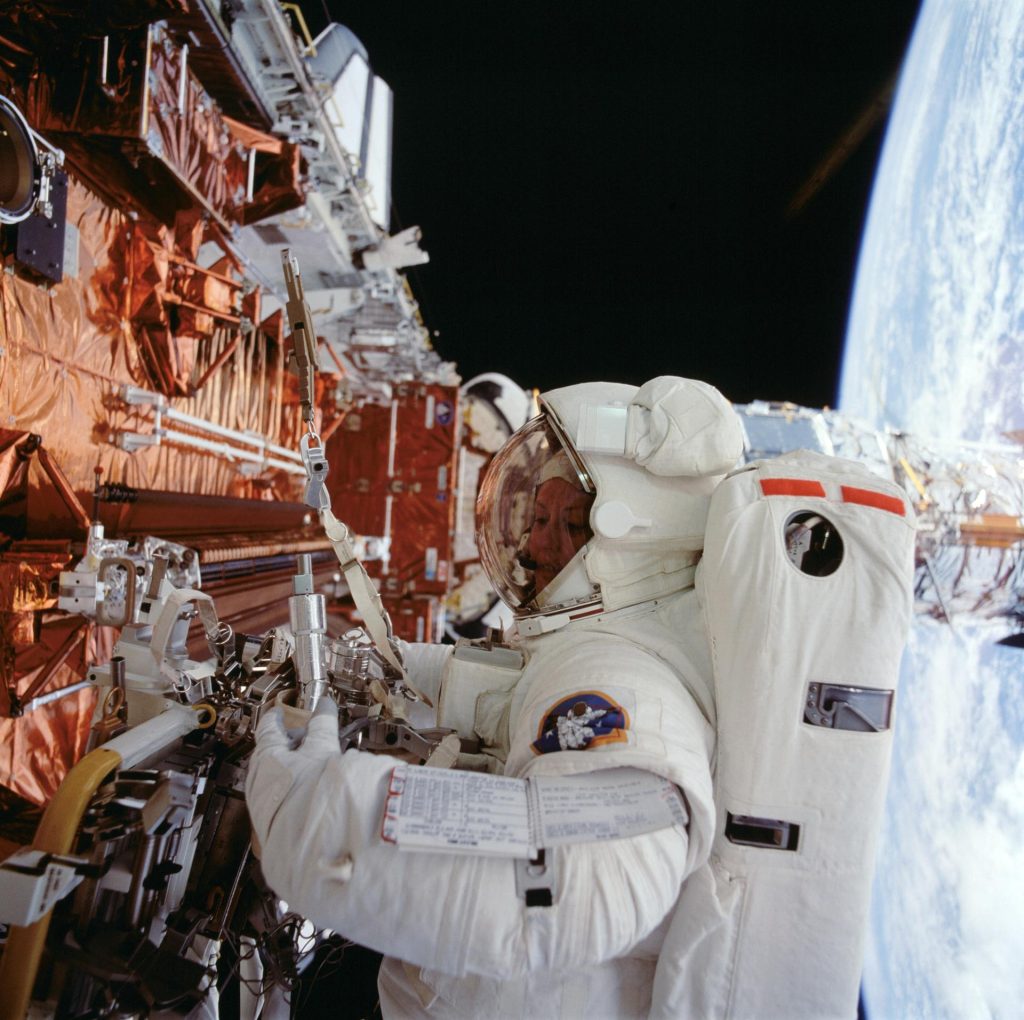

Astronaut F. Story Musgrave, anchored on the end of the Remote Manipulator System (RMS) arm, prepares to be elevated to the top of the towering Hubble Space Telescope (HST) to install protective covers on magnetometers. Astronaut Jeffrey A. Hoffman (bottom of frame) assisted Musgrave with final servicing tasks on the telescope, wrapping up five days of extravehicular activities (EVA).

Credit: NASA

Ambitious mission includes five EVAs, unprecedented rendezvous.

When NASA astronaut Richard O. Covey saw the Hubble Space Telescope in early December 1993, it was a spectacular sight, its silver insulation and gold solar arrays gleaming “as bright as anything you can imagine,” casting them in stark relief against the blackness of space.

As Commander of shuttle mission STS-61, Covey was piloting the Space Shuttle Endeavour to a rendezvous with Hubble, then the largest object a shuttle had approached in space. It was Covey’s fourth spaceflight, but the first with a seven-person crew. It was Payload Commander F. Story Musgrave’s fifth spaceflight, and Mission Specialist Jeffrey A. Hoffman’s fourth. Pilot Kenneth D. Bowersox and Mission Specialists Kathryn C. Thornton, Claude Nicollier, and Tom Akers were also experienced astronauts.

With the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) berthed in Endeavour’s cargo bay, crew members for the STS-61 mission pause for a crew portrait on the flight deck. Left to right are F. Story Musgrave, Richard O. Covey, Claude Nicollier, Jeffrey A. Hoffman, Kenneth D. Bowersox, Kathryn C. Thornton and Thomas D. Akers.

Credit: NASA

“One thing about having seven people is that when you’re doing a rendezvous, you get an awful lot of help. A lot of people taking pictures and trying to look out the windows and see what’s there and stuff, but that was okay,” Covey recalled with a laugh. “The rendezvous went very much like we expected it to.” And then ESA astronaut Nicollier used Endeavour’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS) to capture Hubble—43.5 feet long and 14 feet in diameter.

“You look at this big telescope out there, and it’s just floating motionless above the payload bay, and yet we’re both moving at 18,000 miles an hour, five miles a second. I’m a physicist; I understand it intellectually, but it still is pretty awesome when you see it,” Hoffman recalled, in an oral history. “That’s when Covey radioed down, ‘We have a handshake with Mr. Hubble’s telescope.’ Everybody cheered. The first phase of the mission had gone successfully.” Nicollier secured Hubble upright in the payload bay.

And so began what still stands as one of the most ambitious, challenging, and complex human space missions in history—the first servicing mission of the Hubble Space Telescope—29 years ago, this month. The spaceflight included five extravehicular activities (EVAs) in which four astronauts, working in two teams, spent a combined 35 hours and 28 minutes outside the shuttle performing an extensive list of repairs and enhancements to Hubble.

Among the crew, Musgrave and Hoffman were known as the “odd couple” because they were assigned EVAs one, three, and five. Akers and Thornton, assigned EVAs two and four, were known as the “even couple.”

“We’ve got the telescope; now [we’ve] got to go fix it. …That night Story and I got our spacesuits ready. All four of us worked together on this, because when you get a spacesuit ready you try to be each other’s personal valet. …There’s just a lot of work to be done. When you’re doing a spacewalk, it really takes over the entire Shuttle,” Hoffman said.

Shuttle mission STS-61 still stands as one of the most ambitious, challenging, and complex human space missions in history—the first servicing mission of the Hubble Space Telescope—29 years ago, this month.

Credit: NASA

The mission had grown in complexity after the veteran crew was assigned, Covey recalled in an oral history. What had begun as a three-EVA mission, grew to five EVAs, with an unprecedented rendezvous, and large lifts with the RMS. It “really pushed the bounds of what people thought we could do,” Covey explained. These elements combined to make STS-61 an incredibly appealing mission to astronauts who discouraged calls to separate the repairs into two missions.

“We thought we had enough time, if things worked,” Hoffman said. “We had enough time to accomplish everything. It was nonstop, there’s no question, the training. That’s just part of the job, but I didn’t feel under a high stress… I work hard, and then I go home at night and leave it.”

Over three EVAs, Musgrave and Hoffman spent approximately 22 hours in the shuttle’s open payload, bay replacing two Rate Sensing Units (RSUs) that employ gyroscopes to help maintain stability as the telescope is pointed, exchanging eight electrical fuse plugs, substituting Hubble’s Wide Field/Planetary Camera (WF/PC), for an upgraded spare unit that was modified to compensate for the flaw in Hubble’s primary mirror, and replacing the Solar Array Drive Electronics unit.

“…For me it was the first time that I would ever have done multiple EVAs,” Hoffman recalled in an oral history. “We spent a lot of time working on those procedures. It turns out to be rather complicated and time-consuming because you don’t just get your spacesuits out, use them, and then put them away. After each EVA, you have to clean them; you have to change out the lithium hydroxide carbon dioxide scrubbers. You have to make sure that the batteries are charged, which means that some batteries are being charged and other batteries have to get put in the suits. You have to keep a record of everything.”

Over two EVAs totaling 13 hours and 25 minutes, Akers and Thornton installed new solar arrays, removed Hubble’s High-Speed Photometer and substituted it with the Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement unit, which compensated for the flaw in the primary mirror, and installed a co-processor that added memory to and increased the speed of Hubble’s computer.

The EVA teams skipped the “post sleep” period scheduled in the morning, immediately preparing for their EVAs after their alarm sounded. This provided them with a margin to extend an EVA if it were required. “Each day the crews just got better and better at it, so it was a real steep learning curve. By the time Story and Jeff got around to their third EVA of the mission, they’d wake up, do their stuff, and man, they’d be ready to go. I’m sitting there still brushing my teeth, saying, ‘What do you mean you’re going outside?’” Covey recalled with a laugh.

Astronaut Kathryn C. Thornton works with equipment associated with servicing chores on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) during the fourth extravehicular activity (EVA) on the eleven-day mission.

Credit: NASA

Endeavor returned to Kennedy Space Center on December 13, 1993. The Hubble team had to wait weeks for the newly installed instruments to acclimate to the cold vacuum of space before turning on the high voltage electronics.

“I’ll never forget. It was the wee hours of January 1st. We had had people over for a party. Everybody had left. I think I was up alone in the kitchen; I was just cleaning up,” Hoffman said. “The phone rang. It was an astronomer friend of mine from the Space Telescope Science Institute. He said, ‘Jeff, Hi. Do you have any champagne left?’

“I said, ‘Yes, I still have a half bottle in the refrigerator.’

“He said, ‘Well, crack it open, because we’ve just gotten the first pictures back from Hubble, and it works.’”

The repairs designed by teams at NASA and made by the crew of STS-61 in space fully corrected the fuzzy halo effect seen in early Hubble images, enabling the space telescope to examine distant points in the universe as it was designed to, with staggering clarity and sensitivity. NASA demonstrated how successful the repairs had been on January 13, 1994, with the release of a sharp image of galaxy M100’s core, which is 30 light-years across and 56 million light-years from Earth. Hubble has now made more than 1.5 million observations and become synonymous with awe-inspiring images of space.

Visit APPEL KS’s Shuttle Era Resources Page to learn more about STS-61 and the 134 other shuttle missions that deployed key satellites, enabled important new research, and were instrumental in construction of the International Space Station.