By Toshifumi Mukai

The hope in international projects is that one plus one will equal three—that the diverse resources, skills, and technologies of the partners will add up to more than the sum of their parts.

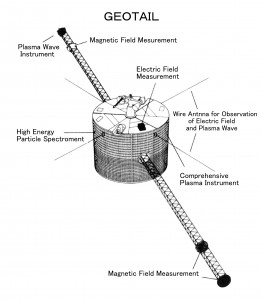

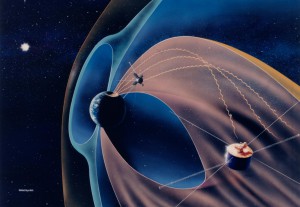

The Akebono (EXOS-D) and Geotail missions observe Earth’s magnetic field.

Image Credit: Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency

To get those benefits, however, project teams need to successfully manage the challenges that arise when different countries with different languages and cultures collaborate on a complex project. Successful project management always involves effective communication and negotiation to coordinate the activities of various groups to achieve the shared goal. This coordination is all the more challenging when the groups work in countries halfway around the globe from each other and must overcome potential cultural and linguistic barriers.

One successful international project I worked on was Geotail, a joint effort of the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS), which is part of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and NASA. ISAS developed the spacecraft and about two-thirds of the science instruments while NASA provided the launch vehicle, about one-third of the science instruments, and tracking support.

Geotail was designed to study the structure and dynamics of the Earth’s magnetotail, the part of the magnetosphere pushed away from the sun by the solar wind of charged particles. To explore this vast tail region, the Geotail spacecraft traveled in a highly elliptical orbit ranging from 8 to 210 earth radii. Its measurements of plasma and electric and magnetic fields have contributed to the understanding of the physics of interactions between Earth and the sun, and have made it a valuable part of the International Solar-Terrestrial Physics program.

One reason for the project’s success is that the scientists working for the international program had a clear common goal. That is a feature of every successful science project, the necessary foundation for success. As important as that commonality is, though, it does not eliminate the potential for cross-cultural misunderstanding and confusion.

What kinds of difficulties do cross-cultural programs face? Language is the toughest one between the United States and Japan, but we also had to think about (and find common ground) in regard to our different decision-making processes and meeting styles. We also had to deal with communication across many time zones as well as funding and legal issues (including liability and ITAR, the International Traffic in Arms Regulations that limit access to some American technology and knowledge).

English was the official language of the project. (One of my American friends said there are only two languages in the world, English and FORTRAN.) But only a few of the Japanese members spoke English fluently, and we faced many misunderstandings and much confusion during our discussions.

English and Japanese are very different not only in their vocabularies but in their structures, differences that reflect dissimilar values and ways of thinking. For example, look at the English sentence, “I am not supporting this idea,” and its Japanese equivalent:

The various elements of the statement appear in a very different order in the two languages. Notice that the negation is located at the very end of the Japanese sentence—something that may reflect a cultural reluctance to express a negative opinion in Japan. The language differences are not just a matter of vocabulary. They extend to how language and—to a certain extent—how thinking are structured.

The most important first step toward resolving this and other cultural issues is to recognize that the differences exist and to respect each other’s cultures and traditions. In the case of the language problem, both groups recognized the likelihood of misunderstanding and took steps to minimize it that included repeating and paraphrasing, slowing down the conversation, and frequently confirming that the discussion was being understood by all parties. Some American participants took Japanese lessons, which was important in several ways:

- It showed their respect for the Japanese language and culture.

- Trying to learn Japanese made clear to the Americans how challenging it is for the Japanese to work in English.

- Even a rudimentary understanding of Japanese helped the Americans understand some of the likely sources and types of misunderstandings the language differences could cause.

One of the Geotail principal investigators, Roger Anderson from the University of Iowa, has identified these language lessons as one of the reasons for the team’s successful collaboration. He also noted that the Japanese practice of seeking consensus is quite different from American and European ways of working and points to other important lessons from the Geotail experience:

- In international cooperation it is important that one side not dictate requirements to the other side.

- Diplomacy is very important. It is much better to guide your colleagues in the direction you want them to go than to make demands.

A Delta II rocket carrying the Geotail spacecraft lifts off at Launch Complex 17, Kennedy Space Center.

Photo Credit: NASA

Dr. Anderson and Dr. Mario Acuna of NASA also have called Geotail an “outstanding success” and commented that “the development of a mutual trust relationship between the partners was perhaps the most critical element of all for success.”

Mutual respect, trust, and recognition that cultural differences exist, matter, and must be explicitly dealt with are requirements of successful international projects. In summary, I would suggest these principles for the success of international collaboration:

- Two (or more) teams share the same goal and seek the overall optimal result, not the local optimum.

- Each team should clearly recognize and value the other party’s different culture and traditions.

- The single most important word in international projects is trust. Team members earn trust by being sincere, honest, and open-minded.

These principles apply especially to international projects but no doubt the same principles contribute to the success of any challenging project in which team members work for different organizations or in different locations.

About the Author

|

Toshifumi Mukai is senior chief engineer at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. |