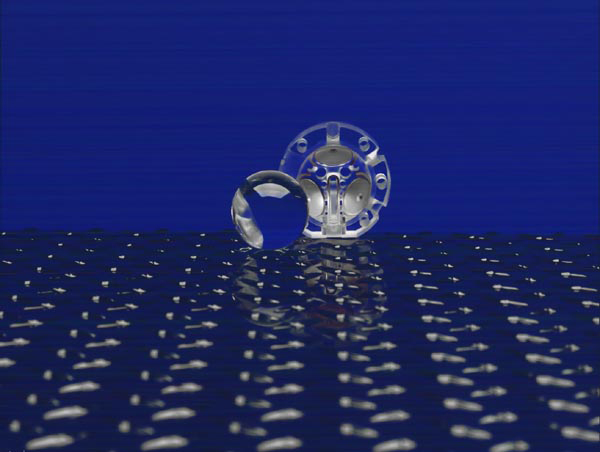

Monument at Complex 14 for the Friendship 7 mission flown by John Glenn, Jr., on February 20, 1962. Image courtesy of Jen Scheer.

November 29, 2011 Vol. 4, Issue 9

Jen Scheer had a great idea to restore Cape Canaveral Air Force Stations Launch Complex 14. But sometimes having the great idea just isnt enough.

Monument at Complex 14 for the Friendship 7 mission flown by John Glenn, Jr., on February 20, 1962.

Image courtesy of Jen Scheer.

Mercury Falling

Nearly two years ago, Jen Scheer, former Space Shuttle Program technician, toured the launch complexes at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, adjacent to Kennedy Space Center (KSC). She visited a number of sites, but one in particular stuck in her mind. The site was Launch Complex 14, best known as the place where John Glenn lifted off in his Mercury capsule, Friendship 7, to become the first American to orbit the Earth in 1962. The decomposition of the complex over time was apparent. “It was sad to see it in this state,” she said. “It didn’t seem to be a fitting tribute to what was accomplished there.”

Scheer left thinking about the complex. Wouldn’t it be cool to do something with the site? Not a huge fan of just erecting monuments, Scheer wanted to find a way to make the complex come alive—to make it a trip back in time, an educational experience relevant to today’s space exploration industry. She thought about the retirement of shuttle, the kids sitting in classrooms, the workforce that would be lost, and the knowledge and know-how that would be lost. “I was worried that when we’ll need it, it won’t be there anymore,” she said.

And then an idea came to her, one that would create jobs, educate kids, and inspire the next generation of explorers.

Mercury Rising

She called it “Project Mercury Rising.”

The idea was to restore Complex 14 to look like it did in the height of the Mercury program and stand up an educational program there designed to teach teens the engineering and hands-on technical skills needed for space flight. Participants would master the basics using Mercury replica hardware, then move on to small modern payloads- which would be launched by a partner organization. On paper, it made perfect sense. The program would employ members of the shuttle workforce about to be laid off, facilitate the transfer of valuable technical skills and knowledge, and engage kids in hands-on learning in the context of a historic program.

“You’re honoring what happened there at that site,” said Scheer. “It worked on so many different levels; I thought it would be perfect.”

Aerial view of Launch Complex 14 with Missile Row visible to the right. Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9), visible on Pad 14, is scheduled to carry astronaut Gordon Cooper for the fourth manned orbital mission.

Photo Credit: NASA

Scheer did what many people do when gripped by a good idea: she spread it. She talked to anyone who would listen: industry leaders, politicians, astronauts, teachers, people at NASA, people outside of NASA. They all told her the idea was great. The interest and enthusiasm were there. However, Scheer quickly had an important realization. “Everybody loved the idea,” she said, “But just loving the idea isn’t enough.”

Activation Energy

Scheer knew that realizing her idea would come with many challenges. She knew what she had: an idea, enthusiasm, and interest. She also knew what she needed: access, permission, partners, a team, funding, and most of all, a business plan to tie it all together.

“The site itself is a bit of a challenge,” she said. “It isn’t just a place for people to come to and play.” She needed to sort out permission to the site.

She honed her skills of persuasion and started to build up healthy alliances with people onsite and off. Perhaps, she thought, Space Camp would see value in it. With the retirement of the shuttle, the program might be looking for something new. Perhaps she could partner with technical training programs or the local and state government. Kids could go through the program and walk out with a marketable skill. “You’d have to show value to the parents,” Scheer said. She envisioned different tracks, including technical, engineering, life sciences, and even science journalism.

People expressed interest in becoming part of a team. “Lots of people wanted to help, but you’ve got to have things to give them to do,” she said. However, the project was so early in its life cycle that it was difficult to assign specific tasks to anyone.

She even had the promise of funding from partners, but she needed a business plan. One organization recommended that Scheer seek the help of the local small business development center. She heeded their advice and attended a course there on business planning. “It didn’t pertain to what I was trying to do whatsoever,” she said, noting that it focused on businesses making widgets or opening up a restaurant. Scheer’s project was different, and she didn’t have the business plan to tame it.

“The whole thing stalled out at the business plan. You need the business plan to get the money,” explained Scheer. “Nobody is going to give you money without a business plan and this is where I really needed help.”

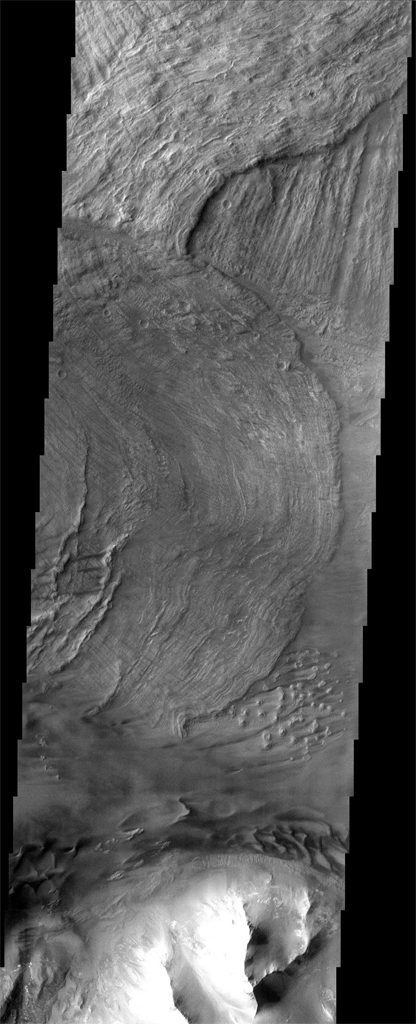

Recent image of Complex 14 at Kennedy Space Center.

Image courtesy of Jen Scheer.

Mercury Idle

Scheer left the shuttle program in 2010. Even out of work, Scheer was busy to the point of having no free time. She was writing a book, taking photographs of KSC every morning, volunteering at a local space museum, visiting classrooms virtually through Skype interviews, and managing the Space Tweep Society,

to name a few. Her skill set brought her numerous other opportunities as well, so many that she kept a folder in her email titled OPP: “Other Peoples’ Projects” to keep track of all of the projects others wanted her to contribute to.

She had yet to harness the power that sets seasoned project managers apart: the ability to say no. Because she was doing so many things, Project Mercury Rising started to idle. “When you’re trying to work on something and are constantly bombarded with other proposals, the project suffers” she said.

Maybe One Day

Interest in the project is still alive and well. “I’ve even had a lot of adults tell me that they want to go to this camp,” laughed Scheer. “It should happen,” she said, “whether it’s me that does it, or some corporation that decides that it’s a good idea and wants to do it.” She has never been possessive of the idea. “I don’t mind if somebody else takes the idea and runs with it.”

Project Mercury Rising is an example of how a good idea alone is not enough. Effective management, networking, fundraising, and communication skills are all vital to launch a unique project that doesn’t fit an existing business model. Opportunities for young professionals to develop these capabilities are not always easy to find. “A mentor in the space industry with knowledge of business planning would have been invaluable,” Scheer said. “It would have made all the difference in the world.”