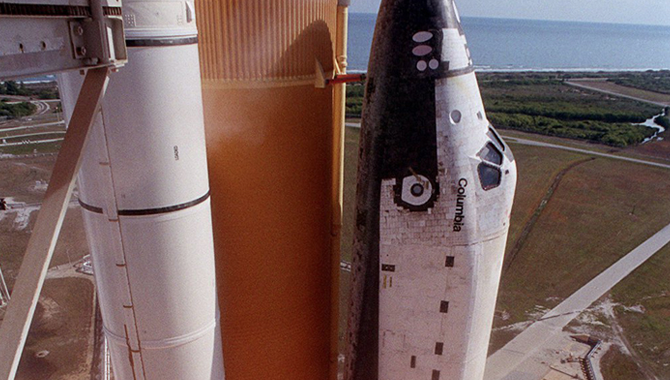

Through a cloud-washed blue sky above Launch Pad 39A, Space Shuttle Columbia hurtles toward space on mission STS-107. Following the countdown, liftoff occurred on-time at 10:39 EST. Experiments in the SPACEHAB module ranged from material sciences to life sciences. Photo Credit: NASA

Vol. 6, Issue 1

The loss of the crew of STS-107 aboard Space Shuttle Columbia on February 1, 2003 marked a turning point for NASA.

Through a cloud-washed blue sky above Launch Pad 39A, Space Shuttle Columbia hurtles toward space on mission STS-107. Following the countdown, liftoff occurred on-time at 10:39 EST. Experiments in the SPACEHAB module ranged from material sciences to life sciences.

Photo Credit: NASA

It is hard to fathom that it has been ten years. My feelings about the immensity of that loss have not receded. Yet when I stop and think about NASA then and now, it is clear that time has passed.

After the Columbia accident, the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB) wrote that, “NASA’s current organization…has not demonstrated the characteristics of a learning organization.” What the CAIB meant was the NASA did not know how to use what it knew. This underlying problem demanded more than a new system for sharing lessons learned or best practices. It also required an open culture in which people could speak openly about what they knew without fear of retribution.

NASA responded in a number of ways. There were new checks and balances, such as the establishment of a chain of technical authority and a process for ensuring that dissenting opinions could be voiced. The agency also changed its governance model, and as a result difficult go/no-go decisions such as the launches of STS-121 and the New Horizons mission to Pluto took place at the highest levels, with extensive input from the programmatic, engineering, and safety and mission assurance communities. Differences of opinion were aired and documented.

NASA is a different organization today than it was in 2003, particularly where knowledge and learning are concerned. When tough programmatic decisions arise, leaders such as Chief Engineer Mike Ryschkewitsch encourage capturing those stories as case studies or articles that include rich context and quotes from multiple practitioners with divergent views. Painstaking efforts have been made to document the closeout of programs such as the Shuttle and Constellation. Every center and mission directorate has either a Chief Knowledge Officer or a point of contact to serve as the advocate for the knowledge needs of the organization’s practitioners. Cross-agency support organizations such as the NASA Safety Center (NSC) and the NASA Engineering and Safety Center (NESC) foster knowledge exchanges that connect practitioners throughout the agency. These interwoven threads are helping to create a resilient knowledge organization.

We are not there yet. Knowledge is not universally accessible across organizational lines. Half the NASA workforce is eligible for retirement, and could walk out the door with critical knowledge. Young professionals at the other end of the career path have had fewer opportunities than previous generations at NASA to get hands-on experience. There is plenty left to do. But it has been a decade of real progress.

We owe it to the crew of STS-107—Rick Husband, Willie McCool, Michael Anderson, David Brown, Kalpana Chawla, Laurel Clark, and Ilan Ramon—to be better and do better, because we knew them.