A Mercury capsule is mounted inside the Altitude Wind Tunnel for a test of its escape tower rockets at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Lewis Research Center. Credit: NASA

Maxime Faget built on groundbreaking work by H. Julian Allen to shape the future of NASA space exploration.

On August 11, 1958, a team of engineers at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) published a research memorandum that would echo down through the next decade, as the United States and the Soviet Union raced to put the first human on the Moon.

The team was led by Maxime Faget, a talented mechanical engineer who had served in the U.S. Navy aboard a submarine during World War II. In 1946, Faget joined NACA, working as a research scientist at what is now NASA’s Langley Research Center. He was assigned to help develop an airplane that would fly higher and faster than ever before—a project that became NASA’s X-15. As that plane progressed through development, talks began about a new airplane that would push the envelope even further.

A 1/10th Scale Model of the X-15 research plane is prepared in Langley’s 7 x 10 Foot Wind Tunnel for studies relating to spin characteristics. Credit: NACA/NASA

“The first set of X airplanes got us up to Mach 3 and then the X-15 got us up to six, so the third round would get us to something faster, and more or less the minimum objective was to go at least twice as fast as the X-15,” Faget recalled, in an oral history.

Researchers from Langley, Ames Research Laboratory, and other NACA Laboratories were set to gather in mid-October 1957 to discuss their ideas. But on October 4, the agenda changed.

“A couple of weeks before that meeting, the Russians put up their Sputnik. Of course, that set us all back, you know,” Faget recalled with a laugh. The engineers began to shift their focus from a faster airplane to rockets. “We talked about rocketing men up into orbital velocity and how to get them back and so forth.”

Faget went home and worked with colleagues Benjamin J. Garland and James J. Buglia to build upon the research of influential aeronautical engineer H. Julian Allen, who published a landmark paper in 1953 presenting what is known as “the blunt body theory.”

The theory asserts that a blunt, rounded object creates a shockwave as it enters Earth’s atmosphere at high speed. This shockwave deflects some of the intense heat caused by atmospheric friction and moves it away from the object. It also provides a greater degree of control during reentry and increases the object’s rate of deceleration.

“Both the Army and Air Force were having trouble bringing their missile warheads down to ground zero, and [Allen] just simply said, ‘Well, if you make the drag a little higher, you’ll get down there. You won’t get down as fast, but you’ll get down there without burning up.’ I won’t go into all the reasons for this, but what he’d done made an awful lot of sense to me,” Faget said.

As the world stood at the doorway to the space race, it was surprisingly unclear what form a crewed spacecraft might take. Faget’s team, arrived at the idea of a capsule that was shaped to capitalize on the advantages of blunt body reentry. “A weight of 2,000 pounds was chosen as being reasonable for the ballistic reentry satellite. A diameter of 7 feet was chosen as being adequate for the occupant supported in the prone or supine position,” the team wrote in the memorandum, Preliminary Studies of Manned Satellites; Wingless Configuration: Nonlifting.

“In a matter of, oh, I guess three or four weeks, we came up with a pretty good idea of what to do. It was a pretty neat paper. We did a pretty good job of scanning all the possibilities of that thing,” Faget recalled.

In the summer of 1958, as NACA was preparing to be absorbed into the newly created NASA, Faget was among a group of engineers who met with U.S. military officials and learned about the fledgling space efforts of the U.S. Department of Defense, including rocket programs.

“I’ll tell you, it became immediately apparent to me that the only practical approach was the one I had proposed, simply because it provided the lightest way to do it, and we were very, very short of big launch vehicles. We had very cleverly designed a much lighter atomic device—that’s what they liked to call them… So, we didn’t have to develop big heavy rockets. So, we didn’t have much rocket power,” Faget said.

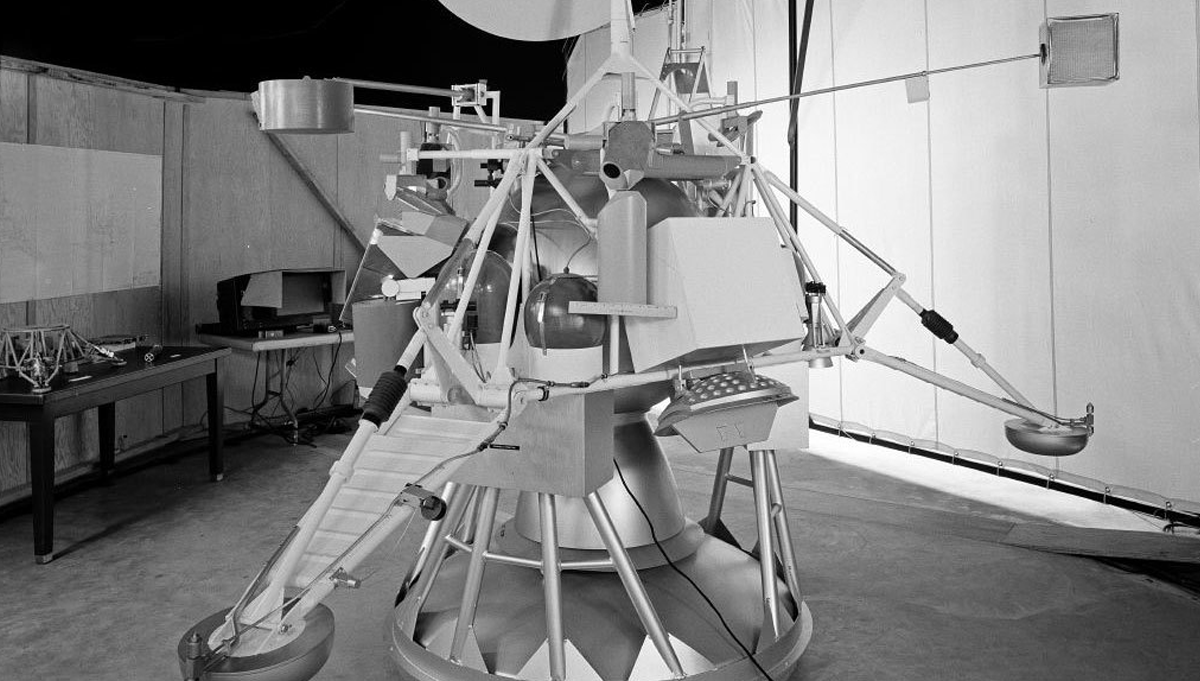

The Mercury capsule that carried the first NASA astronauts into space and back was cone-shaped, with room for one-human. It was 6 ft, 10 in. high and 6 ft, 2 1/2 in. in diameter, very close to what Faget and his colleagues had envisioned in the winter of 1957. It was fitted with a 19-foot-tall escape rocket that could rapidly pull the capsule to safety during a launch mishap.

“Bob Gilruth [Director of NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center] came in one day and says, ‘Max,’ he says, ‘what are you going to do if the Atlas blows up on the way up?’ And I didn’t have an answer for that. And he said, ‘Well, you’d better get an answer for it,’ ” Faget recalled. The answer Faget engineered was a single-motor, solid-fueled rocket with three nozzles mounted atop a tower.

“The escape rocket with the capsule on it would leave at eighteen Gs. It really was a thing. But the escape rocket all by itself would leave around forty Gs, maybe forty-five Gs, about three times as fast,” Faget recalled with a laugh.

On March 24, 1961—64 years ago this month—NASA launched Mercury-Redstone BD, the final uncrewed test of the Redstone rocket. Engineers needed to ensure they had resolved vibration and acceleration issues observed in earlier test flights before committing to a crewed mission. Their success paved the way for Alan Shepard’s historic flight on May 5, 1961, making him the first American in space. He rode into space aboard the lightweight Mercury capsule engineered by Maxime Faget using Allen’s blunt body theory. The capsule design would become the foundation of the U.S. space program for the next decade.

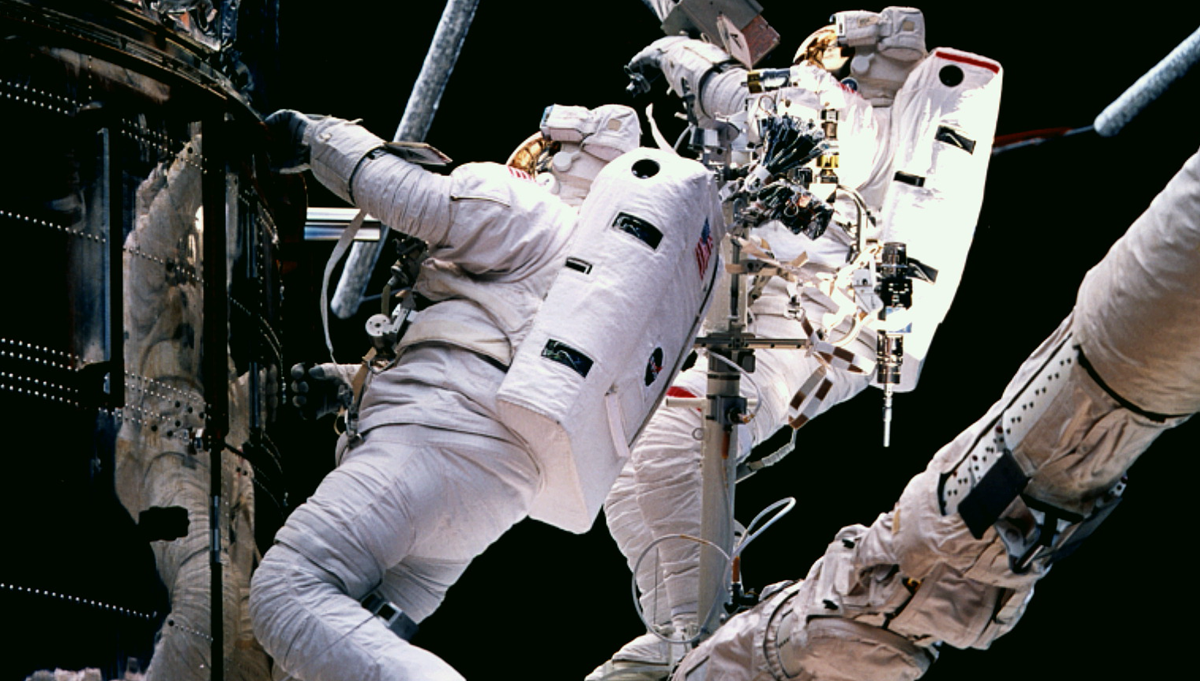

In 1962, Faget was appointed Director of Engineering and Development at NASA’s newly established Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas, where he tackled the engineering challenges of the Gemini and Apollo programs. Later, he played a key role in planning the Space Shuttle, including offering wing configurations and advocating for a continuous improvement process that would have resulted in new versions of the Shuttle during the program. He retired from NASA in 1981.

“He was a true icon of the space program. There is no one in spaceflight history, in this or any other country, who has had a larger impact on man’s quest in space exploration,” said Christopher Kraft, who was the flight director for all six crewed Mercury missions.

To learn more about Project Mercury, Project Gemini, and Apollo, visit the APPEL Knowledge Services Knowledge Inventory.