By Katrina Pugh and Jo Ann Endo

“Jamming” is an effective technique for sharing organizational knowledge.

What do you do when you have valuable knowledge spread among multiple people in multiple organizations, and they don’t consider themselves experts?  Here’s an example of just that: a number of quality-improvement teams working for health-care providers around the country with some remarkable successes and some failures, but few seeing what we call the “wider view”—the cause and effect of their teams’ success.

Here’s an example of just that: a number of quality-improvement teams working for health-care providers around the country with some remarkable successes and some failures, but few seeing what we call the “wider view”—the cause and effect of their teams’ success.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), a not-for-profit organization dedicated to fostering improvements in health-care delivery throughout the world, saw the imperative of knowing what made health-care quality-improvement teams successful. Spreading the knowledge could mean the difference between life and death for patients.

One of IHI’s most far-reaching efforts is their IMPACT Communities. Made up of hospital teams from around the United States, these distributed communities use IHI’s tools and methods to introduce quality-improvement initiatives. IMPACT Communities have dealt with important issues, including health-care-associated infections and improving care in emergency departments and clinical office practices, resulting in improvements that have saved millions of dollars annually. In 2009, the multi-hospital “Perinatal” IMPACT Community of about one hundred doctors, nurses, technicians, administrators, and project managers had been working with IHI for two years to reduce medical errors, using IHI’s process-improvement methods in maternity wards. IHI knew that they would be launching future improvement communities in other care areas and believed that those communities could learn a great deal from this group.

Hidden Know-How

During planning discussions, IHI leadership felt there were some remarkable cases of hospital teams quickly coming together to do effective work while other teams took longer to form, agree on goals, establish effective communication, and become productive—if they ever did. They wanted answers to these questions:

- How do hospitals become ready to consistently adapt IHI’s practices?

- How do diverse hospital quality-improvement team members “gel” into a team that is a force of change within their organizations?

IHI needed a process that could capture what people knew intuitively (and collaboratively) but wasn’t written down. And IHI needed to incorporate their knowledge into new processes rapidly. If there were efficiencies to be had and lives to be saved, there wasn’t a moment to spare.

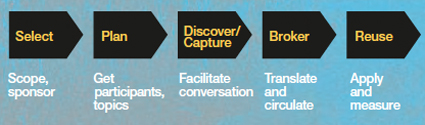

Enter Knowledge Jam. Knowledge Jam is a process for bringing out the tacit knowledge of teams and experts through a formal process of targeting specific knowledge, facilitating a knowledge conversation between experts or veteran teams (knowledge originators) and knowledge seekers (or their representatives, the “brokers”), and then ensuring the knowledge is put into practice. Knowledge Jam’s steps are select, plan, discover/capture, broker, and reuse. The Knowledge Jam cycle extends from targeting what (and whose) know-how is needed to eliciting it, translating it, reusing it, and measuring its impact.

Consultants Katrina Pugh, Align Consulting, and Nancy Dixon, Common Knowledge Associates, facilitated a Knowledge Jam with IHI in the spring of 2009. Knowledge originators were seven health-care practitioners (nurses, doctors, administrators, and project managers) from six hospitals. Brokers from IHI included IHI staff Jo Ann Endo, Sarah Jackson, Jonathan Small, and Kiette Tucker and IHI faculty Marie Schall and Ginna Crowe, who also occasionally doubled as originators.

Efficiency is a critical part of a Knowledge Jam. The actual discover/capture event, which involves originators and brokers, generally lasts only 90 minutes. Rigorous planning and ongoing, purposeful interactions between brokers and originators, brokers and brokers, and originators and originators save meeting time for everyone. The event is more about “channeling insight to a target” than the “harvesting in bulk” and dumping into an all-too-often stagnant repository that characterize some knowledge management efforts.

Another key to Knowledge Jam efficiency is the three disciplines of facilitation, conversation, and translation. These are threaded into the Knowledge Jam’s five-step cycle:

Facilitation

A facilitator helps select, plan, and coordinate the Knowledge Jam process, organizing the early structuring of concepts, providing quality control, aligning Jams to business objectives, and, most importantly, setting a tone of curiosity and respect for the Jam that fuels conversation that yields unique and reusable insight. Facilitators model and reward respectful, open inquiry and discourage defensive, criticizing, or protective attitudes. During the four planning months, we identified topics and participants, held a planning meeting, and prepared for the discover/capture event. We also conducted approximately ten interviews with brokers and originators. Participants in the planning included nurses, doctors, quality-program managers, IHI faculty and staff, and program designers. (Note that none of this was full time; Knowledge Jams have a surprisingly light time footprint.)

Conversation

Knowledge Jams invite the curiosity of those who will use (or transmit) the knowledge. An open conversation between the brokers and originators surfaces the conditions around the facts (How did you decide to do that?). The Jam can also reveal connections between events, outcomes, and people that we hadn’t considered. Drawing out context in this manner makes captured know-how reusable in other contexts.

Three dimensions of effective conversation are the “posture of openness,” “pursuit of diversity,” and “practices of dialogue.” The diversity dimension deserves some emphasis, as it played a key role in drawing out valuable context during the discover/capture step in the IHI Knowledge Jam. The group was critiquing a draft definition of what it means for multidisciplinary hospital quality teams to “gel” as they come together to implement improvement practices.

Knowledge Jam Comments |

Summary/Implications |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Add to “gel” definition: | ||||

| Facilitator: What would you add to or take away from this description of what team “gelling” is? | ||||

| Originator 1 (Nurse, New Hampshire Hospital): Open communication is a big piece of it. There needs to be a process to work through disagreement. By “open communication” I mean safety in the group to say what you think. | Communicating openly | |||

| Originator 2 (Nurse, Connecticut Hospital): Taking the appropriate steps (intervention) to get the results. Having agreement about what those interventions will be. | Working for multidisciplinary agreement on interventions | |||

| Broker 1 (IHI staff, Statistician): A team may gel before it actually has results. | ||||

| Originator 1:A willingness to hold each other accountable for each piece of the project. That includes committing to having that hard discussion about desired results, and ensuring that you are getting those results out of the process. | Holding each other accountable | |||

| Broker 2 (IHI faculty, Psychologist): For me, what we are describing is a “functional team.” There needs to be a relationship factor, beyond just our functional needs. | Having relationships at human, not just task, level | |||

| Facilitator: Please, can you elaborate? | ||||

| Broker 2: You need to know people as humans, and not just be task-oriented. That means developing a relationship that has to do with our personal space—for example, what we are working on. It means acknowledging that life gets in the way. To me, that makes it a more sustainable team. | ||||

| Originator 3 (Nurse, Louisiana Hospital): A mutual respect within your team. | Respecting each individual’s role in the program | |||

| Facilitator: How is this different from the personal getting-to-know-you? | ||||

| Originator 3: If I am working in a multidimensional team, there is more than just “respect.” What I mean is, “knowing what each other is doing.” For example, [implementing a change] means step AJ for nurses, and for physicians that means Y. So when we meet collaboratively we are taking the time to see what the implications are for each area. | Knowing more about each others’ tasks and what it takes to get the job done | |||

| Originator 2 (commenting at the end of the discover/ capture event): We all have the same goals, but it is interesting that the way we meet them may differ. It has to do with culture, structure, and management styles of the organization. Maybe it’s the styles of people who have quality-improvement roles, who bring their uniqueness to the table. | ||||

The nurses, doctors, and IHI staff contributed a spectrum of ideas to the definition of “gelling,” including communicating, having mutual respect, recognizing each team member’s work and life burdens, building relationships, and accomplishing measurable quality-improvement goals together. They also made clear that a team can gel before it has results. The participants’ expanded definition helped make their subsequent recommendations far more useful, decisive, and prescriptive.

Translation

Involvement by brokers throughout the Jam gives them a sense of ownership. They remix the ideas into their context (their division, country, project, or product) and integrate those ideas for action. The translation of the knowledge into a project template, a design spec, or a marketing protocol suits the knowledge seekers who are embarking on a decision, innovation, process revision, or outreach program. Brokers often use change management strategies and collaboration or social media technology like team sites, wikis, and microblogs to ensure jammed knowledge gets communicated, amplified, and used.

The three disciplines make jamming more efficient, but they also extend to more strategic forms of knowledge transfer. For example, the culture of facilitation (intention), conversation (openness), and translation (stewardship) is just as applicable to communicating, socializing, and adopting a new business model as it is for remixing an expert’s or team’s know-how for a tactical program.

A Big Insight

Effective perinatal community teams revealed that it is critical to gel intentionally (say, by adopting new methods and metrics) but that informal interactions, such as holding check-ins and telling stories, help them stick together. The group came to agree on the following dimensions of gelling:

- Conduct goal setting as team building.

- During the relationship-building process, meet with peer organizations with experience in similar health-care improvement methods.

- Infuse shared decision-making with a diversity of experience and values.

- Build cohesiveness through both performance data and storytelling.

- Integrate new members intentionally.

- Formally sustain the organization’s commitment to the new health-care improvement culture through project management and work structures.

As a consequence of the Knowledge Jam, IHI added these gelling components to an organization-wide design model called the “Results Driver Diagram.” The diagram is a critical part of the development of all IHI’s collaborative programming, affecting hundreds of health-care organizations around the United States.

Starting Your Own Knowledge Jams

Taking Knowledge Jams into your organization requires thinking ahead to where the tacit knowledge of experts and teams could potentially improve processes, accelerate innovation, or expand margins. Next is prioritizing topics with potential originators and brokers. Then let the jamming begin! Good facilitators can set the tone, encourage brokeroriginator conversations, and manage the whole process through epiphanies and low points alike.

Because the application of the knowledge (and the corresponding choice of knowledge to jam) are targeted and collaborative, Knowledge Jams’ outcomes can be substantially more cost- and effort-efficient than traditional means of knowledge transfer. IHI was able to capitalize on newfound gelling insights just at the moment they were preparing to launch new IMPACT Communities. So, too, might you find that a Knowledge Jam could inform your critical program with the hidden know-how of those brilliant, but time-starved, experts and veteran teams.

About the Authors

|

Katrina Pugh is president of Align Consulting and author of the forthcoming book, Sharing Hidden Know-How: How Managers Solve Thorny Problems with the Knowledge Jam (Jossey-Bass, 2011). | |

| Jo Ann Endo is the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s (www.ihi.org) communications specialist and administrator of the Mentor Hospital Network. She has worked at IHI since 2005, focusing first on the 100,000 Lives and 5 Million Lives campaigns and now on the IHI Improvement Map |

More Articles by Katrina Pugh

- Harvesting Project Knowledge (ASK 30)