Gemini XII astronaut James A. Lovell, Jr. (left), command pilot, and Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr. (right), pilot, eat a piece of cake presented to the two astronauts by crew members of the prime recovery ship, USS Wasp. Gemini XII splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean at 2:21 p.m. (EST), Nov. 15, 1966, to conclude a four-day mission in space.

Photo Credit: NASA

Aldrin pioneers under water training for EVAs.

In the fall of 1966, James A. Lovell, Jr., and Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr. visited the sprawling campus of a military school about 15 miles northwest of Baltimore’s harbor. At first glance, the McDonogh School wasn’t an obvious place for two of the nation’s top astronauts to train for the final mission of Project Gemini. But Lovell and Aldrin came seeking the answer to a pressing question: “How about under water?”

Earlier that year, in June, Eugene A. Cernan pressurized his spacesuit and exited the Gemini IX capsule on the second extra vehicular activity (EVA) in NASA’s history. Cernan, who trained extensively for the spacewalk, struggled almost immediately. His spacesuit became rigid in the vacuum of space. Plans called for him to strap himself into an Astronaut Maneuvering Unit backpack, but the process was so arduous his heart rate eventually hit 180 beats per minute and his visor completely fogged over, leaving him unable to see. By the time Cernan struggled back into the capsule more than 2 hours later, his boots were filled with water. He lost 13 pounds during the mission.

Any thought that Cernan’s experiences were unique to him were dispelled during Gemini X, when Michael Collins struggled during an EVA that was cut short, and again on Gemini XI, when Dick Gordon overheated and became exhausted, struggling to complete in 30 minutes a task that had taken less than a minute during training.

Astronauts James A. Lovell, Jr. (right), command pilot, and Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., pilot.

Photo credit: NASA

“…All of us forgot about one of Newton’s Third Laws of Motion: to every action there’s an equal and [opposite] reaction,” Lovell recalled, in an oral history. “Consequently, when they went to touch the spacecraft, the spacecraft repelled them. You don’t see that on Earth, but you sure see that up in space in the zero-gravity atmosphere when you have a big mass like the spacecraft.”

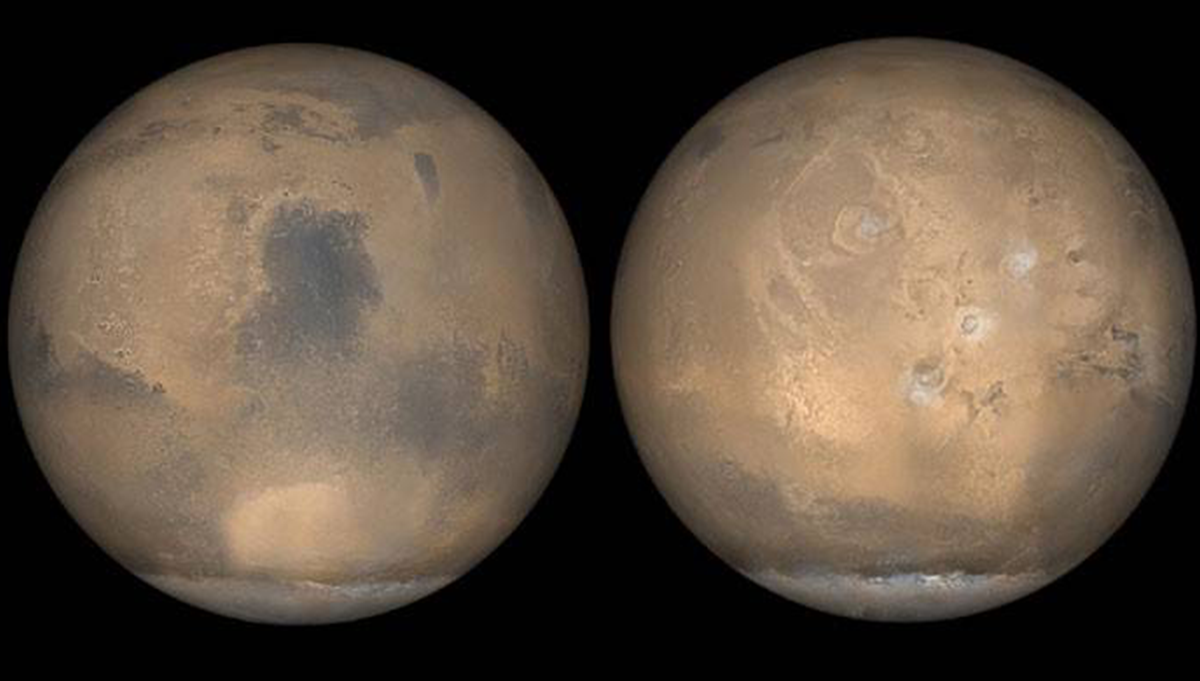

Astronaut Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr. prepares to take a rest position during underwater zero-gravity training. His feet are secured to a mock-up of the adapter section of the spacecraft by a special foot plate.

Photo Credit: NASA

“And it just so happened that someone, I don’t know who it was, said, ‘Well, how about under water? Wouldn’t that give you sort of an idea of zero gravity if we can make the astronaut neutrally buoyant? And a spacesuit will work just as well under water as it will in space,’” Lovell recalled.

Several neutral buoyancy experiments were already under way, including efforts by NASA’s Langley Research Center, which was working with a small company in Baltimore that rented the swimming pool of the McDonogh School while developing a space station airlock in a neutral buoyancy environment.

And so, Lovell, Aldrin, and a team from NASA arrived at the McDonogh School with basic mockups of the Gemini XII equipment to practice Aldrin’s spacewalks in the pool.

“We put Buzz in a spacesuit, got him in the water, made him neutrally buoyant. I had communication with him, and I sat on the side of the pool as if I was inside a spacecraft and we went through some of the basics—we had a crude mockup in the water itself—learning about working in space. Learning about the proper handholds and the proper toeholds to make sure that everything would work,” Lovell said.

On November 11, 1966, 57 years ago this month, Lovell and Aldrin walked toward Launch Complex 19 at Cape Canaveral for the more than 10-story elevator ride to the top of the Titan II rocket that would carry them into space. On the back of Lovell’s bright white space suit was a sign with “The” in bold, red letters. Aldrin was close behind him. The sign on his back read “End”. NASA strapped the astronauts into the tight cockpit of the Gemini spacecraft for the last mission of Project Gemini.

Gemini XII launched at 3:46 p.m., 90 minutes after NASA launched a Gemini Agena Target Vehicle (GATV). Lovell and Aldrin docked manually with the GATV on the third orbit and performed a series of maneuvers to align with the total eclipse over South America, which they photographed.

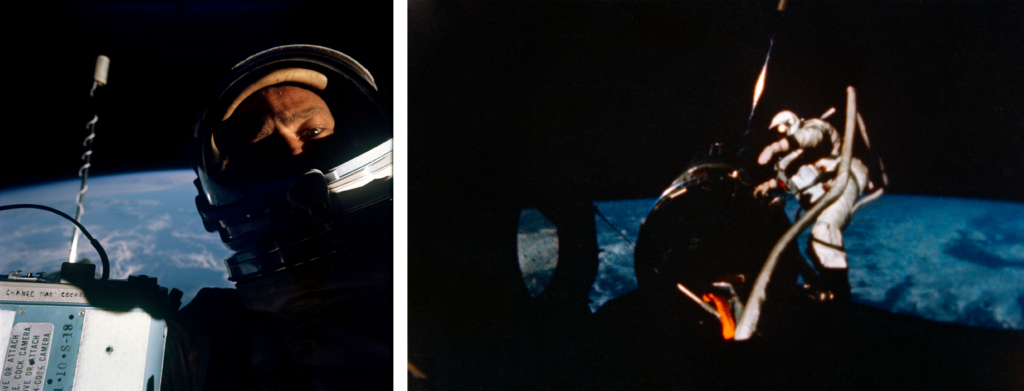

Astronaut Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., pilot of Gemini XII, is photographed during an EVA with pilot’s hatch of the spacecraft open (left) and during an EVA later in the mission, when Aldrin left the Gemini capsule and worked at the Gemini Agena Target Vehicle that Gemini XII docked with on the mission’s third orbit.

Photo Credit: NASA

The mission is remembered for the stunning success of Aldrin’s three EVAs, in which he performed dozens of precision activities, including moving to the front of the capsule to mount a movie camera to the spacecraft’s nose, taking photographs of space with an ultraviolet camera, manipulating nuts and bolts, and experimenting with waist tethers and handrails. Aldrin’s pioneering training in the pool at the McDonogh School had paid off handsomely. Neutral buoyancy astronaut training became a staple at NASA.

Gemini XII splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean on November 15, 1966, the return to Earth automatically controlled by computer. Lovell and Aldrin were picked up by helicopter and taken aboard the U.S.S. Wasp. NASA’s attention turned fully to Apollo.

“It was a major turning point in the ability to work outside a spacecraft,” Lovell recalled. “I mean, new ideas. That was the whole idea of NASA. New ideas. What can we do differently? How can we do this? And there were a lot of mistakes. There were a lot of blind alleys we went up to. Perseverance, though, was predominant in the program at the time. ‘Let’s keep on trying.’”