“Most of the Apollo sites that we visited really fall within the same range of the 16 sites, not necessarily exactly the place, but within the range,” El-Baz said. “I became part of the geology group and slowly but surely, I became the spokesman of geology at NASA Headquarters and with the NASA engineers in Houston. Wherever it was, I became the guy that speaks on behalf of the geology community.”

El-Baz was in Mission Control on July 20,1969 when Apollo 11 landed on the Moon.

El-Baz worked closely with the Apollo astronauts, finding they learned geology quickly when fueled by competition. He helped them understand the landing sites they were heading to on the mission, what to look for on the lunar surface, and some terminology to use in describing it.

Over the course of six successful lunar landings, the world watched as the black and white photographs from the Lunar Orbiter program came to life in full color photos, television images, astronaut descriptions, and the 842 pounds of lunar rocks, core samples, and regolith the astronauts brought to Earth.

To learn more about the Lunar Orbiter program, click here. To learn more about the Apollo program that landed humans on the Moon, see APPEL KS’s Apollo Era Resources page.