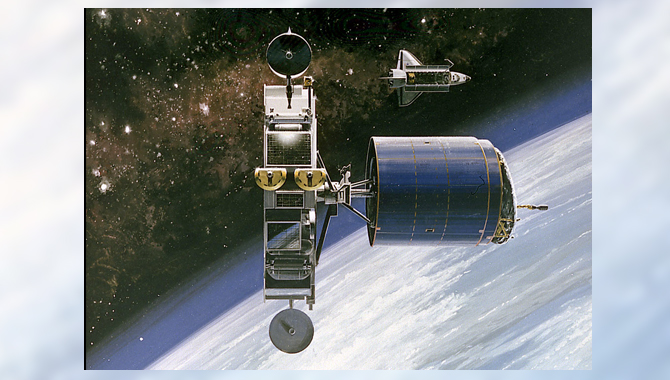

With Earth and one of the station's solar arrays as a backdrop, NASA astronaut Clayton Anderson works during the third spacewalk of the mission.

Photo Credit: NASA

When I started working at NASA in 2007, I was on top of the world.

Fresh out of college with my brand new degree, I thought I knew it all. I was a boy from a small town in West Virginia, headed to the big city of Houston to work for NASA.

My first job was in space shuttle training at Johnson Space Center. I was part of the Data Processing Systems and Navigation group responsible for teaching astronauts, flight controllers, and other instructors about the computers and software onboard the shuttle. To become an instructor, you have to go through rigorous training in your particular system and be certified by senior instructors to teach the various lessons about it.

During my certification run for my second class, the senior instructor spent much of the two-hour class asking questions. I couldn’t figure out why she didn’t know the answers already. After all, she was the senior instructor! I gave what I thought was the right answers to every question. During the debrief after the class, the instructor quickly ended the suspense about my fate with a simple “you didn’t pass.” Our conversation over the next hour changed the way I think about myself and my work, and it provoked thoughts that have helped shape me since then.

The instructor reminded me of the magnitude of our job as instructors in the space shuttle program. Lives depend on the knowledge that we teach them in these one-on-one classes. The mistake I was making was easy to fix but so hard to swallow. I had to learn how to say, “I don’t know.” This was something that I clearly was not very good at saying. I had spent most of my short life thinking that I knew the answer to most things and that I constantly needed to show my peers how smart I was. This wouldn’t fly at NASA or anywhere else for that matter. All I had at the beginning of my career was my reputation. My reputation at that point was based on the first impression that I was making with people, and how I was able to answer their questions. I didn’t want that first impression to be of a person who spouted things that he thought were right, just so he could give an answer. I quickly learned how powerful being able to say “I don’t know” was and how to follow up with folks once I found the correct answer.

One example: In 2010, the crew of STS-131 was in quarantine prior to launch when one of them called me with a question that came up as they were reviewing their flight data files: he wanted to know the rationale for a few steps regarding reconfiguring the computers from their ascent configuration to the orbit configuration. I didn’t know the answer off the top of my head. Here was an astronaut about to go into orbit, asking something that was supposedly in my area of expertise, and I didn’t know the answer.

If I hadn’t had that earlier learning experience during my training, I might have just given him an answer that I thought was probably right. I didn’t though. I was able to say, “I don’t know, but let me find out for you.” I quickly researched the question, talking to some flight controllers, and provided the correct response within a few hours.

To this day, I often see people at NASA struggling to say, “I don’t know.” I hope that those reading this will understand the power of admitting that you don’t always have the answer and taking the time to find it. I know in some time-critical situations that we need to be able to come up with an answer quickly, but it needs to be the right answer. I hope that we understand and respect people who take a little more time to make sure that they are providing the correct information, not just giving an answer because they think it’s not acceptable to admit they don’t know everything.

Justin Smith is the Program Analyst in the Strategic Communications Office at NASA’s Independent Verification & Validation (IV&V).

Read more articles in the “My Best Mistake” series.