By John Newcomb

Probably one of the toughest, most gut-wrenching decisions I have ever witnessed on a project was the one involving the end-to-end test for the Viking lander. At this point on the project, I was trajectory analysis and design manager on Viking, so mine was not a small stake in the decision.

The traditional approach is to test an integrated system such as the lander or a spacecraft once it’s been assembled. It is a complete system test, and in general it’s the way to go. But “in general” doesn’t apply to every project. In almost every case, and certainly in our case, there are limits on your ability to simulate the total set of conditions such that the test will be 100% valid. Plus, when we got down to that point, we were running tight on time and money — and end-to-end systems tests are always expensive.

As a project progresses, an effective project team will develop and maintain a list of possible cost offsets that can reduce scope. The Viking project had developed and maintained such a list, which included some fifty items of cost or schedule offsets, along with an assessment of their associated risks. We knew it was time to turn to the list again when the NASA administrator sent word to us in 1974 (one year prior to launch) that Viking had to solve all future problems without requesting additional funding.

To test or not to test

As the time for the end-to-end test came near, Jim Martin, the Viking project manager, called us all into a meeting. Jim listened to all the arguments, pro and con, about the value of the test. The project team presented data on the smaller tests already being conducted, which had verified the performance of various subsystems and interfaces. Then we discussed the known deficiencies of the end-to-end test, as well as the risks associated with canceling it.

After Jim assured himself that every subsystem and component involved had been adequately tested, he announced his decision to cancel the end-to-end test. It wasn’t an easy decision; some of the people Jim trusted most didn’t agree with him. One of them was Israel Taback, (affectionately known by all of us as Is) chief engineer for Viking and just the best systems engineer I have ever known in my life. That was the only time during the course of the Viking mission that I ever saw is Taback put his body across the track — and Jim Martin ran over it.

Taback stood up and argued that we couldn’t afford not to run the test. Jim Martin relied heavily on Taback and had the utmost respect for him. But Martin also was a guy who had the guts to stand alone and make a decision.

Testing my own commitment

The day that Jim decided to cancel the test, I made the mistake of walking out of the meeting beside Taback. He turned to me and said, “Well, you know we’ve canceled the test.”

I nodded — and that’s when he picked me up, figuratively, by the scuff of my shirt. “As of now,” he told me, “I hold you personally responsible that there won’t be a sign reversal in the control logic for the lander.”

Taback had reason to be worried, because we had crashed — not us, but NASA — a spacecraft before due to control logic sign reversal. This was part of my responsibility on the project, and so in other words he was saying my career was on the line. I had a fellow emulating the control logic. The end-to-end test would have verified that there was no sign reversal. Now, we wouldn’t have that assurance; so, you can bet that my first stop after the meeting was in the office of the lead for the guidance, control, and sequencing computer.

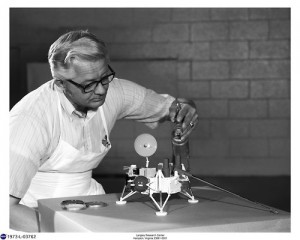

A scale model demonstrates the Viking lander’s deployed legs and radar in their post-touchdown configurations

Taback’s response — something that has been born out over the years — was that one test was worth a thousand opinions. He was a strong believer of “test as you fly, and fly as you test.” We (NASA) had screwed up several spacecraft because we didn’t obey that very simple rule. His position was that there is no reason compelling enough to delete an overall systems test. “I don’t care what you guys tell me,” I remember him saying. “There is no justification.”

But Jim did justify it.

The art of persuasion

With all this at stake, it would be easy to second-guess Jim’s decision, but there was more to the story, of course. At best, we had hoped to run an overall systems test on the lander that would be ninety-something percent valid. To do that, we’d have to fudge a few things. So, it wouldn’t have been a perfect test, number one. Number two, we were able to do a tremendous amount of testing on the various subsystem levels such that we had a lot of confidence that the system, as a whole, would work.

In most of our projects we have to make very difficult decisions with limited knowledge. I like the way one of our Viking team members, Tom Young, put it. Tom’s take on a tough decision was to say: “If we make this decision, are we prepared to defend it in Congressional testimony?” If the answer is yes, then you probably made the right decision. On Viking, we very nearly got the chance to find out.

After Jim canceled the test, we received a scathing report from the Inspector General’s (IG) office that said Viking had been placed in severe jeopardy because the end-to-end systems test had been called off, and they felt it was a totally inappropriate thing for management to do. When the IG does something like that, they give you a draft report, and they give you a chance to respond to it before it becomes official.

Jim took a look at the report and didn’t agree with the conclusions. There were no new findings about the risk of canceling the test; it came down to a difference in judgment.

| What’s in a test? The end-to-end test would verify the complex sequence of events from lander separation to landing. Due to the large distances involved and the significant delay time in sending a command and receiving verification, the lander needed to operate autonomously after it separated from the orbiter. It had to sense conditions, make decisions, and act accordingly. We were flying into a relatively unknown set of conditions — a Martian atmosphere of unknown pressure, density, and constituency to land on a surface of unknown altitude, and one which had an unknown bearing strength.In order to touch down safely on Mars the lander had to orient itself for descent and entry, modulate itself to maintain proper lift, pop a parachute, jettison its aeroshell, deploy landing legs and radar, ignite a terminal descent engine, and fly a given trajectory to the surface. Once on the surface, it would determine its orientation, raise the high-gain antenna, perform a sweep to locate Earth, and begin transmitting information. It was this complicated, autonomous sequence that the end-to-end test was to simulate. |

Jim knew that a negative report would distract our team from the work we needed to do. To address the report, he called in his deputy project manager, Gus Guastaferro, and asked him, “Gus, will you handle this?” You should understand that Gus was known for his creative negotiation techniques.

On the day of the meeting with the IG group, Gus went into the room, and shook hands with everyone. They were all young, all about 25 to 30 years old. Gus smiled, and started talking.

He said, “Oh, that’s a very interesting report you’ve got here. We have been very interested reading it. But let me ask, just to help me here, what are your backgrounds?”

He looked at the first guy, who told Gus he was a business major in college. He went to the next guy. He had an engineering background, but little practical experience. And so on.

When they’d gone around the room, Gus said, “Okay, you gentlemen have written this report and stated your opinion. You certainly have a right to do that; but you’ve just got to realize that your opinion, which is based on a total of about thirty years of minimal technical experience, has to be judged against the opinion of about 800 years of engineering experience of more than fifty senior engineers.”

He went on to say, “If you do pursue this, of course, we will request a Congressional review, and I hope you realize that you will be asking your bosses to defend your thirty years of judgment against our 800 years. Some people, I dare say, might question that kind of disparity.”

Then he left the room. (We later learned that the IG had decided not to publish the report.) That was typical Gus. Don’t get mad; just get what you need. And typical Jim, too. Know the strengths of the people working for you. Let them do the jobs they do best — like handing over the report to Gus. But also be willing to overrule them, when the overall good of the project demands it.

Jim also believed in making decisions in a completely open fashion, with everyone who wanted a say involved. And that included his critics — although he was not about to let his critics go unanswered. Jim didn’t ignore criticism; he evaluated it.

Moreover, he expected nothing less than absolute truth from his people. The one unforgivable sin was to put a spin on something or to hold back needed information. I saw people attempt to do this in a staff meeting and that was their last meeting. They were off the project that day.

All discussions of major decisions were held in open forum. The decisions were completely open and the reasons and results were made known to the entire project and to NASA management. Jim’s requirement for open communication within and outside of the project permeated the Viking project community. In that vein, the decision and the reasons for the end-to-end test cancellation were immediately made known to the Center Director, the Associate Administrator, and the NASA Administrator. They also knew that it would save $1.1 million of additional funds, and they knew the risks associated with it.

And in the end…

After that famous decision, we used to say that we were still going to perform the lander end-to-end test — it would just happen on Mars. When this “test” finally took place on July 20, 1976, and the first pictures started coming back, I don’t believe there was a dry eye in that whole Space Flight Operations Facility.

Lessons

- Truly good decisions can only be made when there is free and open communication and information exchange throughout the project.

- Team members are more likely to accept decisions, even if they do not agree with them, when they understand why and how decisions are made.

- After discussing controversial issues with team members, project managers must have the courage to make unpopular decisions, if necessary — and to take responsibility for those decisions.

Question

Why is it more difficult today to rely on expertise and knowledge when exercising judgment that challenges accepted norms?

Search by lesson to find more on:

- Testing