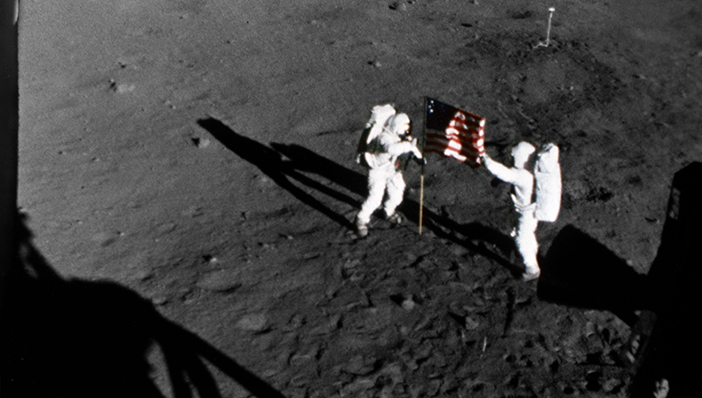

The United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy rocket, with NASA’s Orion spacecraft mounted atop, lifts off from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station's Space Launch Complex 37 at at 7:05 a.m. EST, Friday, Dec. 5, 2014, in Florida. The Orion spacecraft will orbit Earth twice, reaching an altitude of approximately 3,600 miles above Earth before landing in the Pacific Ocean. No one is aboard Orion for this flight test, but the spacecraft is designed to allow us to journey to destinations never before visited by humans, including an asteroid and Mars.

Photo Credit: NASA

This month, Esquire—the octogenarian magazine that has spent much of its years reporting on the bar, bedroom, and bathroom—describes a near disaster on the International Space Station (ISS).

…the toilet’s lights flashed red instead of green. (Scott Kelly) removed a panel and discovered a pretreat leak… It formed a shimmering sphere of acids the size and color of a cannonball that now floated… He grabbed an old T-shirt to soak up the pretreat… Unfortunately, that old T-shirt had sweat and therefore water molecules trapped in its fibers… That old T-shirt didn’t act like a sponge. It was flint. Now Kelly saw and smelled smoke.

The article by Chris Jones makes short work of describing the incendiary science of water and acids entertaining for two more paragraphs, concluding this near death-by-toilet occurrence with ISS crewmate and chemist, Cady Coleman, using a big bag filled with wet towels and limited oxygen to snuff out the smoldering threat. Though Cady’s soles were most likely floating, she had thought on her feet. By retelling this story, we begin to finesse a best practice for putting out a fire in low orbit by using the right amount of water and by exhausting the source of oxygen by containment.

Recently, at a Project Management Institute (PMI) Project Management Office (PMO) Symposium, Harvard Business School professor and author Michael E. Porter stated in his keynote presentation: “Strategy is not about best practice; it is about choices about how to be unique. However, if we give up operational excellence then strategy doesn’t matter because we will fail.”

One must assume that Porter is defining best practice roughly here: It is a method or process that has consistently—through analysis, testing, and most importantly experience—resulted in desired outcomes and is superior—through speed, cost-efficiency, and risk-mitigation—to any other known method or process. Operational excellence relies on best practices.

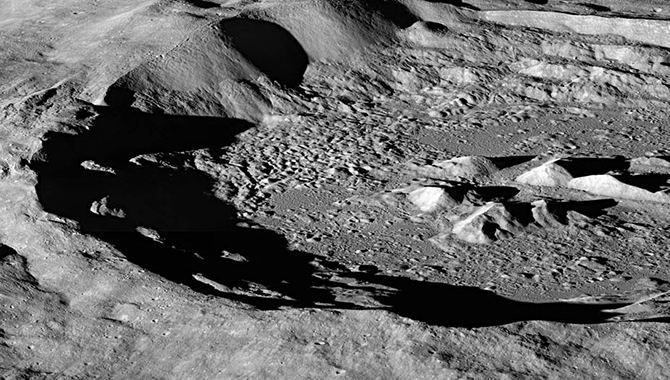

The idea of a strategy being about choices on how to be unique is a provocative notion. Strategy breaks free of the singular pull of all “tried and true” processes. A genuine “strategy” must contain at least one unique practice we choose to put into effect. Our strategy’s perceptible outcome must aim to be innovation itself. Although science is all about repeatability, it is built into the American character that we do not want to follow someone else’s exact footsteps. For long-term better or for short-term worse, we want to be first, to trek boldly where no one has, even if it has to be two steps forward and one step back.

Innovation cannot be at the expense of operational excellence. Before there is this innovation, there has to be testing as undoubtedly as there has to be analysis before testing. During a Masters with Masters interview, Nobel Prize winner and GSFC Senior Project Scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope John Mather says, “Testing is tiresome, tedious, boring, and essential. If you do not test it, it will not work. There is no such thing as risk that it will not work, it is a certainty it will not work.” This broad axiom can be scaled down (extracting the nested quadruple negatives) to Murphy’s Law: If anything can go wrong, it will. “I never believe real risk assessments,” Mather states further, “and I never believe that an analysis can really prove that things are really okay.”

With the successful Orion Flight Test this month, we are one step closer to taking humans farther than they have ever gone before. And with Scott Kelly scheduled to spend a year on the ISS—as Esquire has reported this month—we are taking another step with another foot.

Knowledge services aim to share where our footprints have been and strive to help us think on our feet while taking our best steps forward on our newest adventures.