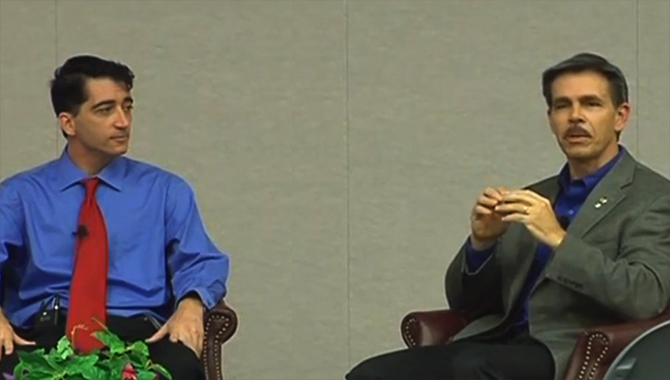

Mike Ciannilli, NASA Test Director, and Jon Cowart, NASA Commercial Crew, during the 23rd Masters with Masters in the video interview series.

Photo Credit: NASA

NASA CKO Ed Hoffman sat down with two master practitioners, with over a half century of experience between them, in this edition of Masters with Masters.

On July 24, 2014, in the newly named Armstrong Building at Kennedy Space Center (KSC), Ed Hoffman, NASA Chief Knowledge Officer (CKO), spoke with master practitioners Mike Ciannilli, NASA Test Director, and Jon Cowart, NASA Commercial Crew, during the 23rd Masters with Masters in the video interview series.

For almost two decades, Ciannilli has worked for NASA in manned spaceflight programs, including launch, landing, and recovering, and he has been regularly capturing and sharing critical knowledge on projects and mishaps. A NASA civil servant for nearly three decades, Cowart has also been involved in manned spaceflight, including space shuttle Atlantis and commercial vehicle, currently leading the development for low Earth orbit transportation with companies such as SpaceX.

With a half century of experience between them, asking this overarching question was a given: What was the most important lesson of their careers?

“I got involved in ARES I-X project,” said Cowart. “It is the embodiment of every lesson we’ve ever learned, which is: get a small team of people – smart people – give them the task, get out of their way, help them if they need it – if they ask for help.”

Ciannilli shared, “When you look back and you look through all the accident histories and read all the accident reports from Apollo through Challenger to Columbia, the same systemic things are coming through: communication breakdowns.” He stressed that communication is even more essential while building a team between contractors and the government: “There’s misunderstandings… It’s slightly different languages they speak, slightly different perspectives on how they see the world.”

Describing his work with SpaceX, Cowart mused aloud, “It’s a lot like the vibe we had at NASA back in the 60s – a bunch of young kids who aren’t fully aware of the awesomeness of what they’re doing.” He added, “SpaceX does business differently, and they are not like NASA… and they are very proud of that.” He emphasized the importance of building trust. “They have to understand that you’re not there for any other motivation other than to get the right thing done and to help them.”

Trust ultimately means honest communication. “It’s really easy to ask a question and want a certain answer,” stated Ciannilli, “but I really will listen to an answer you might not want to hear.” He underscored that communication and reflection should be built into every stage of the project. “Keep communication going.” Both he and Cowart conveyed that taking time to communicate is as important as any other activity in the schedule. “What I would love to see done,” said Cowart, “is to set out a schedule for… what I would call ‘built-in holes’ where there’s no activity. Those are times to catch up.”

Hoffman asked if another comparable practice of “pre-mortems,” when a team as a mid-cycle exercise pretends that the project has failed completely and the team asks itself what could have gone wrong to have caused the hypothetical failure. Cowart shared they did something similar on Ares I-X.

A reoccurring theme of the conversation was that of really listening beyond simply hearing. Cowart expressed this by truism: “Two monologues do not constitute a dialogue.” Cianilli stressed his truisms as knowing the audience, being receptive to feedback, and making sure that he, too, is really listening. There are breakthrough moments in communication as well as steady progressions towards understanding. What is important is the willingness to understand, to use whatever necessary tool or skill (Ciannilli referred to using another “tack” as if sailing) to cross whatever distance no matter how great.

How they first became interested in spaceflight?

With Ciannilli, it was always something he wanted to do since he could remember. Cowart, however, could point to one night, Christmas Eve of 1968, listening to astronauts Borman, Lovell, and Anders, reading from The Book of Genesis as they orbited the moon. “I’m lucky in the sense that people from my generation, we have that… going to the moon… there is an old saying, if you want to build a ship, don’t collect people to… assign them work… rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.”

View this Masters with Masters event on the APPEL YouTube channel.

To watch previous Masters with Masters videos, please visit the APPEL YouTube channel.