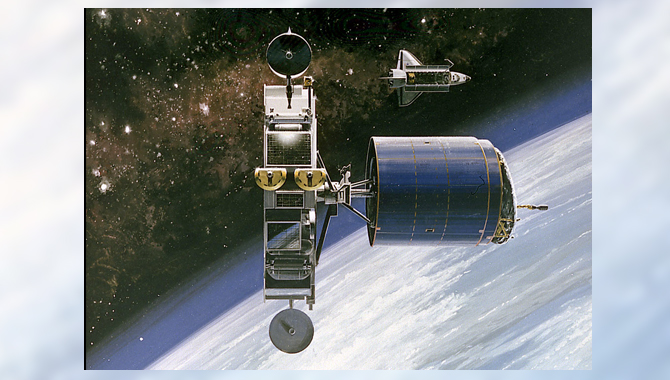

This 1986 artist's concept shows the Orbital Maneuvering Vehicle (OMV) towing a satellite. As envisioned by Marshall Space Flight Center planners, the OMV would be a remotely-controlled free-flying space tug which would place, rendezvous, dock, and retrieve orbital payloads.

Image Credit: NASA

I’m not sure that the decisions I made as operations manager of the Orbital Maneuvering Vehicle (OMV) program nearly three decades ago were necessarily mistakes, but the problems that ultimately killed the OMV were certainly real.

They taught costly but valuable lessons that I’ve applied to the rest of my career.The OMV was conceived as a space tug, a vehicle that could retrieve satellites, carry them to the shuttle for servicing, and then return them to their orbits. The vehicle was to be developed at Marshall and I was operations manager, located at Johnson. TRW won the bid with what seemed an unbelievably good deal. We were somewhat skeptical about their ability to do the work for the proposed $205 million, and our skepticism was justified when cost overruns ended the project. So the first lesson I learned was: if a deal seems too good to be true, it probably is.

The OMV was approved soon after the Challenger disaster, so the shuttle was not flying at the time. Budget cuts were taken against projects like ours, without critical schedules. The cuts delayed the project launch and completion dates. The budget cuts and delays masked other development problems that were occurring on the program. Also, schedule slips always mean added expense, which in this case contributed to OMV’s demise. The lesson I took away from this situation was to think about what you can do if you don’t get all your funding and complete what you can on time. I applied that learning to the International Space Station when the Columbia accident halted shuttle flights. We built trusses for the station even though there was no vehicle to fly them and stored them until the shuttle was flying again. That decision saved money and allowed the trusses to fly as soon as the shuttle was ready.

When we were directed to make budget cuts, the folks at Marshall removed technologies and capabilities from the OMV design to lower costs. I chose not to make cuts in the operations budget. I’m still not sure what the right thing to do was. Should you stick to your guns when cuts might save a project? (They didn’t in this case.) At what point do reduced capabilities mean the project might not be worth saving? The closest I can come to a useful learning is to say, resist defaulting down either the path of major cuts or stubborn refusal to cut at all.

The other important lesson I took away from the OMV experience is a lesson in life balance. Many NASA people are dedicated to their work; we have to be able to accomplish the challenging tasks we set ourselves. But it’s a mistake to commit so much of your life to a project that you neglect family and other aspects of your private life. As was the case with OMV, projects are sometimes cancelled despite the heroic efforts of team members. Giving too much—giving everything—to a failed project could leave you without either professional or personal satisfactions.